In the mountains of eastern Afghanistan, Sergeant Major Edward Long of the United States Army, his French guard, and six Afghan National Police officers were on a training operation to arrest a group of insurgents that the Army had identified as mid- to low-level operators. They were following a sanitation canal between qal’ats — the mud-walled compounds around many homes — when a machine gun opened fire. Long threw himself into the canal. His French guard dropped to his knee to return fire and was instantly killed. Three of the Afghan police were shot, and the rest fled.

Long was alone, armed with an M4 assault rifle and a pistol. The canal — filled with human excrement and trash: water bottles, candy wrappers, the bones of slaughtered animals — was just deep enough to protect him. There was no way to retreat without exposing himself. Bullets struck so close they threw mud into his face.

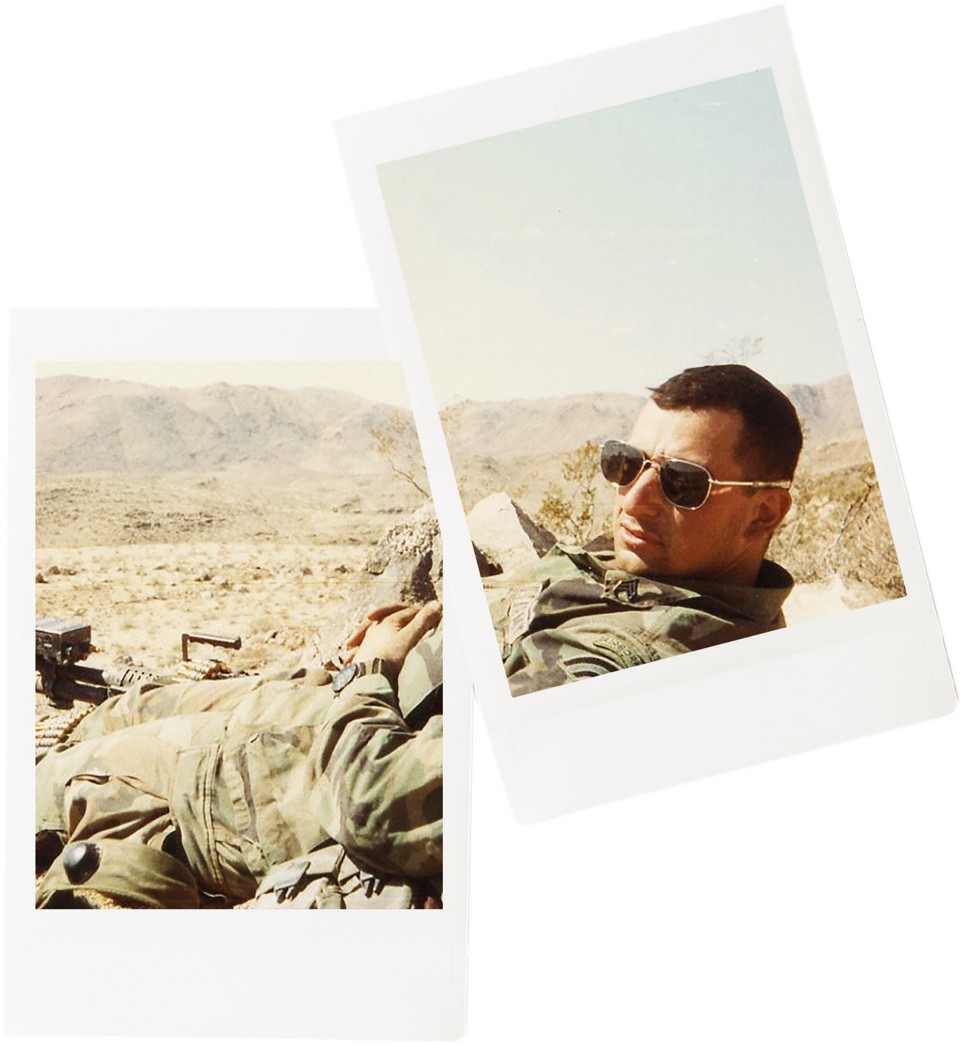

(Photo: Courtesy of Jennifer Long)

On the second floor of a house 150 meters away, he saw the muzzle flash of the machine gun. He’d spent decades in the infantry and trained alongside Special Forces, and he knew that if his attackers had received proper instruction, they would have waited until his team was closer and then fired down, killing them all. Instead, the angle of fire allowed Long to use the canal for cover.

