In the early days of his presidency, during a visit to Prague’s Hradčany Square, Barack Obama launched what observers saw as a centerpiece of his foreign policy: a doctrine for a nuclear free world. “The Cold War has disappeared but thousands of those weapons have not,” President Obama announced, pointing out the paradoxical twist of the modern nuclear dilemma—as the threat of global nuclear war has subsided, the risk of a singular nuclear attack has only intensified.

“More nations have acquired these weapons. Testing has continued. Black market trade in nuclear secrets and nuclear materials abound. The technology to build a bomb has spread. Terrorists are determined to buy, build, or steal one,” Obama continued. “Our efforts to contain these dangers are centered on a global non-proliferation regime, but as more people and nations break the rules, we could reach the point where the center cannot hold.”

Taken in the context of his other campaign promises—the closure of Guantanamo, (which has only truly blossomed in the twilight hours of his presidency) and the end of the two costly wars he inherited—Obama’s nuclear promise seemed both heroic and unimpeachable, especially given its tacit support by past foreign policy luminaries. Mere months after his Prague address, Obama was awarded the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize—a symbolic endorsement of his nascent doctrine—with the Nobel Committee specifically citing the “special importance to Obama’s vision of and work for a world without nuclear weapons.” Obama used the moment to make the case for “just war” in the modern geopolitical stage: “We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations—acting individually or in concert—will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified.”

The minute things went south with Russia, the United States went back on it’s promise to work toward a nuclear-free world.

But six years later, in a book released last year, the former Pulitzer director wrote that the prize “didn’t have the desired effect” of helping to catalyze such change. He’s not wrong. The Obama administration certainly made historic steps in unifying the international community on the issue of nuclear weapons, particularly the historic nuclear deal between Iran and the P5+1 countries. But at the same time, despite promises to pursue new restrictions on nuclear technology and decrease the nation’s nuclear stockpile, the American military’s nuclear posture has remained largely static. Obama’s dream of non-proliferation is, it seems, long dead.

First, consider the efficacy of the historic Iranian nuclear deal signed in 2015. While Republican opponents (and Israel) remain dead-set on dismantling an agreement that would essentially prevent Iran from ever building a bomb, the deal has been branded a foreign policy coup for the Obama administration. With the deal, Obama managed to decrease military and diplomatic tensions in line with his administration’s continued policy of engagement with the Iranian regime. As of now, Iran appears to be in compliance, and as a result has received much-awaited sanctions relief. This, in turn, helped deliver a sweeping political victory of moderates and reformers in Iran’s February elections, “seen as an endorsement of the deal [President] Rouhani sealed with six world powers,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

This affirmation has, per the Los Angeles Times, long-term repercussions for Iran’s internal politics:

Hard-liners who oppose the nuclear deal also suffered significant setbacks in a parallel election taking place for the Assembly of Experts, an 88-member panel of Islamic jurists who are supposed to select the clerical supreme leader, the most powerful figure in Iran’s hybrid political system.

Two of the most conservative members of the assembly, Mohammad Yazdi and Mesbah Yazdi, were not reelected to their posts following a social-media campaign to oust hard-liners. The assembly election is being closely watched because its members could choose the successor to the current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is 77 and in declining health.

But despite this, the Obama administration continues to face challenges with the second biggest nuclear threat in the world: Russia, the country with an enormous (and insecure) nuclear stockpile.

Given the ubiquity of fissile material available on the black market in former Soviet nations, Russia is ground zero for proliferation. Things hit a high point for Obama in 2010: There were the negotiations with Russia to form the 2010 New START agreement (which was created to slash both countries’ nuclear arsenals), and his efforts to secure a 47-nation agreement to help secure loose nuclear materials within the next four years at the inaugural Nuclear Security Summit in 2010.

The intervening years, however, have not been good to the administration’s initial successes: From the start, Russia repeatedly ignored continued proposals from the Pentagon on implementing the terms of the New START treaty, and recently pulled out of attending this year’s Nuclear Security Summit in Washington in what’s been widely seen as yet another blow to the Obama administration’s nuclear efforts.

Vladimir Putin’s return to power and Russia’s increasing involvement in Syria and the Ukraine (plus the annexation of Crimea) have only served to ratchet up tensions between Russia and the West. The downing of a Russian warplane by a North Atlantic Treaty Organization jet in November certainly didn’t help things; Russia’s foreign minister even threatened “world war” if the West ever sent ground troops into Syria to combat ISIS. “The most fundamental game changer is Putin’s invasion of Ukraine,” former Obama nuclear adviser Gary Samore told the New York Times in 2014. “That has made any measure to reduce the stockpile unilaterally politically impossible.”

The administration’s relationship to the world’s biggest source of loose nuclear materials is at its lowest point in recent memory, a development that doesn’t just effectively invalidate the New START agreement but has actually led to a slight uptick in operational nuclear warheads worldwide. The minute things went south with Russia, the United States went back on its promise to work toward a nuclear-free world.

