In case you’ve missed it, there’s been a spate of op-eds recently blaming President Obama for a lack of leadership; Obama could have gotten Republican members of Congress to agree on gun control, tax increases, and many more of his legislative priorities if only he knew how to lead. What “leading” means is usually left rather vague. Ron Fournier believes it just involves “rising above circumstance,” E.J. Dionne thinks it means showing how much you enjoy your job, and Maureen Dowd thinks it means writing the names of persuadable senators on a chart, just like in an Aaron Sorkin movie. The archetype usually thrown around is that of Lyndon Johnson; he knew how to get things done, dammit. If Obama would cajole, intimidate, and horse-trade like LBJ did, the theory goes, he’d have a more impressive list of achievements by now.

Each member of Congress is elected to serve a specific geographic area of the country, and they are rewarded for representing that area and punished for betraying it.

These arguments come in many different forms, but at their base, they’re saying the same thing: Personality matters, institutions don’t. That is, a sufficiently determined president can compel members of Congress to do what he wants them to do, regardless of those members’ own priorities, concerns, and career goals.

This argument is obviously and profoundly misguided. But it’s being pushed by many of the same people who continually urge members of Congress to work past their differences, to resist the pressures placed on them by voters, and to work together for the “common good,” as though that were something intrinsically obvious.

Not to sound condescending, but there are some key elements of American politics that these pundits seem to be missing. Chief among these is that representation in the U.S. is determined by geography. President Obama is accountable to a vast constituency of over 200 million eligible voters, more than half of whom turned out to vote last year. This electorate is, by definition, moderate. The typical member of the U.S. House of Representatives, conversely, is accountable to only around 700,000 people, and they may be, on average, much more conservative or much more liberal than the American people as a whole.

Let’s just imagine a hypothetical Republican member of Congress from a conservative district. She has very little interest in working to advance the president’s agenda. Quite often, her voters will be irate with her if she works with Obama and may throw her out of office for doing so. That is to say, it is not in her professional interests to be persuaded by the president. Moreover, she grew up in that district and was selected by its voters to represent it. This isn’t some cynical game—she believes the things she is saying. That is, it is not in her personal interests to help Obama because she believes what Obama wants is actually bad for the country.

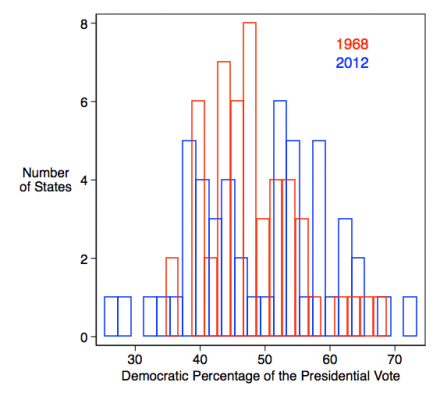

What’s more, our congressional districts and states are moving further apart from each other ideologically. Below is a histogram showing how each state voted in the presidential elections of 1968 (red) and 2012 (blue). Notice how the red distribution basically has one peak while the blue distribution has two? That’s a sign of polarization. Senators who strictly voted how their states wanted in 1968 would have behaved much more similarly to each other than those who voted their states in 2012. There’s been a similar level of polarization among congressional districts, as well.

Data from David Leip.

So could LBJ just bend members of Congress to his will? Probably not. Notably, he had a hard time getting any of his priorities passed in the last few years of his term. This wasn’t because he lost his leadership skills. Rather, his party lost its gigantic majorities in 1966 and he lost much of his popularity as the Vietnam War escalated. The institutional environment mattered a lot more than his personality traits. But even if we imagine that he did have that kind of power, he was dealing with a much less polarized Congress than Obama is dealing with today.

We can criticize members of Congress all we want for failing to get along with each other or to work for the common good, but we should keep in mind that those tasks are not remotely in their job descriptions. Under the Constitution, each member is elected to serve a specific geographic area of the country, and they are rewarded for representing that area and punished for betraying it, no matter how much of an ideological outlier that area appears to be. It’s silly to expect members of Congress to ignore their own career incentives, and it’s damned weird to blame a president for failing to get them to do so.