Staring through his rifle scope, he returned fire, forcing his breathing to slow, holding his breath when he pulled the trigger. Each magazine held 30 bullets, and he did not want to waste them.

He was trying to reload quickly and avoid jamming his rifle with mud when two insurgents appeared between the qal’ats. He dropped his M4 and grabbed his pistol. In his telling of the story, he hesitated before saying, “I put them down.”

After 14 minutes in the ditch — “it felt like hours,” he recalled — a team of French soldiers and Afghan police surrounded the house, killing several insurgents and capturing the rest.

That night, in his room at Forward Operating Base Morales-Frazier, at the foot of the Hindu Kush mountains, Long pulled off his equipment. Mud and bullet casings fell out of his clothes. He stripped to the sports bra he wore to prevent his body armor from rubbing against the small breasts that were coming in, as tender as a pubescent girl’s — so sensitive that “even the water from the shower hurt.”

Over the days that followed, he shared the trauma of the firefight with a group of female soldiers. Since his arrival, they had been his allies — the only people on the base who knew that, prior to his assignment to Afghanistan, he had begun a gender transition and had been planning on leaving the military after nearly 30 years of service to start a life as a woman — as Jennifer.

Edward Long joined the Army at the age of 18, propelled by a sense of patriotism and a desire to prove his masculinity. As a 10-year-old, Edward used to watch his mother doing needlepoint, and one day he asked to be taught. His mother was confused by the request, saying, “Don’t you want to do something else?”

Edward insisted, and, as his mother showed him how to do it, he enjoyed sliding the needle through the cloth. When his father — an Anglo-Irishman who worked in trucking, on the loading docks — got home, he shouted that his son shouldn’t behave like a girl and called him a faggot.

Two years later, Edward took some clothes from his mother and sister, among them a bra and a top, and alone in his room he enjoyed putting them on. He kept them hidden under his mattress, but his mother eventually found them and told his father.

“He cracked me a couple of times really good,” Jennifer recalled, sitting across from me at her kitchen table in Kearny, New Jersey. (For the sake of clarity and by Long’s agreement, I will use the pronoun associated with the gender she is expressing at any given point in the story.) Her yellow dress had floral designs, and her dark auburn hair fell just below her shoulders. Over the course of several conversations, she returned to this story repeatedly, each time sharing more details: “That was a terrifying experience. You’re experimenting at an early age, and you don’t know why. There are things that you want to experience but you can’t. You get caught, and there are consequences. Those consequences spin you off into a life of feeling awful about it.”

Edward enlisted in 1983, when the Army still classified transgenderism as a psychosexual disorder. His attraction to the military aligned him with some striking statistics. Transgender Americans are about twice as likely to join as cisgender people (those whose self-identified gender conforms with their biological sex). According to a 2014 study by the Williams Institute at the University of California–Los Angeles School of Law, 32 percent of transgender women assigned male at birth had enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces, compared to 19.7 percent of cisgender men. As for transgender men assigned female at birth, 5.5 percent had enlisted, which is about three times the rate for cisgender women. An estimated 8,800 transgender people were on active duty in 2014, with an additional 6,700 in the National Guard or Reserves. The entire transgender military community, including veterans, was estimated at nearly 150,000.

“We join because sometimes we’re trying to overcompensate,” Jennifer explained to me. “If we become gladiators and warriors, we can justify to ourselves that we are men.”

