Austria’s mountain farm outposts are cultural and economic strongholds in uncertain economic and environmental times.

By Bob Berwyn

The centuries-old Herrenalm is nestled in a deep hollow among the highest peaks of the eastern Alps. At midday, the cattle are scattered among higher dispersed pastures, but signs of grazing are evident in the terraced hillside toward the upper right in the photo. (Photos:

Bob Berwyn)

The second installment in a three-part series on sustainable mountain agriculture in Austria. Read the first installment here.

There’s no sign of a drought or heatwave as we hike through through lush green forest along Taglesbach up toward the Herrenalm, one of the oldest mountain grazing outposts in this eastern spur of the Alps, where the Austrian mountains jut into a crescent of the Danube valley and toward the high Balkan plains beyond.

If anything, frequent rains have dampened the hay harvest, with farmers speeding to make the cut and bundle the piles of grass before it gets moldy. But not long ago, in the summer of 2014, an unprecedented month-long heatwave browned the grass in mid-summer, as temperatures across Austria soared to new records, in line with a global trend that saw the Earth’s average annual temperature spike to a new high for the second year in a row—and dangerously near the 1.5 degree Celsius mark set by the Paris climate agreement as the target to avoid catastrophic climate change effects.

A lone maple tree stands in the pastures of the Herrenalm.

Too wet, too hot, too dry follows a global trend toward more climate extremes. Climate scientists agree that a warmer atmosphere will bring more intense rains, simply because warm air can hold more moisture. While the existing data record is too short to be conclusive, emerging studies are documenting the trend toward more extreme rainfall events in the Austrian Alps. Consequences include giant rocks and mudslides that damage infrastructure.

In the forest-field quilt of the Austrian mountains, the growing and breeding season is short. Timing is everything, and there are signs that the clock has been skewed — the birds and bees are out of sync.

Other studies have shown that droughts may be getting more extreme because of a wavier jet stream (caused by melting Arctic ice) that leaves weather patterns stuck in one place. And there’s little doubt that warmer temperatures will exacerbate any dry spells. The warmer it gets, the more water goes from the soil back to the air, and the more the plants drink.

Some climate change impacts to the Earth are incredibly obvious, like glaciers that have been steadily retreating 100 meters or more each year in recent decades. Other changes are more subtle, playing out on a micro scale within larger landscapes. That’s because we’re in an era of rapid climate change that has shifted seasons so fast that plants, bugs, and even birds can’t keep up.

Alpine meadows are reservoirs of biodiversity.

In habitats like the forest-field quilt of the Austrian mountains, the growing and breeding season is short. Timing is everything, and there are signs that the clock has been skewed—the birds and bees are out of sync.

Long-term monitoring at mountain research stations on several continents says that, because of global warming, the snow is melting earlier, with some plants flowering up to four weeks earlier than they did 40 to 50 years ago. The problem is that there are still cold snaps later in the season that damage the premature buds and flowers. Insects that rely on the nectar and pollen don’t find what they need, and birds that feed on the insects during nesting season also go hungry.

This type of science is painstaking. One study in Colorado analyzed 30 years’ worth of data on when certain flowers bloom and how that affects migratory hummingbirds. In another project, biologists looked at a similar link between breeding butterflies and a very specific species of mountain aster it depends on.

Taglesbach cascades and mountain bluebells along the trail to the Herrenalm.

Yellow globeflower, in the buttercup family, and alpine heather, growing in the meadows around the Herrenalm.

It all adds up to serious challenges for the sustainability of these ecosystems, including the pastures of the Herrenalm, at 1,327 meters near the town of Lunz am See. And it matters because the seasonal alpine pastures, known in Austria as Alms, are deeply enmeshed in the cultural and economic fabric of the country, part of its folklore in song and story, and part of its economy, down to the bucolic mountain landscapes depicted on nearly every packet of cheese, milk, or butter.

In the early days, it wasn’t just the meat and dairy production that was important. The short-lived and fragrantly bitter flowering herbs like gentian and arnica were sought as medicinal ingredients good for infused alcoholic tinctures, skin salves, and strong brandy. And the hay from the highest meadows was crucial winter feed for the cattle in the barns — so much so that there was a specific guild of particularly sure-footed mountain dwellers who specialized in scything stands of tall grass from the nearly vertical crevices among the craggy peaks.

Archaeologists say there are signs that human beings have grazed cattle around the Herrenalm since the Bronze Age, and, when we reach the stone hut tucked into the green mountain valley, it feels like we’ve arrived at a little mountain oasis. Along with the burbling water in the troughs out front, we hear an accordion and singing. The cattle are fat and happy in the verdant pastures; inside, friends gather to share songs and jugs of local cider and white wine.

I soon find out there’s more than one use for a cowbell. The herders may use them to track errant cows through a misty forest, but, when I ring the big one hanging over the kitchen table, the posse at the table roars and laughs — the person who rings that bell, it turns out, is signaling his willingness to buy another round, So Lisi, the innkeeper, pulls the plug on a new two-liter jug of cider and the accordion player starts another tune.

