There was a little tussle last week in the world of conservative media. The Media Research Center had selected Fox News host Sean Hannity to receive its annual William F. Buckley Award but then rescinded the offer, apparently due to Buckley’s son Christopher being uncomfortable with the choice. Hannity disputed the official account somewhat and claimed that a scheduling conflict prevented him from attending the award ceremony.

On its face, this is a minor story. But it is emblematic of a larger struggle within modern American conservatism in the Trump era. It is not an exaggeration to say that conservatism is experiencing a civil war, and the Buckley award was simply a moderate skirmish in that war.

Broadly defined, conservatism is divided into two main camps right now. There are those who identify conservatism largely as Buckley defined it—a set of beliefs in limited government, low taxation, minimal regulation, local control, and individual liberty. It contains substantial faith in free-market capitalism as the optimal means of advancing the greatest good for the greatest many, and it includes an historic hostility toward illiberal, non-democratic regimes, particularly Russia. This set of beliefs often contains some prescriptions about individual behavior—a veneration of (heterosexual) marriage and (Christian) faith, calls for upright moral behavior, respect for heritage, etc.

The other camp in modern conservatism is probably best identified with Hannity, although former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich has become an enthusiastic advocate. This camp simply defines conservatism as whatever President Donald Trump is currently saying. Sexual assault, multiple marriages, support from Julian Assange, inconsistent policy stances, a clear ignorance of religion and history, support for an expanded welfare state, government intervention in businesses, etc., are no longer a problem when Trump is doing them. Russia is now an old friend, or at least a trusted ally when it comes to the vital national task of not electing Hillary Clinton.

Because Trump ran against and defeated Clinton, the multi-decade bête noire of American conservatism, he is seen as the true champion of conservatism, and anything he does is, by definition, conservative. Moreover, strong leadership is itself a tenet of this strain of conservatism, so supporting the leader, whatever his beliefs, is considered a vital act of patriotism.

Both sides of this war call themselves conservatives, and neither is obviously wrong, although both cannot simultaneously be right. I am drawing here on Hans Noel’s framework in his book Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America. As Noel notes, ideologies are constantly being framed and fought over by thought leaders. There’s no automatic or natural definition of conservatism or liberalism. More Noel:

There are deep debates among conservative thinkers, and whoever ends up convincing more people wins. You can say, “That’s not real conservatism,” but … at the end of the day, you’re wrong if no one agrees with you.

