Legitimacy is for losers.

This spring, the U.S. Supreme Court will announce one of its most important decisions since its ruling in Bush v. Gore. The decision in the cases — all having to do with the constitutionality of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act — likely will have vast political consequences, perhaps well beyond health care itself. The court will also decide a number of other blockbuster cases in 2012, from the highly polarized Arizona immigration legislation (whether people can be stopped by the police and interrogated about their immigration status) to the question of whether 14-year-olds convicted of heinous crimes can be incarcerated for the rest of their lives without any possibility of parole.

If the smear of partisan decision-making tars the unelected U.S. Supreme Court after these decisions, the fundamental legitimacy of the institution may become precarious.

Why exactly is legitimacy so important?

Legitimacy means that an institution has the right to make decisions, and, because those decisions are fairly, impartially, and procedurally properly made, citizens are under the obligation to accept those outcomes, even when they disagree with them. So, in this sense, legitimacy is for losers — those on the losing side of the issues the Supreme Court decides.

With so many highly politicized cases looming, all decided within months of what will undoubtedly be a bitterly contested presidential election, many legal observers fear for the institutional legitimacy of the Supreme Court. Even those legal scholars not in love with the court as an institution recognize that, without popular legitimacy, the U.S. Supreme Court is a precarious, vulnerable, and potentially impotent political institution.

Can the Supreme Court “get away with” a decision on health care without suffering permanent damage to the institution? Using the evidence on the court’s legitimacy based on surveys I made last year, the answer is probably yes.

I should be clear about this analysis — I am not claiming liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, differ little on how they judge the day-to-day performance of the Supreme Court or in how they evaluate any given court ruling — such as the forthcoming health-care decision. Liberals tend to judge the Supreme Court as too conservative; conservatives think it too liberal.

But when it comes to the fundamental legitimacy of the institution — whether its decisions, even its disagreeable decisions, ought to be accepted — Democrats differ little from Republicans, just as liberals hold about the same views as conservatives. Judicial legitimacy in the contemporary U.S. is not bundled up with partisanship and ideology.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

But let’s examine the basis of concerns, which goes something like this: the court’s legitimacy is best sustained through the belief that its methods of policymaking are somehow not political, that the court is not “just another political institution.”

That the Supreme Court is widely perceived as different from other political institutions is deemed by many to be essential to the maintenance of the institution’s legitimacy.

As Justice Potter Stewart has written: “A basic change in the law upon a ground no firmer than a change in our membership invites the popular misconception that this institution is little different from the two political branches of the Government. No misconception could do more lasting injury to this Court and to the system of law which it is our abiding mission to serve.”

Under normal conditions, few pay close attention to the Supreme Court, and the institution seems to profit from its obscurity (one argument for not televising the court’s oral arguments). When people do pay attention, the danger always exists that they will learn that the court is just another political institution, that the justices are no more immune to partisan and ideological influences than any other public officials.

And if they do not learn this by themselves, enterprising political elites from the losing side will undoubtedly seek to teach that lesson to the American people.

As Adam Liptak has observed in The New York Times: “Should a bare majority of justices composed solely of the court’s Republican-appointed members strike down a Democratic president’s signature legislative achievement, the public perception of the court may be altered.”

Moreover, “… some scholars are already wondering how much damage, if any, a party-line ruling striking down the law would do to the court’s prestige, authority and legitimacy.”

Regarding the current Supreme Court, several facts buttress these scholars’ worries. First, this court’s decisions are rarely unanimous, and at least some are bitterly divided. Second, the court is closely balanced between a quite conservative bloc and a relatively more liberal bloc.

Finally — and perhaps of greatest importance — the ideological divisions on the current court perfectly line up with partisanship. That is, for the first time in many decades, all Democrats on the court are relatively liberal, and all Republicans are relatively conservative. (If this seems self-evident, remember that Earl Warren, widely seen as a liberal, was a staunch Republican.)