These statistics appear to corroborate the research of Dr. George Brown, a psychiatry resident at Ohio’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the 1980s. After counseling male patients who identified as women, he wondered why they would join an organization that viewed them as having a disorder, and would discharge them if they revealed their true gender identity. In 1988 he published “Transsexuals in the Military: Flight Into Hypermasculinity,” defining hypermasculinity as a state characterized by frantic preoccupation with the need to prove manliness. In his paper, he compares interviews with 11 transgender patients, eight of them enlisted soldiers, theorizing that military service affords a male-to-female transgender individual a means of “purging his feminine self ” and becoming, in their words, “a real man.” Brown speculated that the masculine roles available in the Armed Forces resulted in “a higher prevalence of transsexualism in the military than in the civilian population.”

A growing body of research has supported this view, calling the military’s longtime ban on transgender soldiers into question, and on June 30th of this year, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter repealed it, announcing that transgender people can serve openly. It was a major victory in the American transgender-rights movement, which began to coalesce in 1959, with a clash between transgender people and police at a Los Angeles donut shop. Clashes occurred again in San Francisco in 1966 and in New York City in 1969, during the Stonewall Riots — perceived by many as the birth of the modern LGBTQ rights movement. The 1970s saw more organized activism, and, in 1975, Minneapolis was the first city to pass a law preventing discrimination against transgender people. Organizing, advocacy, lobbying, and marches throughout the 1990s brought transgender issues national attention, and, since then, 20 states and Washington, D.C., have enacted employment non-discrimination laws that cover gender identity. The 2000s saw the first openly transgender mayor as well as presidential appointees, and, in the 2010s, there have been federal protections for transgender employees and Medicare coverage for sex re-assignment surgery. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association replaced the diagnosis of “gender identity disorder” with “gender dysphoria” in an effort to “avoid stigma and ensure clinical care for individuals who see and feel themselves to be a different gender than their assigned gender.”

Many of these changes were taking place unbeknownst to Edward Long, who rose through the ranks in the 1980s and ’90s, seeking out the most challenging and traditionally masculine roles available. He served as a drill instructor, was assigned to Fort Benning and later Fort Jackson, and, after a few years, met a sergeant major — Vietnam-era Special Forces — who got him an interview with the 11th Group Special Forces at Fort Dix, in New Jersey.

Despite Edward’s extensive training, he lacked the Airborne qualifications of a paratrooper, and was sent to Staten Island to join a National Guard unit — a six-man long-range surveillance attachment whose job was deep reconnaissance. He received his Airborne badge there and went on to lead the team, which comprised some of the top non-commissioned officers in the state. They did training missions with Special Forces, traveling to Puerto Rico, Panama, Antigua, Canada, Germany, and Iceland. When Desert Storm began, they were sent to the Georgia National Guard, and spent months awaiting a deployment that never came.

Edward was married twice during this time, and, after his unit dissolved in the wake of Desert Storm, he held a number of military positions in quick succession. Trips away, frequent moves, and lean pay wore down his marriages, and a 2004 deployment to Guantanamo resulted in his second divorce. He ran prison security at Gitmo — a job he hated for its long hours and oppressive conditions, stationed inside a small room without a window, staring at security monitors and computer screens.

During those years, he found small ways to intermittently express Jennifer. He would cross-dress alone for a few days at a time before shame and disgust overcame him. He didn’t understand why he was drawn to women’s clothes.

“It would come and go,” Jennifer explained to me. “Sometimes it was in my face every day for a month or a week. Sometimes I wouldn’t think about it for a month. As I got older, it was more prevalent.”

The one pleasure Edward could maintain in public was clean, more delicate-looking hands. He’d let his fingernails grow a little and took his time ling them, squaring the ends.

One Sunday, after his second divorce and years after his father’s death, he and his mother had dinner. When he reached for a dish, she grabbed his hand.

“What’s up with these nails?” she asked.

That night, as soon as he got home, he cut them off. Years later, in Afghanistan — after his decision to change genders had been made — he maintained a single long pinky nail that he polished like a talisman: a promise to Jennifer that, after serving this one final tour, she would have the opportunity to live the life she should have been living all along.

Edward returned from Gitmo in 2005, and found himself alone in an empty apartment in New Jersey. His attraction to feminine objects grew stronger, and he increasingly turned to Jennifer for comfort, struggling all the while to understand his impulse to be what many still called a transvestite.