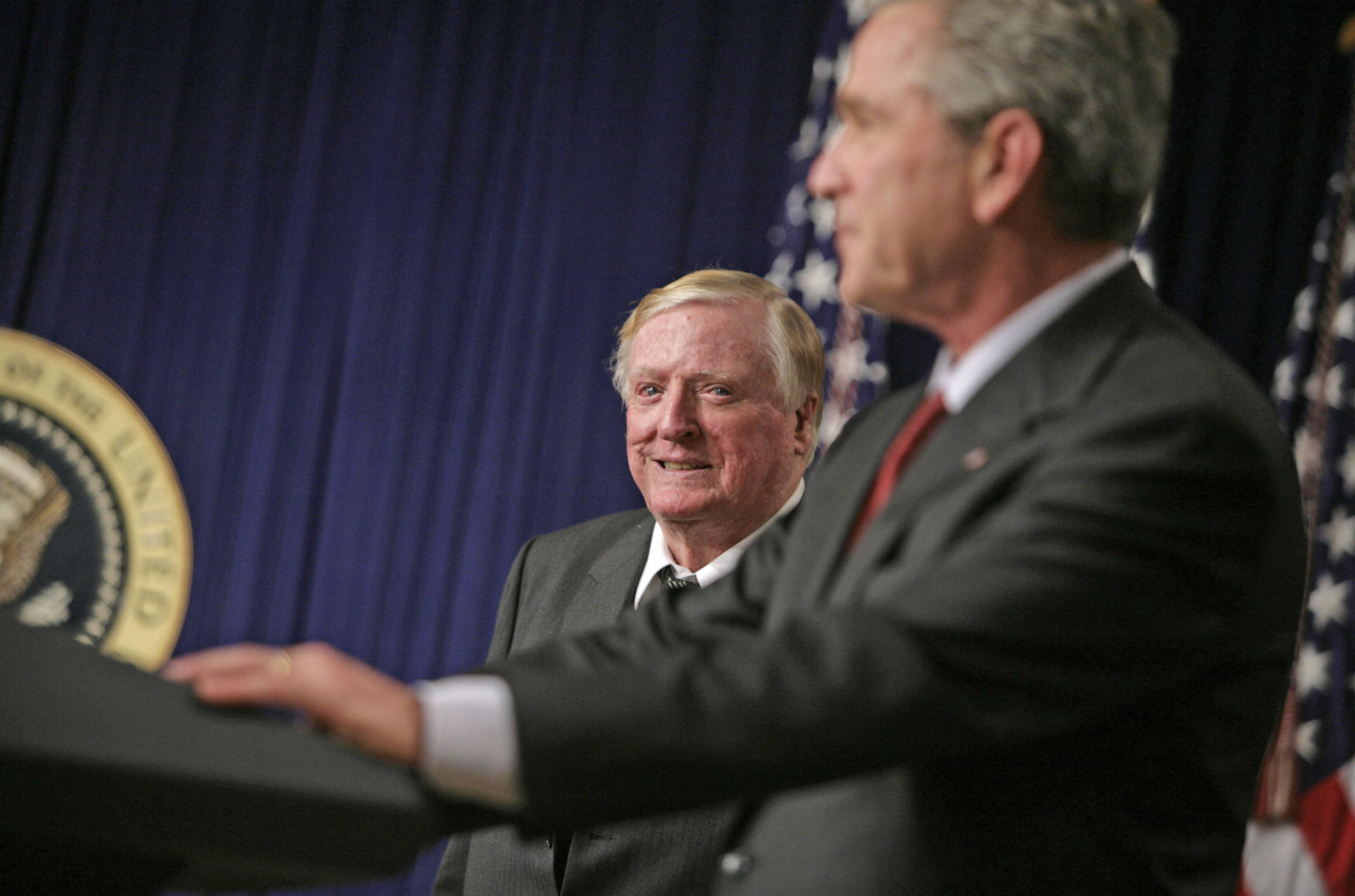

(Photo: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

Arguably, this war has been going on for some time, but the Republican Party has minimized public skirmishes by nominating presidential candidates who at least nominally adhered to the Buckley camp. This adherence was never perfect—even conservative icon Ronald Reagan raised taxes and forged agreements with the Soviets—but it was generally credible enough. Both Buckley-style and Hannity-style conservatives could be reasonably happy with nominees like George W. Bush or Mitt Romney, for example.

In nominating Trump, however, Republicans had picked someone who clearly had no allegiance to, or even an apparent understanding of, Buckley conservatism. The National Review made the Buckley-style case against Trump back in January of 2016, describing him as a “philosophically unmoored political opportunist who would trash the broad conservative ideological consensus within the GOP in favor of a free-floating populism with strong-man overtones.” Other ideological leaders found an expansive enough definition of the ideology to embrace Trump and support his bid for the nomination. The divide within modern conservatism quickly rose to the surface and has only become more strident since that time.

This war is not likely to end any time soon. Indeed, it could flare up further if Trump remains unpopular in his bid for re-election. It is not too difficult to imagine a more traditional conservative challenging Trump for the Republican nomination in 2020. The war would continue if Trump won re-election, and, if he lost, each side would blame the other for it.

It’s perfectly normal and healthy for thought leaders to fight among themselves over just what their ideology means. Liberals have a more unified version of their ideology than they did a few decades ago—a commitment to civil rights was not always universally embraced on the left, for example—although they still obviously fight a good deal. But conservatism is facing a very difficult divide right now, one that is likely to affect the party system and American politics for decades to come.