Meanwhile, the health-care litigation itself seems to many to be inherently politicized and partisan, and in rulings from lower appellate courts, most Republican judges have found the legislation unconstitutional, while most Democratic judges have not.

Thus, the Democratic legislation on health care could quite easily be ruled unconstitutional by the votes of five Republican justices, over the objections of the four Democratic justices on the bench. Under this configuration of justices, the argument that ideology divides the current court cannot be distinguished from the claim that partisanship divides the current court.

The American people can stomach principled ideological disagreements, but they hate partisanship in law and politics. Partisanship poisons.

The court’s legitimacy depends overwhelmingly on the American people perceiving its decisions to be principled, even if ideological, and not a reflection of the partisan bickering so characteristic of the other branches of America’s government.

Within the poisonous context of a highly polarized presidential election — and the already revealed willingness of some if not most of the Republican candidates to challenge the legitimacy of the Supreme Court — a health-care decision decided by five Republican justices against four Democratic judges will be so easy to caricature, that it is a sure bet that many politicians will not shirk from attacking the court on partisan terms. And President Obama has himself also shown only limited restraint in challenging the Supreme Court for its decisions (e.g., on Citizens United). It is little wonder that legal observers see the court as quite vulnerable.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s effort to pack the court in the 1930s is a textbook example of the power of legitimacy within the context of high stakes political disputes.

Enraged by numerous Supreme Court rulings against the constitutionality of his New Deal legislation, Roosevelt attempted to “pack” the court with new nominees favorable to his legislative program. Public opinion polling was in its infancy in the 1930s, but many scholars nonetheless believe that the court’s “reservoir of goodwill” — its store of institutional legitimacy — rendered Roosevelt’s scheme unpalatable to a large segment of the public.

We will never know for certain whether institutional legitimacy saved the court — the court changed course in its rulings before the issue came to a head and consequently FDR abandoned his court-packing proposal — but legitimacy as a form of political capital is widely recognized by scholars and judges as crucial to protecting an institution that is tasked with guarding against abuses perpetrated by the majority.

Bush v. Gore, in which George Bush was awarded the presidential election of 2000, was also a classic case of power of institutional legitimacy. To the astonishment of many, the Supreme Court’s decisive intervention in the election was accepted by nearly all, Republicans and Democrats alike, and, if anything, the Supreme Court augmented its legitimacy through this decision, rather than subtracting from it.

The key issue from the perspective of legitimacy theory is whether those who lose on the health-care decision will accept their loss, and, more specifically whether they will be willing to respond favorably to attacks on the court as an institution. Is the Supreme Court’s supply of legitimacy sufficient to ride it through the storm its rulings on health care and other highly politicized and polarized legal issues will undoubtedly create?

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

For years now, social scientists have worked hard on developing empirical indicators of the level of popular legitimacy enjoyed by political institutions. They conceptualize legitimacy as akin to loyalty — the willingness to stand by an institution even when one is dissatisfied with its decisions — and so have developed an accepted set of propositions that can be used to measure to the Supreme Court’s legitimacy.

My 2011 survey of a nationally representative sample of Americans — supported by the Weidenbaum Center at Washington University in St. Louis — used responses to these seven statements to measure the respondent’s willingness to extend legitimacy to the U.S. Supreme Court. According to the replies to these queries, most legitimacy was discovered on the statement that: “If the U.S. Supreme Court started making a lot of decisions that most people disagree with, it might be better to do away with the Supreme Court altogether” — 70 percent disagreed that the court ought to be abolished. At the same time, however, only 28 percent disagreed that “The U.S. Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics.”

Across the set of seven responses, the median number of supportive replies was three; the median number of non-supportive answers is two. Nearly 54 percent of the respondents gave more supportive replies than nonsupportive replies (with another 6 percent giving an equal number of supportive and nonsupportive answers to our questions).

Thus, support for the Supreme Court is not consensual, but it is strong — and it is no doubt stronger than support for any other political institution in the U.S. today.