The Internet provided validation. “The earlier part of my life, where was I going to get information from? There was nowhere you could go. Here, with the Internet, in the privacy of the house,” Jennifer told me, “I was trying to find a definition of who I was. I started to read the psychology behind it and found the word transgender.”

Inside the apartment, she lived as Jennifer, but each time Edward had to work, he hid the women’s clothes in an Army backpack filled with gear, which he put in a duffle loaded with more gear, which he hid in the closet under a stack of military equipment. Returning home one afternoon, he saw that he’d left a pair of heels out in the bedroom. Overwhelmed with panic, he rushed to hide them. Only after he’d finished concealing them and sat down to clear his mind did the truth become apparent: He lived alone. No one else had a key.

“So I realized it was safe. I’m OK. I got the damn shoes out and put them back out in the bedroom and left them there.”

The rapidly expanding Internet taught her that she wasn’t alone. There were other transgender people, and clubs where they hung out. But Jennifer had never existed outside of the house. She had to find a way to bring herself into the world. Though she was more than ready to put the manly soldier behind her, her infantry training inclined her toward doing a little reconnaissance first.

So she “played the part of Ed” and visited a club she’d found online. She met a woman there who encouraged her to return, and, a week later, Jennifer put on a blouse and skirt and a small white jacket. She did her make-up. She looked out the window, afraid of running into her neighbors or landlord.

“It was easier to jump out of an airplane the first time than it was to turn that doorknob. My knees were shaking, my heart was racing. Everything was just so overwhelming. It was March. For God’s sake, when you’re standing outside in the cool air in a skirt for the first time, it’s a little invigorating. You feel the breeze.”

She drove to Manhattan. It was a struggle just to get out of the car. But once she did, she realized that the beauty of New York is that nobody notices you. She made her way down the sidewalk, trying to avoid the cracks in her high heels.

In the club, she saw her friend from the previous week, and, for the first time, spoke the words, “Hi, I’m Jennifer.” It was at this moment that Jennifer became real.

The friend asked if she was into guys or girls, but Jennifer didn’t know. She’d never thought about it.

When she was Jennifer, she felt as if she’d always been a woman. It was Edward who suddenly seemed like a story: the one she needed to hide. She began to engage with the world differently, to show more compassion and emotion, to be more maternal. She was relieved to no longer have to be the gruff man hanging out with the guys.

But as much as she loved being Jennifer, the reality of transitioning was something she came to hate. “The Middle World,” she called it. She spent weekends living like a woman, only to find herself in men’s work clothes on Monday morning, sobbing at the sink as she removed her nail polish. She had two sets of friends — two sets of everything — and had to be more covert than ever to keep her two lives from intersecting.

At the club, she met the man who would become her first boyfriend — a 6’3” attorney. With him, she experienced her first kiss. She was a teenage girl in the body of a 43-year-old man. The first time he stayed over, she was wearing a wig and didn’t know how she would get through the night with it on. When he reached up and took it off, she began to cry, and he held her. It was the first time she truly felt safe with another person.

They dated for a year and a half, until 2008, when Edward was deployed to Iraq. He was sent to Camp Bucca in Basra Province and put in command of 450 Ugandan military contractors, managing patrols and perimeter security. His bunkmate was a fellow soldier with whom he’d shared a room and office in Cuba. Off duty, Edward sat for hours on a camp stool, shielded by the lockers they’d placed between their beds for privacy. He watched DVDs or read emails, got lost in his thoughts or cried when it felt safe to let emotions overcome him. He was trapped. If he came out or was found out, he would lose his career and social standing. His friends took their gender and sexual desires for granted and had never had that freedom challenged. He knew they wouldn’t empathize.

Jennifer stopped in the middle of her story and asked me to imagine giving up my career and friends so that I could live the gender that felt natural to me. Would I suppress my desires in order to keep everything I’d built? Or could I make peace with walking away from a life of hard-earned skills and respect?

Month after month, sitting on the camp stool, Edward came to realize that the question was no longer whether he would transition, but how.

