Odds are, the U.S. will enter into another recession sometime within the next few years. What should the government do?

By Dwyer Gunn

An abandoned home seen in Detroit, Michigan. (Photo: Mira Oberman/AFP/Getty Images)

Sometime in the next three years, the United States economy will likely enter another recession. And if it doesn’t happen within the next three years, it will happen sometime soon after that. Even the most carefully managed and structurally sound economies experience cyclical slowdowns. So what should our lumbering, hyper-partisan government—in many respects still feeling the effects of the Great Recession—do if and when that happens? And what can it be doing now to prepare? Those questions were the topic of a discussion between Larry Summers, the former secretary of the Department of the Treasury and director of the National Economic Council, and Shaun Donovan, the current director of the Office of Management and Budget, hosted earlier this week by the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution.

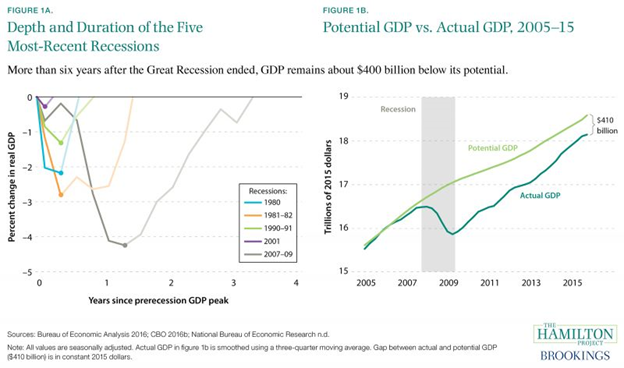

The Great Recession, which officially lasted from December 2007 to June 2009, was the most severe and prolonged slowdown of the last 50 years. America’s economic recovery has also been much slower than previous recessions. Today’s labor market is still weaker than the pre-Recession labor market, and economic output is still below potential gross domestic product (GDP). Economists define “potential GDP” as the level of economic output an economy can produce without increasing inflation rates.

The figure below, which comes from a new report from the Hamilton Project, illustrates the severity of the Great Recession and its continued effects on the economy:

(Graph: Brookings Institution)

“If we look at the period from 1929 to 1940, and what happened to GDP per adult and we look at the period from 2008 to 2019, it is equivalent,” Summers pointed out at the event. “In others words, the 11 years after 1929 will have been no more worse in terms of the endpoint to the 11 years that we have just been through.”

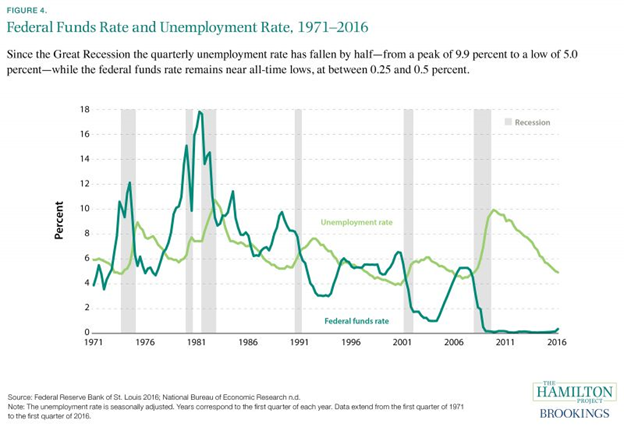

Generally speaking, governments can respond to economic conditions with either monetary policy or fiscal policy. The former takes the form of central bank policies that control the supply of money, which then affects inflation and interest rates. Fiscal policy, by contrast, is characterized by changes in either government spending or tax levels. During the Great Recession, the U.S. government utilized both—those controlling the Federal Reserve System dramatically decreased interest rates to historic lows, and Congress passed several fiscal stimulus packages comprised of tax cuts and government spending increases meant to boost economic output.

We’re not doing much to spur economic growth these days.

But Summers and a number of other economists argue that the policy options for the next slowdown are decidedly more limited. The Federal Reserve System, in the face of a painfully slow recovery, has kept interest rates very low and has already employed a number of other alternative expansionary monetary policies. With interest rates already pretty low, the System won’t have much room to further reduce rates in a near-term recession.

