White people in the United States are finally starting to understand what institutional racism looks like.

In the nine months since the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, white Americans have been forced to reckon with the reality of racial bias in law enforcement more directly than at any other time since the brutal 1992 beating of Rodney King. And Brown, unfortunately, was just the beginning: Eric Garner in New York, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Walter Scott in South Carolina, and Freddie Gray in Baltimore. The seemingly endless succession of black deaths has sparked massive protests and a digitally infused new civil rights movement. It’s been a wake up call for white Americans.

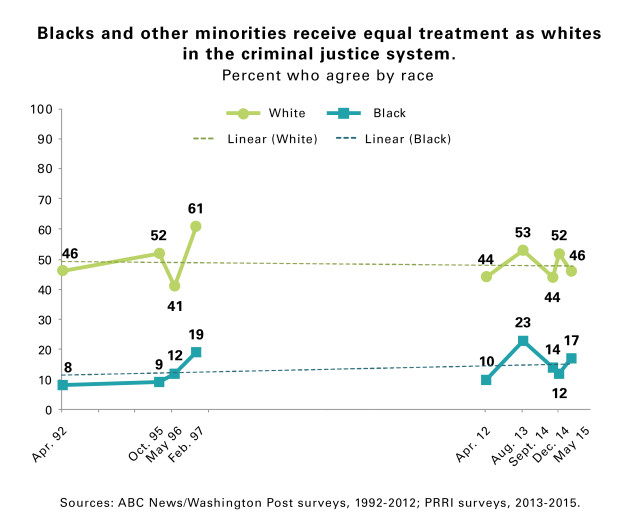

But have they heard the message? New data suggests that while a vast disconnect remains in how white and black Americans regard the U.S. justice system, more white Americans are coming to grips with the inherent biases baked into the foundational bricks of law enforcement.

