California is now experiencing its worst storm yet — with the potential to reshape its history.

By Eric Holthaus

A rainbow is made by spray from water coming down the damaged main spillway of the Oroville Dam on February 14th, 2017, in Oroville, California. (Photo: Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images)

Amid the wettest start to a rainy season in state history, California is now experiencing its worst storm yet—with the potential to reshape its history.

An atmospheric river — a narrow band of tropical moisture — is taking aim at the central California coast on Monday and Tuesday, and providing a textbook meteorological scenario for major flooding. The National Weather Service office in Sacramento used dire language to describe the threat, urging residents to be prepared to evacuate with less than 15 minutes notice and warned of flooding unseen for “many years” in some places. More than a foot of rain is expected over a 36-hour period in higher elevations.

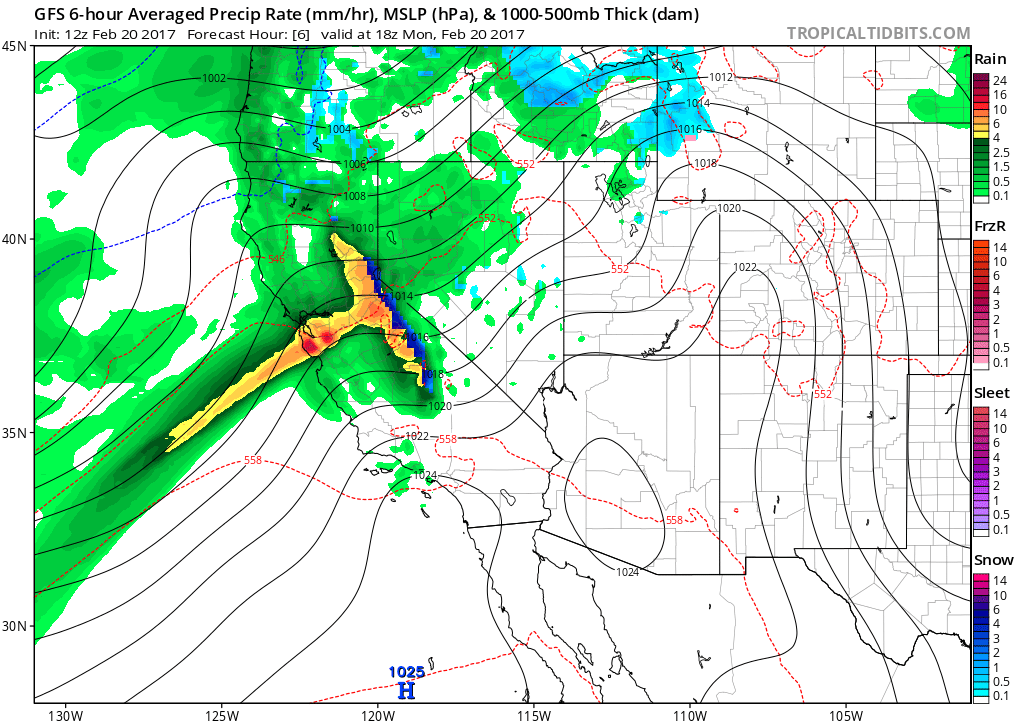

A weather model projection of the atmospheric river, as of Monday evening, with tropical moisture creating heavy rainfall as it hits the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

As of Monday morning, a cascade of flood warnings are in effect for the Bay Area and the Central Valley, as heavy rains reach the coastline. Dozens of lightning strikes have been detected offshore, and numerous landslides are being reported. A weather station near Big Sur, on the central coast of California, picked up more than an inch of rain in just an hour — a rainfall intensity more typical of a heavy tropical thunderstorm.

By Monday evening, damaging winds nearing hurricane force could spread across much of the central and northern part of the state, prompting the National Weather Service to warn of “long-lasting” power outages for thousands of households.

Heavy rains will continue on Tuesday, at which point serious problems could begin to emerge. The fragile Oroville Dam will again be tested, but dozens of other dams — like the one at Don Pedro Reservoir near Modesto — are also nearing capacity statewide and planning emergency contingencies.

By late Tuesday, the San Joaquin River — the main hydrologic thoroughfare of the vast Central Valley — is expected to exceed a level not seen since 1997, and then keep rising the rest of the week. The river is already in “danger” stage — the stage above flood stage when critical levees could begin to become compromised.

California’s levee network constrains the flow of water as it leaves the mountains of the Sierra Nevada and makes its way toward the Delta region near Sacramento. Overwhelming this system could bring a flood that, according to a study from the United States Geological Survey in 2011, could inundate hundreds of square miles and cost hundreds of billions of dollars, knocking out the water supply for two-thirds of Californians in the process; it would be the worst disaster in American history. That study, referred to as the “ARkStorm” scenario, was designed to anticipate the impact of a flood with an expected return period of about 300 years, similar to the one the region last experienced in 1862. A 2011 New York Times Magazine article about that scenario used the word “megaflood.”

Weather models on Sunday showed that rainfall intensity on Monday near the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta could briefly reach levels not expected more than once a century — or even once per millennium if the slow-moving atmospheric river stalls completely, a scenario consistent with past levee breaches.

Making the impact of this storm even worse is the fact that Northern California has already racked up more than double the amount of rain it typically receives between October and late February. The rainy season is running about a month ahead of the previous record-setting pace set in 1983 — a rate not seen in at least a century of record-keeping. San Francisco has already eclipsed the total it typically receives in an entire “normal” rainy season in less than half the normal time.

The ARkStorm scenario was constructed without taking into account the effects of climate change, which helps to make atmospheric rivers more intense. A warmer atmosphere increases the rate of evaporation and causes more precipitation to fall as rain instead of snow. In California, the intensity of atmospheric rivers could double or triple by the end of the century.

Should this week’s atmospheric river morph into a megaflood — and it is still unlikely, though not impossible that it will do so — it will mean California has quickly transitioned from milliennial-scale drought to a millennial-scale deluge. Welcome to climate change.