Here’s what the federal funds rate looks like right now (it’s that dark green line that, for much of the last five years, has stayed virtually at zero):

(Graph: Brookings Institution)

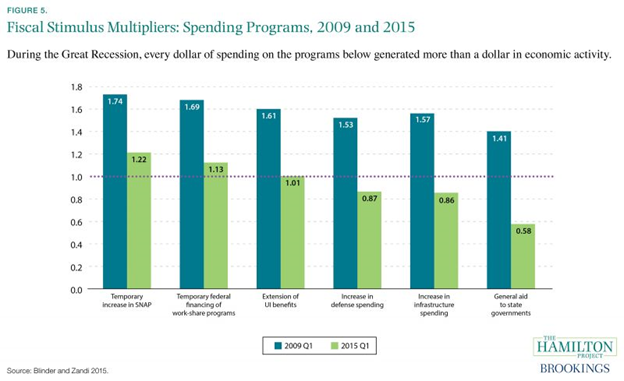

That leaves fiscal policy. Though policy unfortunately requires congressional action, it has the advantage of being highly effective at increasing GDP. Economists even have a fiscal multiplier, which provides them with a way to measure a given fiscal stimulus’ potency. A fiscal multiplier measures how much, if any, economic output is produced by government spending or tax cuts. A program with a fiscal multiplier of 1.5, for example, produces $1.50 worth of economic output for every dollar of government spending.

As the figure below demonstrates, the various government spending stimulus measures implemented during the Great Recession were extremely effective at increasing output during the crisis years, although the fiscal multiplier effects of these policies have declined as the economy has recovered (which is consistent with economic theory):

(Chart: Brookings Institution)

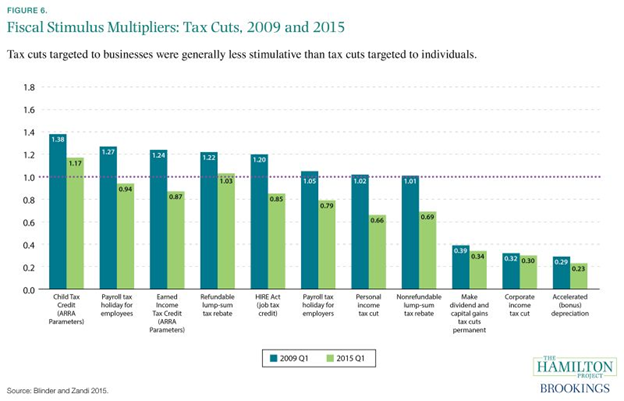

Tax cuts, most Republicans’ preferred fiscal stimulus, work as well, but they generally provide less “bang for your buck” (i.e. their fiscal multipliers are lower) than government spending increases, particularly if those tax cuts take the form of corporate tax breaks:

(Chart: Brookings Institution)

The Hamilton Project report includes a number of policy proposals aimed at improving the government’s response to the next recession. The proposals touch on everything from revising Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program rules, to making the programs more supportive and responsive in a slowdown, to reforming our entire fiscal policy system so that it can more quickly respond to a recession. But a growing chorus of liberal economists, including Summers, is arguing that perhaps the biggest focus for the government is something that would also help people today: a renewed focus on economic growth, which is depressingly anemic by historical standards.

There are plenty of legitimate concerns about the growth of the 1 percent and whether Americans of different races and income levels will benefit equally from higher rates of economic growth and productivity, but there’s little doubt that increasing our growth rate will help workers across the income spectrum. In tight, fast-growing economies, low- and middle-income workers will have more leverage to negotiate higher wages and better benefits, and the government will have more tax revenues to direct toward the poorest of the poor.

“I am here to tell you that the most important determinant of our long-term fiscal picture is how successful we are at accelerating the economy’s growth rate in the next three to five years, not the austerity measures we have,” Summers said. “Anyone concerned with our long-term fiscal health should be re-doubling their focus on the currently inadequate growth rate.”

Unfortunately, we’re not doing much to spur economic growth these days. After the Great Recession, legislators, buoyed by a wave of Tea Party fervor, set out to tame the national debt, in a movement that has had disastrous consequences and which some blame for the current slow recovery. “One of the most profound mistakes was Congress shifting toward austerity and a set of manufactured crises that hurt the economy,” Donovan said. “So if you look at the combination of sequestration and the government shutdown, you’re looking at likely over a million jobs lost as a result…. It is enormously important that we learn the lesson that shifting to austerity was a substantial mistake in the aftermath of the Great Recession.”

Summers and Donovan laid out a number of strategies to spur economic growth: immigration reform (more immigrants means more workers), paid family leave or childcare credits (to encourage women to stay in the labor force), tax reform (to increase investment), regulatory reform (to spur innovation), and public infrastructure investment.

But what’s perhaps most needed is a commitment from lawmakers to utilize the best of liberal and conservative doctrine to increase economic growth — through both public investment and the empowerment of the private sector. In Summers’ words, “[w]e need a strategy that moves beyond the shibboleths of both parties.”

||