This week, the Obama administration announced a change to the rules governing overtime pay.

By Dwyer Gunn

Research-oriented academics are not exempt from the overtime regulation. (Photo: Mario Villafuerte/Getty Images)

Earlier this week, the Obama administration announced a significant regulatory change to the rules governing overtime pay. Beginning on December 1, most salaried workers earning less than $47,476 must be paid overtime (time-and-a-half) if they work more than 40 hours a week. The previous salary threshold, which was set back in 2004, was $23,660. The Department of Labor estimates that the new regulation will directly affect 4.2 million workers and will indirectly impact an additional 8.9 million workers. The salary threshold, which is indexed to the 40th percentile salary in the lowest-paid region of the country, will be automatically updated every three years.

The proposal, which is technically an update of the overtime protections in the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, has been in the works since 2014—as has the debate over its probable effects. Conservatives argue that the proposed changes will harm small businesses and may force employers to cut jobs or lower workers’ base pay. (The New York Times has reported that Republican lawmakers have promised to block the change.) Liberals, meanwhile, maintain that the update is a crucial step to reversing the wage stagnation that has plagued middle-class America. Jared Bernstein of the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities described the policy update in the Washington Post as “a progressive change that was a long-time coming, one that will deliver a boost in pay to some workers and relief from unpaid overwork for others.” Vice President Joe Biden told reporters that it “goes to the heart of the defining issue of our time, that is restoring and expanding access to the middle class.”

Overtime protections, much like the minimum wage, have been pretty significantly eroded in recent years due to a failure to update the salary threshold, as well as changes in the rules governing who should be exempt from overtime requirements. “It was an appropriate adjustment,” says Harry Holzer, an economist and professor at Georgetown University. “I think it will get more workers overtime pay. People making $25,000 to $50,000 a year, that’s mostly workers that are solidly in the middle.”

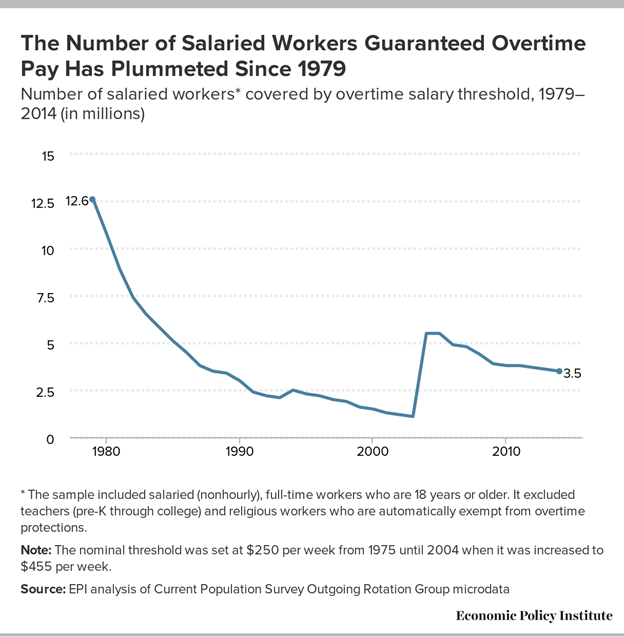

This chart, from the liberal Economic Policy Institute, illustrates how the number of salaried workers eligible for overtime has declined over time.

(Chart: Economic Policy Institute)

In 1975, 65 percent of salaried workers were guaranteed overtime; in 2013, only 11 percent were eligible for overtime protections.

The expected economic effects for workers—which the Department of Labor’s website lays out—are mixed. At the most basic level, some workers will simply be paid more for the extra hours they work. Others won’t be asked to work as many hours. Some employers may raise workers’ salaries above the threshold (so they don’t have to pay them overtime).

Most people would view these effects as positive, but there are more troubling potential consequences. Opponents of the law insist that many employers will reduce the hourly base pay of their employees but maintain overtime demands, which would leave overall compensation essentially unchanged. Perhaps more concerning: Anything that makes workers more expensive to employ might encourage employers to hire or employ fewer workers, either by outsourcing or automating jobs.

Many economists, however, believe any negative effects will be minimal. Firms can’t easily lower people’s wages to below-market levels — particularly in light of recent evidence suggesting that earnings growth might finally be starting to increase. Holzer is also skeptical that the change will have a significant effect on outsourcing or automation trends.

“The four million workers who will now get this overtime, they’re scattered across all kinds of sectors and firms,” Holzer says. “When an entire workforce is going to be twice as expensive, companies will re-evaluate. But this is a modest bump spread across a lot of different people.”

These changes to the overtime rules won’t, on their own, restore the middle class or reverse the structural effects of trade and technology on the American economy. But they’re a step in the right direction. They’re also, Holzer argues, a demonstration of what’s at stake in the coming election.

“It’s not a dramatic improvement for the middle class, but it’s not trivial either,” Holzer says. “There’s a whole bunch of areas where the government played an important regulatory role protecting workers in the labor market, and along several of those dimensions, the regulations had weakened. When you have a Democratic administration, they can do something to strengthen those regulations.”

||