When he came home from Iraq, he resumed life as Jennifer and began taking hormones: spironolactone to depress testosterone levels and estradiol to introduce estrogen. Soon she was on an emotional roller coaster, pitched headlong into the intensity of a second puberty. Her chest grew itchy and then sore, her body hair and muscle mass diminishing as her skin softened.

In 2010, a year after starting hormones, she got word that Edward had been assigned to Kapisa Province to advise the French military’s training of the Afghan police. She was horrified. The “Middle World” had already been hard, and, on a few occasions, she, like many people in transition who suffer from isolation, had considered suicide. She was well on her way to a new life. She’d been removing her facial hair, and her breasts were so tender that once, during pre-deployment training, she had to wrap her chest with an ACE bandage so she could put on body armor.

In Afghanistan, she was Edward again, though he spent more time with the women on the base, as well as a bisexual male soldier he met through them — the only other LGBTQ person he encountered in his years of service. Eventually, he felt safe enough to tell them about Jennifer.

Edward’s work in the field involved overseeing police training, station construction, and distribution of pay to Afghan forces. He was almost killed by a rocket-propelled grenade during a meeting with village elders, and had to throw himself over a wall to escape. Weeks later, he would find himself lying in the garbage-strewn canal, ring back at attackers who had, just minutes before, shot and killed his guard — an experience Jennifer would struggle to recall clearly every time we spoke.

Two months after that attack, Edward returned stateside and led to resign. The process took longer than anticipated, because — as Jennifer explained to me — soldiers often want to quit after overseas deployment, and the Army tries to give them time to cool down and settle into a new job. But she was more than ready to leave Edward behind.

One morning, back in New Jersey, Jennifer picked up the phone to hear her mother crying on the other end. “What is this? Is this a joke?” she shouted in between sobs. Her mother had found Jennifer’s Facebook page. As more people in her life accepted her as Jennifer, the overlapping connections to Edward’s profile had pointed the way.

After several phone conversations, they met. It was the first time her mother saw Jennifer in person. Jennifer explained a life of covering up, of trying to be the son her parents wanted despite how unnatural it felt. Her mother listened intently, and, after Jennifer was done, she took her in her arms and held her as only a mother can. She told Jennifer she loved her. Later, when Jennifer was in the process of legally changing her name, she asked her mother to choose a new middle name for her. Her mother chose her own: Marie.

The court papers for the name change went through faster than the military discharge, and suddenly Jennifer’s driver’s license read Jennifer Marie Long and her military ID Sergeant Major Edward Long. While waiting for her discharge, she worked in battalion operations — “another one of those tough-guy divisions.” She was so far along in her transition now that she felt she was reverse cross-dressing in order to play the part.

Some of her co-workers started to notice things, making comments like, “Dude, don’t you have to fucking shave?” or “Doing too much landscaping there, pal?” in reference to her eyebrows.

Near the end of July, one of the guys saw the resemblance between Edward’s and Jennifer’s Facebook profile photographs. Overnight, Edward became the butt of jokes. Men he’d known for years turned their backs. His bunkmate from Cuba and Iraq wouldn’t speak to her. Two weeks later, the bureaucratic logjam cleared, and her retirement request was processed.

A sergeant major, being the highest non-commissioned rank, normally retires with ceremony and the gift of a sword or a plaque. But as Jennifer handed in her equipment, men who might once have taken a bullet for Edward ignored her.

The day she turned in her paperwork, she put on make-up, a dress, and a wig, and drove to Fort Dix. She was no longer willing to be Edward for their sake.

The woman in human resources was a civilian, and, because of Jennifer’s legal name change, agreed to process her out as Jennifer, giving her a retired-military ID card that read Jennifer Marie Long. She handed her a flag in a box.

“When I left that building that day, there were other peers and guys I knew in the halls. Nobody came to shake my hand. Nobody came to say goodbye. Nobody said, ‘Thanks for your service.’ I ended my career with a flag in a box.”

Life outside the military will not necessarily be safer for Jennifer than serving in Iraq or Afghanistan. Transgender women in the U.S. are about four times more at risk of violent death than cisgender women, with transgender murder rates having reportedly almost doubled in 2015. Transgender veterans face increased risks of homelessness and suicide. Because they are members of two of society’s more vulnerable groups, the challenges are compounded.