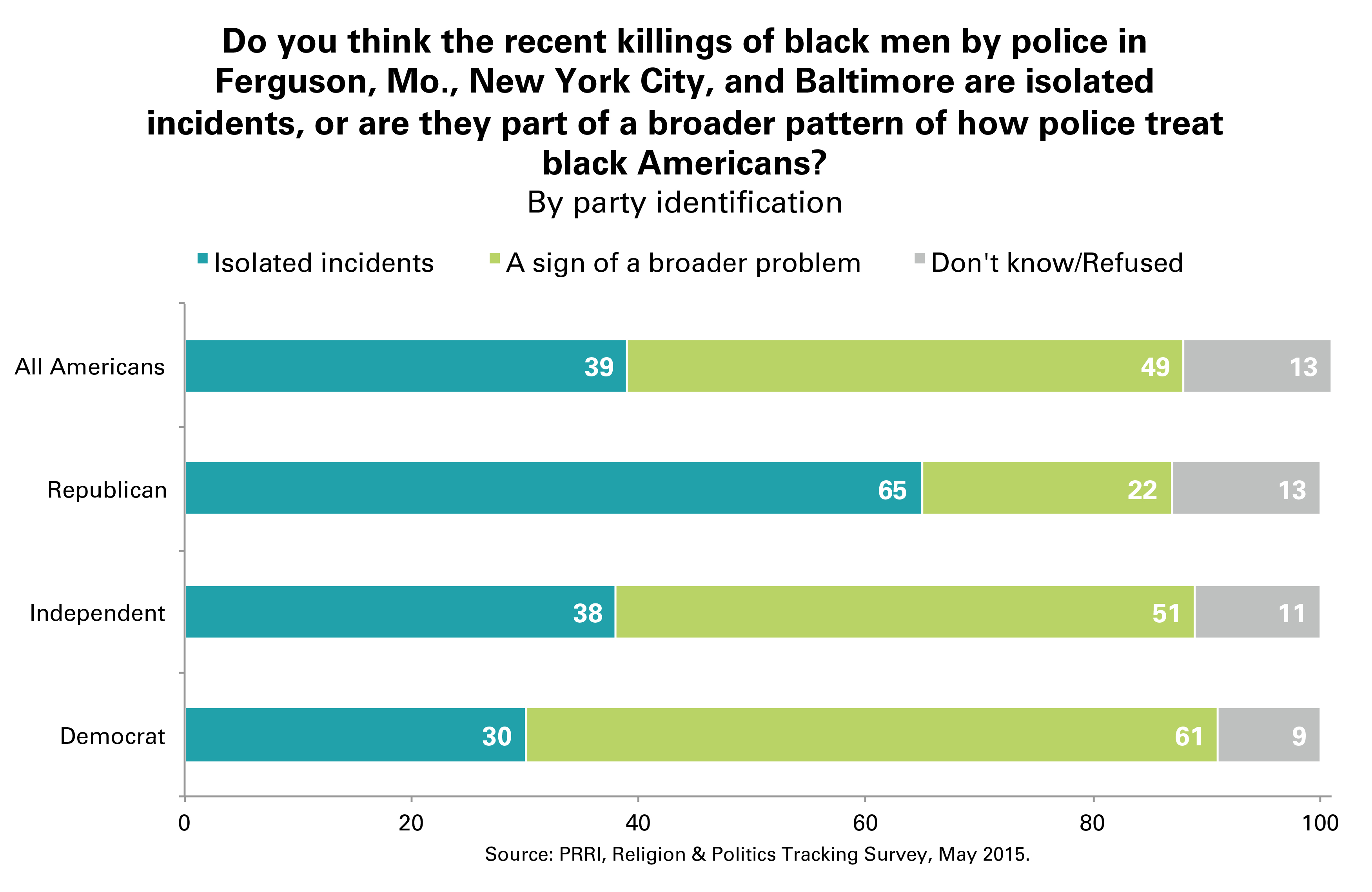

According to new research from the Public Religion Research Institute, 49 percent of Americans believe deaths of black men at the hands of police in Ferguson, New York, and Baltimore are “part of a broader pattern of how police treat black Americans,” up from 43 percent in late 2014. By contrast, 39 percent said they were isolated incidents, down from 51 percent in 2014.

Young or old, black or white, Democrat or Republican, all Americans saw institutional racism more clearly than ever.

PRRI attributes this to changing attitudes among white Americans. The number of white people who said the killings were isolated incidents dropped from 60 percent in 2014 to 45 percent today. Similarly, 43 percent said the killings were part of a broader pattern of behavior among police, up from 35 percent in 2014. Views among black Americans are identical in both time periods. Nearly three-quarters of black Americans today (74 percent) and late last year (74 percent) say that recent killings of black men represent a pattern of behavior by police.

Naturally, this change in attitudes wavers when broken down by political orientation.

But at the same time, this latest batch of PRRI data jives with the organization’s research published in the immediate aftermath of the unrest in Ferguson, which showed that 56 percent of Americans disagreed that the criminal justice system treats whites and minorities equally, up from 47 percent in 2013. This viewpoint was spread across racial and political lines; young or old, black or white, Democrat or Republican, all Americans saw institutional racism more clearly than ever.

This is a good sign; an indication that white Americans are beginning to take institutional racism—especially that attributed to racial bias in law enforcement— seriously. But don’t expect change to come anytime soon: PRRI’s data shows that the massive gap in how white and black Americans trust law enforcement has changed little over the past 25 years, despite high-profile instances of police brutality and resulting public outcry. While the New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb noted in the aftermath of the Baltimore riots that, “with the exception of the riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., every major riot by the black community of an American city since the Second World War has been ignited by a single issue: police tactics,” it seems that unrest doesn’t change minds the way we might imagine, or hope.

Don’t expect politicians to help either. Consider this week’s election of Daniel Donovan, the prosecutor widely faulted with skewing the Eric Garner case, to represent State Island in Congress. The protests stemming from Garner’s death, despite grabbing headlines, were barely mentioned during the race. In the presidential race, Hillary Clinton can wink and nudge at criminal justice reform all she wants, but until the number of white Americans focused on disparities in criminal justice reaches a critical mass, black lives—and the police who end them—will never be a salient political issue.