It’s this tension that has forced Obama to break America’s nuclear pledge to the world. With the release of the Pentagon’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, the Department of Defense had ostensibly committed itself to “a multilateral effort to limit, reduce, and eventually eliminate all nuclear weapons,” seemingly in line with Obama’s nuclear-free doctrine laid out in his Nobel speech and solidified in the Nuclear Security Summit and New START agreements. The U.S., the document promised, “will not develop new nuclear warheads,” and efforts to maintain and update the government’s existing nuclear arsenal “will use only nuclear components based on previously tested designs, and will not support new military missions or provide new military capabilities.” The nuclear umbrella that’s implicitly backed Western hegemony over international affairs would grow no further.

But Obama’s nuclear budget has swollen in recent years. In his proposed $620.9 billion defense budget for 2017, Obama called for a $1.8 billion increase in nuclear spending “to overhaul the country’s aging nuclear bombers, missiles, submarines and other systems,” according to Reuters. The budget request allocates millions in taxpayer dollars for the development of a new nuclear-tipped cruise missile, replacing the military’s arsenal of air-launched missiles, and almost doubling the military’s nuclear cruise missile collection to nearly 1,000 missiles—all initiatives seemingly in contradiction to the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review and Obama’s early-term non-proliferation rhetoric. And this isn’t a sudden change, but the latest jump in nuclear arms spending at the cost of non-proliferation efforts since 2011, according to reporting from Mother Jones.

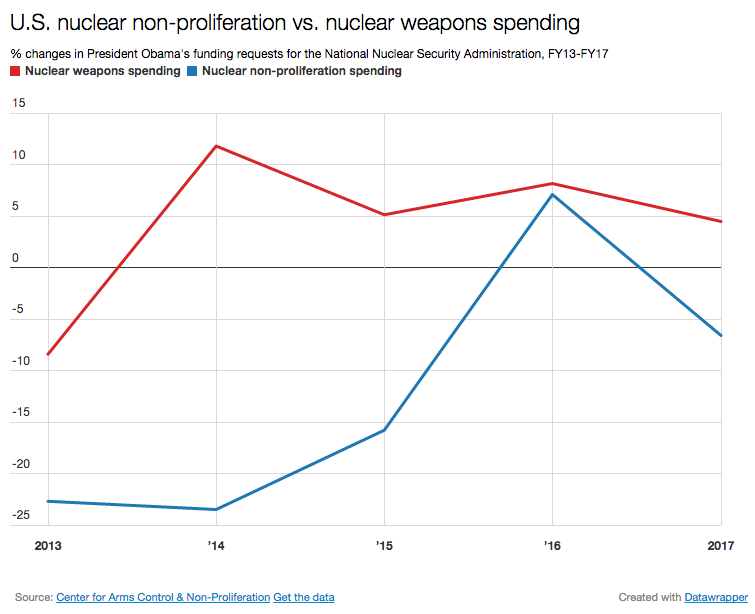

Data from the Center for Arms Control & Non-Proliferation shows a steady increase in nuclear spending in Obama’s defense budget since 2012, all while non-proliferation spending has been on the decline:

“What’s more problematic is the decrease in nuclear nonproliferation programs by over $100 million,” Global Zero executive director Derek Johnson wrote for the Hill. “These are highly functional programs dedicated to keeping the world’s nearly 16,000 nuclear weapons out of terrorist hands and locking down vulnerable nuclear material…. In a global security climate traumatized by the rise of ISIS, decreasing nuclear nonproliferation programs seems a dangerously misguided trade-off.”

Johnson’s not wrong: In 2014, ISIS seized a cache of 88 pounds of uranium compounds in Iraq, and a June 2015 report indicated that ISIS had already gathered enough nuclear material to build a dirty bomb. It’s vaguely ironic, considering Obama couched his nuclear-free plea of 2009 in the closure of Cold War-era geopolitics. The U.S. has conducted 15 long-range missile tests since 2011 as reminders to Russia and North Korea—even though the threat of a nuclear ISIS is probably more dangerous than any Iranian centrifuge ever could be.

In retrospect, we should have known better. In his Nobel address, Obama didn’t just lay out a doctrine that would define his foreign policy; he delivered a masterclass in doublespeak, using the validation of his campaign rhetoric of a utopian, nuclear-free world while recognizing the permanent reality of modern realpolitik and nuclear terrorism. And while the promise of a nuclear-free world is an inherently naïve proposition, his doctrine of just war was prescient: Obama has expanded the field of battle against terrorism with a deadly drone program while in turn touching off a “modernization” arms race with Russia, as the Intercept puts it.

The administration is trumpeting its success with Iran—and with good reason—but Obama’s record on nuclear weapons is hardly an affirmation of his Nobel Peace Prize. The dream of a world without nukes, it turns out, was always really just that: a dream, and nothing more.