There is no way of knowing how many transgender soldiers were discharged from the military before the ban was repealed earlier this year. No record was kept of the number of expulsions, or the reasons given — whether medical or behavioral. Those who received less-than-honorable discharges — as was the case with gay service members prior to the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell — were disqualified from receiving tuition assistance and, in some cases, access to health care through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Individuals re-entering society with anything less than an honorable discharge on the papers they present to potential employers may be stigmatized and stymied for the rest of their lives, shadowed by questions about the reasons for the discharge.

Because she’d attained the rank of sergeant major and completed a number of tours, Jennifer was not at risk of losing her benefits. She believed that the military wouldn’t give anything other than an honorable discharge to a sergeant major, and, in her case, she was right.

As a veteran, she was finally able to speak openly. She worked with the American Civil Liberties Union on a New Jersey law that would protect the privacy of trans people by allowing birth certificates to be changed without being labeled “amended.” The bill passed the state assembly and senate, only to be vetoed by Governor Chris Christie. Jennifer then tried to amend her DD214, the military record of service used in civilian life when applying to college or jobs. With the ACLU’s help, she and another veteran requested that their DD214 forms be updated to reflect their genders. Traditionally, the review board would only change the form in the event that an entry or omission was erroneous or unjust. The board decided that neither was the case and denied the request. However, Francine Blackmon, deputy assistant secretary of the Army, overturned the vote, based, in part, on Jennifer’s explanation of how much the document affects her life.

“I just wanted it to reflect who I am now,” Jennifer told me, “so that it honors me and my service, and I don’t have to tell the story of being transgender to everyone.” TAVA, the Transgender American Veterans Association, now offers instruction sheets and guidance for changing the DD214 on the basis that the presence of an old name reveals a person’s transgender status, and therefore constitutes an injustice.

During her transition, Jennifer completed a college degree in finance, and, after her discharge, she became a financial advisor. In 2013, she joined her local VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars). Most of the members had done a tour or two. She was among the few career soldiers, and, in 2014, she was elected the post’s first female commander in its 91-year history. No one at the VFW knew she was transgender — until a local paper ran an article about her activism and transition. She was apprehensive that her VFW peers might turn on her, but the veterans’ response was markedly different from that of her fellow soldiers on active duty. A few veterans said they were shocked to learn she hadn’t always been a woman, but they already had an established relationship with Jennifer, and she had earned their respect. They had never known Edward, whereas her colleagues in the military had known only Edward, and may have felt lied to or betrayed by him. Jennifer’s experience with the VFW suggests that, once people know a transgender individual in their target gender and have worked with them, they are more likely to accept them. She has since been elected VFW district commander and re-elected to a third term as post commander.

Media and online interactions can also create a sense of familiarity, and society’s changing attitudes toward LGBTQ people may be fueled, in part, by media-generated empathy. The caricature of the drag queen has faded, and not conforming to one’s birth gender is gaining wider acceptance in our culture. Transgender characters are now featured in young adult novels and television series. In 2013, former Navy SEAL Kristin Beck published a memoir about her transition, and, in 2015, Olympic gold medalist Bruce Jenner came out as Caitlyn Jenner. Progress in LGBTQ rights helped pave the way for these changes: the 2011 repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, and the legal battles and activism leading to the 2015 Supreme Court ruling that same-sex marriage is a constitutional right.

In July 2015, a year before the military ban on transgender people was lifted, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter had announced a de facto moratorium on judgments against transgender soldiers. Questions abounded: Could genetic females who transitioned to men serve in the infantry, which was open only to men? Could biological males who identified as women remain in the infantry? That December, when Carter declared all combat roles available to women, such questions became irrelevant; the path for transgender soldiers to serve in all branches of the military had been cleared.