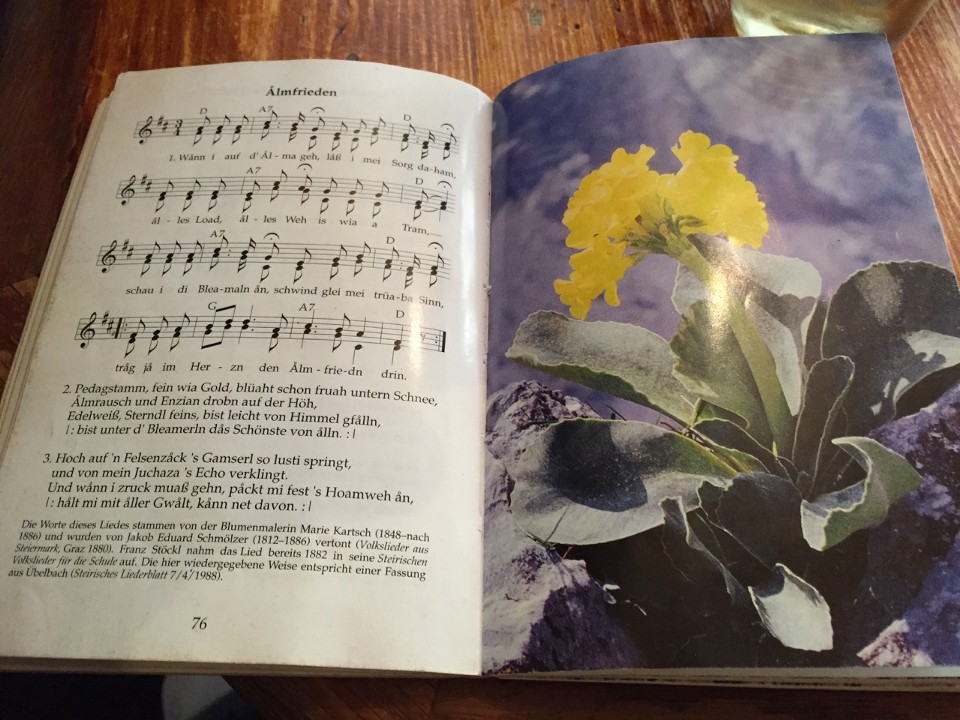

Many of the songs are about companionship and the beauty and spirituality of the mountain environment. The lyrics to the song Almfrieden includes a natural history observation about a type of yellow primrose that often blooms in early spring while it’s still surrounded by snow, and describes the joy of finding rare Edelweiss wildflowers. But the climatic shifts from global warming could push some of these traditional native flowers off the top of the mountains.

“We come up here to feel the mountains and to be with our friends and make music,” the accordion player tells me between songs. “We leave our work and out troubles in the valley and enjoy the spirit of the mountains.”

Mountain songbook.

Those shared experiences and values create community, but there’s an economic aspect to Alm agriculture too: The valley cattle farmers often pool their resources to manage the summer highland pastures for the benefit of the community herd. That also helps build community ties and helps the small farms compete with larger feedlot operations in the flatlands.

But centralization of food production, including beef and dairy products, is a serious threat to the sustainability of mountain agriculture, according to University of Innsbruck professor Markus Schermer. Already, there is a documented trend called Bauernsterben (farmer die-off); a lot of small mountain farmers have given up, in part because of the new climate challenges, but also partly in response to economic policies that encourage development of ever-larger feedlot-based operations in areas closer to transportation arteries and urban markets, he says, describing a divide in the food production system as “food from nowhere” versus “food from somewhere.”

“We have to find a different pattern of growth, a different approach to the agriculture of the middle, not to lose it to corporate farming,” Schermer says.

That’s not to say that large-scale food production has been entirely bad for the country. Along with many other producing and consuming countries, Austria has benefited from globalized large-scale trade, exporting meat and dairy to China, for example. But Schermer wonders what might happen if China were to stop importing from Austria.

Keeping small-scale agriculture alive has further, intrinsic value that can be hard to measure: the value of healthy cows munching on clean food without chemical additives, the direct connection between humans and their food. Supporting sustainable, localized food production stabilizes the food system and makes it more secure, thereby helping the overall economy.

“We need values-based supply chains, with personal, long-term relationships along the chain, and the distribution of these different values in a fair way. We should introduce into the marketing system a different power gradient,” Schermer says.

That doesn’t even require a radical transformation of the economic system, he explains. There are already thriving examples of local agricultural co-ops creating regionally valued brands. Supporting those brands can even benefit bigger players, as small-scale organic farmers team up with big regional supermarket chains to highlight local products.

Herrenalm caretaker Franz Pöchacker (left) explains how he uses his walking stick to track the more than 100 cows that he’s been entrusted with using a series of marks.

Sustainable mountain agriculture is a win-win in the long term, ensuring local food security in uncertain global times. The high mountain pastures will also be more important because global warming is projected to lead to more drought and decrease productivity at lower elevations by the second half of the century, especially in southeastern Austria. This economic and environmental puzzle is complex, but a scientific and grassroots movement is emerging to tackle the challenge.

The simple and rustic furnishings at the Herrenalm help visitors escape the information and consumption overload of the 21st century.

After a good night sleep in the loft, a farmhouse breakfast.

Life at the Herrenalm goes beyond herding cattle in the alpine pastures. It’s a focal point for social and cultural life and helps keep mountain traditions alive.

This story was made possible in part with support from the Earth Journalism Network& Internews.