The dusty border town of Namanga, between Tanzania and Kenya, was once the territory of Maasai pastoralists and is now home to 9,000 people.

By Nathan Siegel

No Man’s Land along the border between Kenya and Tanzania in the town of Namanga. (Photo: Nathan Siegel)

In Namanga, a town on the border between Kenya and Tanzania, it’s hard to know where one country stops and the other starts. While a major border station is almost finished along the main road, signaling tourists and truckers where to pass, for the rest of the population the border is almost non-existent.

In the center of town, an expanse of dirt no wider than 200 feet separates the two sides. Elsewhere, there is no indication whatsoever of the division.

When the town of now 9,000 was territory of Maasai pastoralists, who still feature prominently in Namanga, there was little, if any, border to speak of. Like in the old days, Maasai still herd their cattle across the border without any trouble. But Namanga has come a long way since then. It’s now a multicultural transit point between Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, and Arusha, Tanzania’s second largest city and a major diplomatic and tourist hub.

Yet despite being in the midst of a dramatic modernization, the town is still struggling to quell the illegal movement of timber from one country to the other. A 2011 study conducted by the Kenya Forest Working Group estimated that timber smuggling costs the Kenyan government some $30 million in tax revenue per year.

Most of the timber isn’t secretly smuggled through the forest — rather, a legally registered consignment is usually undervalued, says Jackson Bambo, a forest officer at the Kenya Forest Working Group, who led the study. Typically, the people transporting the timber will say the consignment is made up of poles 15 feet in length, for example, but, in fact, are 17 feet long, Bambo says.

But it soon may be harder to pull off such tricks.

With funding from the Japanese government, a new border point is being constructed, which will centralize all the government agencies into one building. Currently, they are scattered along the central road in temporary trailers that are little more than shipping containers with windows. More thorough checks will also be introduced.

Similar border points are being constructed all along the 480-mile Kenya-Tanzania border in an effort to streamline trade between two of the region’s biggest, and fastest-growing economies. The projects also aim to cut down on timber smuggling.

The demand for timber in Kenya is projected to rise by more than 20 percent by 2032, according to the Kenya Forest Service, and supply will likely be unable to keep up. That means the incentives to continue smuggling timber will likely endure.

Intervening in Charcoal

It remains to be seen how much both governments will clamp down on the informal, or rather unsanctioned, charcoal trade. In early October in Namanga, a group of Tanzanian and Kenyan police evicted some two dozen charcoal vendors from where they had been selling for years, within a 200-foot-wide No Man’s Land that lies along the border between Kenya and Tanzania.

Scuffles like this are likely to continue, or perhaps even increase as the border points become more formalized.

A bus stop in Namanga with the new border point under construction in the background. (Photo: Nathan Siegel)

When agreeing to construct the single, joint border point, the two governments also agreed to clear the No Man’s Land of vendors. There is a presence there not just of charcoal traders but also people who sell clothes, food, and a variety of other goods.

Charcoal, Africa’s favorite fuel, is used in the open without difficulty. But in the Kenyan county that includes Namanga, it has been banned because of its environmental cost, namely deforestation.

While the sale of charcoal doesn’t qualify as smuggling, its black market status means governments are losing out on millions of dollars in taxes. The Kenya Forest Working Group estimates that the Tanzanian government is losing approximately $4 million per year from the unregulated charcoal industry on the border with Kenya.

New Opportunities

While informal trade is being pushed to the town’s periphery, making it more difficult for many to make a living, others are finding Namanga ripe with new job opportunities. A flurry of new banks and schools signal the town’s growth.

Yet that’s not necessarily a sign that this dusty outpost is on track to become a thriving city.

Tanzanians play pool at the Sacha Hotel on the Tanzanian side of Namanga. Locals cross to border constantly to shop, party, or visit friends. (Photo: Nathan Siegel)

While Namanga could become a central transit point for goods and professionals, it’s unclear whether it will become a major destination for either. The nearest university is 50 miles away in Kajiado, Kenya.

Though small-scale entrepreneurs are make a living transporting essentials like clothing and charcoal across the border, Namanga still has a long way to go to attract professionals like Martin Rawago. A 30-year-old contractor for the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service, Rawago, whose family is originally from Namanga, is the kind of skilled worker the town needs.

But he isn’t sold on moving back — yet.