Carter’s June 30th announcement that transgender people can serve openly was informed by a RAND Corporation report commissioned by the Department of Defense, which summarized the policies of the United Kingdom, Canada, Israel, and Australia, all of which allow transgender soldiers to serve openly. The four have only slight differences in approach. In Australia, for instance, after a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria, soldiers may begin a “social transition,” during which time they live publicly as the target gender and begin using the appropriate name, identification cards, uniforms, housing, showers, and restrooms.

The report also looked to foreign militaries to help determine the effect transgender soldiers might have on group cohesion, citing a longstanding concern that “if service members discover that a member of their unit is transgender, this could inhibit bonding within the unit, which, in turn, would reduce operational readiness.” But no such problems with cohesion have been reported in studies done by foreign militaries, according to RAND, and similar concerns regarding gay and lesbian personnel have not been borne out since the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

Under the military’s new policy, recruits will be required to wait 18 months after transitioning to ensure stability in their new gender. The RAND report estimates that 29 to 129 transgender soldiers will seek transition-related treatment each year, including sex re-assignment surgery. It cites “a consensus among clinicians and their professional organizations that transition-related treatment with hormones or surgery constitutes necessary health care,” either to diminish suffering or to help achieve self-actualization. The military has committed to paying these costs, which the report evaluates as minimal: only $2.4 to $8.4 million annually from the roughly $50 billion budget of the Defense Health Agency, which provides health care to all branches of the military and their families. The same treatment may also become available through the Department of Veterans Affairs and be provided for the first time by VA hospitals.

Had this sea change in the military happened earlier, Jennifer most certainly would have been spared years of stress, including those long hours on the camp stool in Iraq, trying to determine how to be herself without losing everything she had worked for. If the stigma against trans soldiers had not been institutionalized, she might have continued to provide her expertise to the military or been able to maintain the friendships she had built there, possibly generating even higher levels of cohesion and readiness among her unit. She would have had the opportunity to show that patriotism and leadership do not require being a tough guy, and that no gender identity is an impediment to being an exceptional and exceptionally honorable soldier.

The Department of Defense released a document, effective October 1st, 2016, that provides information on how to integrate and support transgender soldiers and those who are transitioning. It will also need to address whether those who received less-than-honorable discharges can have their records updated and benefits re-instated — as has been done for some gay and lesbian veterans since the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. (A Department of Defense spokesman said those policies are currently being worked out.) Jennifer points out that progress also needs to be made at VA hospitals, where she has had to educate nurses and doctors about transgender medical issues and even had to explain to them why she didn’t need a Pap smear.

The military’s new transgender policy hasn’t been without pushback. Just as the Internet has opened our eyes to the humanity of the transgender Americans living alongside us — and has taught us that trans people have existed throughout history — the online world has also given voice to conservative groups threatened by change. It’s difficult for some to understand how the military, largely perceived as a bastion of conservatism, could take such a significant step toward inclusion. The Internet creates echo chambers and silos in which people reinforce each others’ prejudices and become comfortable voicing them, galvanizing a hate that might explain the increase in violence against transgender people. While millions of cisgender Americans have learned to accept transgender people, transgender people have become lightning rods for conservative rage. Following North Carolina’s example, many states are challenging the federal government’s recent expansion of transgender rights. There are even reports of vigilantes who watch over bathrooms and harass people who appear not to conform to gender norms.

Jennifer believes that, ultimately, the military’s decision will move social acceptance forward and that the military may even be ahead of much of the private sector in terms of its treatment of transgender people. She also thinks that the new policies will allow the military to retain more talent. “I did the job well, on hormones, in a foreign country,” she says of her tour in Afghanistan. “We are one of 19 nations now that have open transgender service,” she is quick to point out. “We are not blazing the trail.”

But Jennifer is. Increasingly celebrated for her advocacy, she has received the ACLU Torchbearer Award for Activism and has been invited to speak for Transgender Awareness Day at Bergen Community College and for LGBT Month at Picatinny Arsenal, one of the country’s oldest military installations. And yet, as the commander of her VFW post, she traveled to North Carolina earlier this year for a VFW convention, where, despite all she has endured and achieved as a transgender soldier and civilian, she had to risk arrest and harassment for using the bathroom corresponding to her gender.