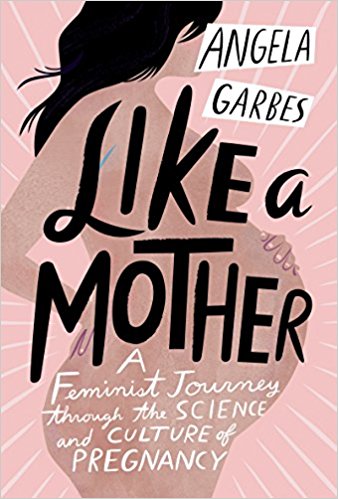

Angela Garbes was fed up with the pregnancy and parenthood resources, manifestoes written by doctors or privileged mothers who present their opinions as definitive. And so Garbes, a writer based in Seattle, Washington, set out to write her own narrative. Her book, Like a Mother: A Feminist Journey Through the Science and Culture of Pregnancy, which came out earlier this year, is at once a piece of personal narrative, science journalism, and cultural criticism.

“In American culture, motherhood is inextricably tied to the language of morality,” she writes. “Over and over, the message reinforced to expecting mothers is that there’s a ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ way to do things.” From miscarriages to pelvic floor health, Garbes’ book is never holier-than-thou or overly prescriptive. She understands that women of color, lesbian and queer women, people who don’t fall within a gender binary, survivors of trauma, and single moms are often excluded from the pregnancy conversation. With Like a Mother, Garbes set out to investigate not only the moralistic worldview propped up by traditional baby books and resources, but also the morbid fascination American society has with pregnant bodies—touching women’s bellies without consent, offering unsolicited advice, staring at pregnant women as if they had grown not a small bump but a second head. As Garbes explains so succinctly: “As you carry bags of groceries out of the store, perhaps balancing one atop your belly, a man passing by won’t offer to help you, but will ask, ‘Whoa, you sure you should be doing that?'”

Pacific Standard spoke with Garbes to discuss childbirth, baby books, and the difficulty of balancing a career and a newborn.

Writing a book is hard enough—doing so with a child seems incredibly difficult. How have you managed the balancing act?

It’s been incredibly challenging. I only have so much energy to give; when it’s gone, it’s gone. When you have a new baby, you naturally turn inwards to a very domestic place, which is very much at odds with the work of promoting a book and being public. I was unprepared and sort of naive about what it would be like. I felt depleted, physically and emotionally, for a long time. But as the book has made its way out into the world, the feedback I get from people and the conversations that the book has been creating have fed me.

As far as the baby, she’s always the priority. It’s never been difficult to prioritize that. It’s actually been beneficial in terms of doing appearances and interviews because I feel so close to the subject matter. The book is about my pregnancy and the birth of my first child. In my heart of hearts, I think that I should not have to do anything for a year; I should be on leave collecting salary. But that’s not within the realm of reality.

Whose idea was it to insert your own personal experiences into this book?

The book was not pitched as anything related to memoir. I didn’t ever think that I would do that, in part because, as a woman of color [and] as someone who is approaching 40, I never assumed anyone would care enough about my story. Initially, I wanted the book to be an exploration of the emerging science. I always thought that science is reflective of our culture. As I began writing, I realized when you’re talking about female reproductive health, our concept of science does not include female bodies—or it didn’t centuries ago. That’s where that kind of cultural critique started creeping into the book.

I also realized that these subjects are so personal. It felt at a certain point that there was no way to write about this without getting personal. I’m someone who believes in the power of storytelling. I saw my personal stories as an emotional access point. When someone relates to you emotionally, then you have their attention. Let’s talk about the science of the placenta. Let’s talk about labor. Let’s talk about breast milk. You can really hit people with facts and information.

I didn’t not anticipate this but by far the best feedback that I get is from Filipina people and women of color who feel seen. This is the first time I’ve read a book about motherhood that I feel includes me.

When I became a mother, I was 21 and in an abusive relationship so I had a limited scope of what to look for. I would say even more of a limited scope than someone who might be married or little bit older than I was. My pregnancy was completely unplanned. I always felt, and you say this well, that there’s this type of pregnancy and motherhood literature written by WebMD or white women that has a way of talking at you without giving you information.

The way that we talk about pregnancy and motherhood is very directive. It’s instructive. It’s prescriptive. It’s moralizing. I still read every book. Back then, I wasn’t thinking that I was going to write a book, but, as I was reading [the classics], I felt like I was suspending my critical mind. In the canon of pregnancy literature, you can’t get away from that tone and premise. I would read things and glean the information that I wanted, but, overall, I felt let down by the genre—and I wasn’t the only person.

(Photo: Harper Wave)

I particularly enjoyed how you use the gender binary as a vehicle to explore simplistic narratives around motherhood and childbirth.

It was really important to me to acknowledge gender issues around pregnancy. Because I’m a woman of color, this book was always going to be an intersectional feminist book. I’m very aware that the main beneficiaries of feminism have, to this point, been white women, and I feel left behind on a regular basis. It was very important to me that I write a book that brought people along and at least acknowledged those who are marginalized. Trans pregnancy, that’s not my story to tell. The experience of being a black woman and being pregnant, that’s not my story to tell. Being queer and being pregnant is not my story to tell. But that shouldn’t stop me from trying to include those people.

I’d been thinking a lot about this after I’d interviewed the midwife, Simon, and they are trans. We talked a lot about that transition and how it parallels pregnancy—that’s what Simon thinks. I wrote about this in the book, that gender transitioning is very similar in some ways to pregnancy. It’s hormonally related, and your body changes; even if it’s a welcome change, you can have feelings of ambivalence. I do believe that binaries are limiting us and don’t serve us well.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.