Where should we go from here?

By Dwyer Gunn

ITT Technical Institute campus in Canton, Michigan. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Yesterday, ITT Educational Services, a large for-profit education company currently serving approximately 45,000 students, announced it was closingalmost all of its campuses. The news comes a week after the Department of Education imposed sanctions on the company, forbidding it from enrolling any new student federal financial aid recipients. The institution’s accreditor, the also-beleaguered Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, determined in early August that the company’s campuses were not “in compliance, and [were] unlikely to become in compliance with [ACICS] Accreditation Criteria.” The publicly traded company has been accused of predatory student lending and misleading recruitment practices.

In a statement released in August, Secretary of Education John B. King Jr. explained the government’s decision-making process around the sanctions: “Looking at all of the risk factors, it’s clear that we need increased financial protection and that it simply would not be responsible or in the best interest of students to allow ITT to continue enrolling new students who rely on federal student aid funds.”

In a blog post published yesterday, King laid out the options now available to current ITT students. Students can apply to have their loans discharged, which also eliminates students’ ability to use their ITT credits elsewhere. Or students can attempt to find a different, accredited institution willing to accept their ITT credits so they can continue their education (in which case, loan discharge isn’t an option). ITT had previously been required to post a $90 million surety bond with the government, which will go toward loan forgiveness; taxpayers will foot the rest of the bill.

The announcement has elicited mixed reactions. Opponents of the for-profit education industry have cheered the government’s recent aggressive action against the schools. But experts also point out that the closure of one school doesn’t solve the industry’s larger problems. Former students, for example, are not eligible for loan discharge (unless they can prove they were defrauded) and many will still struggle to pay large debts on limited incomes. And current ITT students desperate to find an institution willing to accept their transfer credits may now be vulnerable to the outsized promises of other sub-par schools.

There’s little doubt that the for-profit industry has perpetuated a pretty major scam on thousands of low-income students.

At this point, there’s little doubt that the for-profit industry (or at least many of its players) has perpetuated a pretty major scam on thousands of low-income students. Last summer, Pacific Standard editor Michael R. Fitzgerald described working in an industry whose sales teams deftly maneuvered throughout the 2000s to attract low-income students who were under-qualified for the education they would receive. “Most for-profit college students are raised poor, are poor when they enroll in college, and remain poor years after leaving school, usually without a degree — and almost always saddled with debt,” Fitzgerald wrote, summarizing a Brookings study from 2015 that found a stark contrast in the outcomes for students from for-profit colleges and public and private, non-profit colleges.

The economists David Deming, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence Katzhave similarly found that graduates of for-profit colleges have lower earnings, higher unemployment rates, and a lot more student debt than graduates of community colleges. They are also quite a bit more likely to default on their student loans. In fact, researchers attribute much of the current student loan “crisis” to the ballooning of the for-profit sector.

But much-needed efforts to regulate the industry shouldn’t ignore the fact that there’s a legitimate reason so many students flocked to these institutions, aside from the questionable recruiting practices and overblown promises that also played a role in driving demand. In this age of globalization and technology, a high school degree no longer ensures a middle-class lifestyle. Post-secondary education, whether a degree or a certificate/credential, remains one of the best routes to economic security, but our country’s community colleges and public institutions, having seen their funding gutted by state legislatures, simply cannot meet the rising demand for higher education.

In an article published in The Future of Children in 2013, Deming, Goldin, and Katz explored the motivations of students at for-profit colleges. They concluded that, while community colleges offer many of the same conveniences that for-profit schools so aggressively advertise (online classes, evening classes, certificates in in-demand fields, etc.) at a lower cost, they are struggling with capacity in the face of budget cuts and pressures. In a survey of community college students conducted in 2011, 37 percent of students reported that they were unable to enroll in at least one course because the course was full. Twenty percent of students reported that they “have had trouble enrolling in the courses that they needed to get their degree or certificate.” In other words, some students at for-profit schools may not be deciding between a for-profit school and a community college, but rather between a for-profit school and no school at all.

The limited evidence to date, in fact, suggests that students and the for-profit education sector respond to community college funding changes. In a 2009 paper in the American Economic Journal, Stephanie Riegg Cellini, an economist at George Washington University, studied the effects of increased community college funding in California, in the form of approved local community college bond referenda. Cellini found that “bond passage diverts students from the private to the public sector and causes a corresponding decline in the number of proprietary schools in the market.”

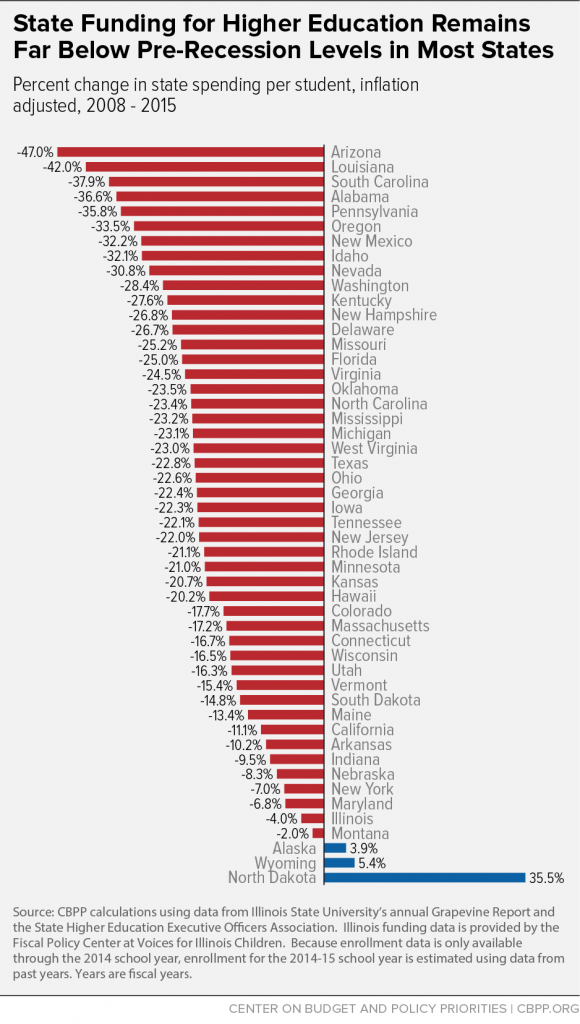

In the wake of the Great Recession, states dramatically cut funding for higher education. While a number of states have begun to reverse this trend, overall higher education funding remains well below 2007 levels, as the chart at left from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities illustrates.

Nationwide, state spending on higher education was 20 percent lower in the 2014–15 academic year than it was in the 2007–08 academic year. It’s time to start re-investing in our public institutions of higher learning — it’s good for low-income students and may also be the most effective way to rein in the for-profit education sector.