The main downside to Namanga, he says, is the aforementioned lack of higher education. There’s also the heat: “it’s too much,” Rawago said. But he thinks Kenya’s new constitution of 2010 that decentralized the government has been successful at bringing a lot of money in at the town level. He says Namanga has changed so much since his last visit, “I don’t even recognize it.”

The Rise and Fall of Businesses

Some business owners agree that the town is on its way up. Depending on their industry.

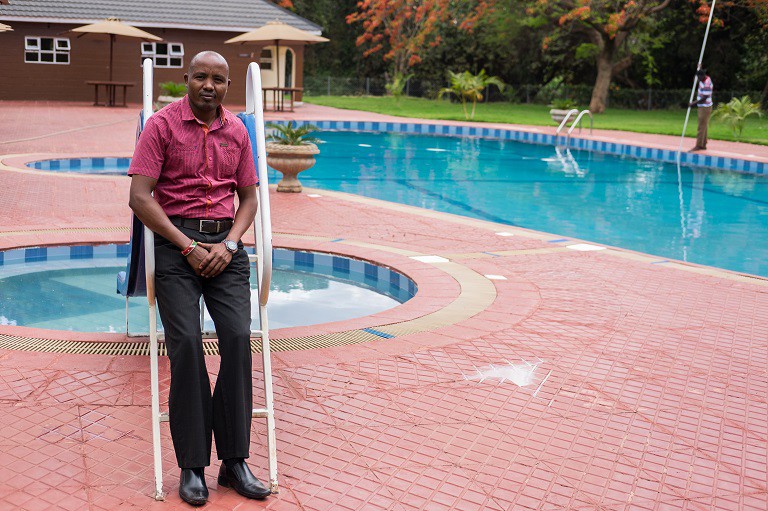

Stanley Le Shao, manager of the Namanga River Lodge, poses for a portrait in front of the hotel’s newly renovated pool. (Photo: Nathan Siegel)

“Namanga is booming,” Stanley Le Shao said. Manager of the high-end Namanga River Lodge, Le Shao says the vast majority of his customers are business people traveling between the two countries.

For lodges as fancy as Le Shao’s in the rest of the country, tourists are usually the main clientele. In fact, they used to be in Namanga: The most popular route from Nairobi to the famous Amboseli National Park used to pass through here. In 2004, a road was built farther north, cutting travel time down.

Now, fewer tourists pass through and even fewer actually stay.

“What is this town even called?” Alex Young, 23, asks. Young is a tourist from Australia heading to Nairobi from Arusha with a group of half a dozen other travelers. They have been here no more than an hour and are about to head out.

As a keepsake from Namanga, they purchased a necklace using an Australian dollar.

Salome Mbuthi, 35, the manager of Namanga Mountain View Curio Shop, which sells woodcarvings and other trinkets to tourists, says business is struggling. Her parents opened the curio shop in 1990 and soon they were expanding the store what now looks more like a warehouse. They used to have more than 20 full-time employees, many of whom were carvers who would produce work right in the shop.

But since 2004, when the route to Amboseli was changed, followed by the post-election violence in 2007 and subsequent terrorist attacks, tourism has fallen off a cliff.

Salome Mbuthi, 35, the manager of Namanga Mountain View Curio Shop, poses in her shop. Business has plummeted in the last decade or so due to terrorist attacks and the post-election violence in 2007. (Photo: Nathan Siegel)

“It used to be like an airport in here, there were at least 1,000 people a day,” Mbuthi said. Today, they have had 12 customers.

Now, only Mbuthi and one other employee work in the massive curio shop. All the carvers have left town for greener pastures. Four other curio shops have opened in the last decade and already two have failed. In 2014, Mbuthi had to start farming to make ends meet — she grows tomatoes and onions, but still hasn’t made much profit. It’s no surprise when she says she doesn’t want any of her three children to take over the curio business after she retires.

Regardless, Mbuthi is cautiously optimistic.

Hoteliers in the area tell her a fair number of tourists are booked for the coming high seasons. Her main worry now is if the upcoming presidential elections, which are set to take place mid-2017, turn violent.

“It would be a disaster,” she said.

There are already signs of the election. In the restaurant next to Mbuthi’s curio shop, a group of Maasai have gathered from across town to discuss who they will vote for over plates of barbecued goat.

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.