Over the weekend, the New York Times ran a piece claiming that the Democratic Party is in the midst of a revolution, with young progressives challenging the older establishment for influence in primaries and control of the party. In actuality, there’s good reason to believe the progressive insurgency is overhyped right now but could be affecting the party in the long term.

The idea of the Democrats being hopelessly divided is a perennial critique and media narrative dating back at least a century. But how divided is the Democratic Party today compared to how it’s looked in the past, or compared to the Republican Party?

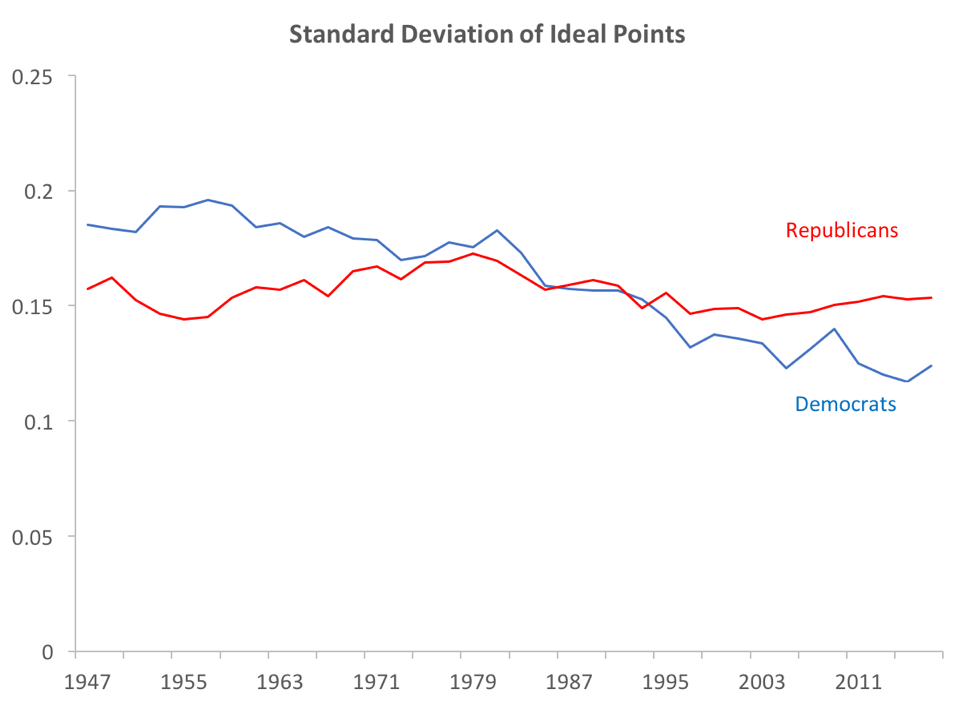

One straightforward way to examine this is to look at the spread of ideal points—that is, an estimation of a politician’s ideological preferences based on voting record—in Congress. Using Voteview’s voting data and calculating the standard deviation of both parties’ ideal points for each year since 1947, it seems the Democratic Party has actually become a much more unified caucus over time, largely due to the exit of conservative white southerners from its membership. For several years now, Democrats in Congress have been considerably more homogeneous than their Republican colleagues, a narrative that runs counter to most media coverage of the Democratic Party.

Now this, of course, doesn’t necessarily mean there’s no ideological rift brewing within the Democratic Party in this year’s elections. Here it’s helpful to turn to an an ongoing investigation by the Brookings Institution, called the Primaries Project, which examines campaign literature produced by Democratic congressional candidates to determine who is “progressive” and who is “establishment.”

Among the Primaries Project’s most significant findings: Establishment Democrats are faring somewhat better in primaries than their progressive counterparts, with 30 percent of the establishment Democrats winning their primary races but only 23 percent of progressives winning. That said, 23 percent is pretty impressive for a group of relatively inexperienced and often under-funded candidates. Progressives are making up a substantial portion of the new candidates voters will see on their ballots in November.

It’s also vital to look at where these candidates are running. The self-described progressives are predominantly winning in more conservative congressional districts—a quarter of them are running in districts with a Republican lean of more than 15 points, the Primaries Project researchers note. They are winning, that is, in districts that the party at large is generally not focusing on, and where they have little chance of winning in November. (That makes New York’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a self-described Democratic socialist who took down a well-funded establishment Democratic incumbent, highly unusual.)

But the progressive insurgency can have other effects on the Democratic Party. Even where these progressive candidates are unsuccessful in the primary, the establishment Democrats who defeated them want to secure the support of an increasingly enthusiastic and mobilized group of activists. Following the Democrats’ 2016 presidential loss, there was a feeling in the party that it had failed to maintain the interest of the activist left; candidates are not eager to repeat that failure.

We can see the effect on this in the spread of support for movements like Medicare for All and Abolish ICE among Democratic congressional candidates—even among 2020 presidential candidates. These policy commitments, once made, are difficult to walk back. Moreover, if Democrats perform well this fall (as many forecasts suggest) while championing such talk, that would likely serve as a lesson to the 2020 field of candidates that progressivism is a winning message.

In the short term, we’re not really seeing a revolution. But in the long run, this is how a party moves leftward.