A key question for 2012 is whether there is partisan advantage in attacking the Supreme Court. The Republican candidates are already stumbling over themselves to question the authority of the Supreme Court, and Obama has not been reticent about criticizing the court for its decisions. Will attacks on the court resonate with partisans of different stripes?

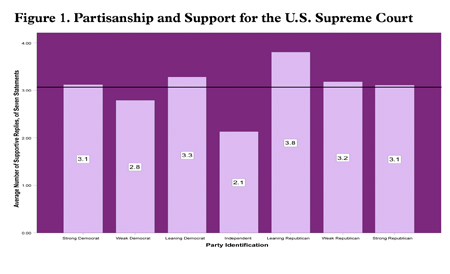

To investigate this possibility, the graphic above shows the relationship between the respondents’ party identifications and their levels of support for the Supreme Court (as represented by the number of supportive replies given to the seven propositions put to the respondents).

This figure is remarkable in documenting the near complete absence of a relationship. Knowing one’s party attachment provides practically no purchase on predicting how one feels about the Supreme Court.

Compare, for example, the responses of those describing themselves as “strong Democrats” with those who are “strong Republicans.” No difference whatsoever exists between these strong partisans — both groups score right at the average for Americans as a whole (depicted by the horizontal line in the graph).

Moreover, the differences across the three types of Democratic identifications are no statistically significant, while the difference across Republicans just barely achieves statistical significance and are due to the relatively strong support for the court among a single group — those independents who lean toward the Republicans.

And, to reinforce a conventional finding from research on partisanship, those who eschew any party attachment (“independent independents”) are lower in support for the Supreme Court but mainly because this group is characterized by the largest proportion of respondents saying they have no opinion about the court questions about which they were asked. Independents are rarely too informed to be able to make clear choices; they are usually too uniformed to be able to formulate an opinion.

According to these data, attacks on the Supreme Court are unlikely to generate partisan advantages. Attitudes toward the court’s legitimacy are simply not connected to partisanship, at least among ordinary Americans.

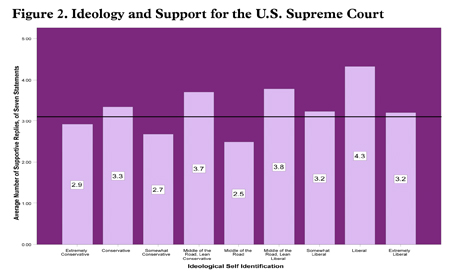

But what about ideological differences in how Americans judge the Supreme Court? The graphic below depicts the relationship between institutional support and the ideological identifications of those interviewed in the survey.

Statistically, a slightly stronger relationship exists with ideology as compared to partisanship, and the differences shown in Figure 2 do in fact achieve statistical significance.

However, the relationship depicted is not a simple linear, left-right difference. Those who are extremely conservative support the court at roughly the same level as those who are extremely liberal. Generally, those who think of themselves as some variety of liberal are slightly more supportive of the court as an institution than conservatives; however, the relationship is quite timid. A politician attacking the Supreme Court would generate only a small ideological advantage among conservatives.

Consider the new arithmetic of judicial legitimacy.

A 2011 Time Abt SRBI poll (conducted at roughly the same time as my survey) indicates that 56 percent of the American people believe the health-care law is unconstitutional; only 38 percent believe it constitutional, and 6 percent gave no answer.

Let me assume for the moment that the Supreme Court finds the health-care legislation unconstitutional. From the survey evidence, this would be a decision pleasing to a majority of Americans, and mustering an anti-court majority in response to its decision would be difficult.

On the other hand, assume that the court finds the legislation is constitutional; only 38 percent of the American people would be pleased by this outcome, a decided minority.

Here’s where legitimacy comes into play. Assume that about a half of the American people extend reasonably strong legitimacy to the Supreme Court (the actual figure is likely considerably higher, but, for the sake of argument, I am using a conservative estimate). Applying this percentage to the losers under a Supreme Court decision of constitutionality — the 56 percent — gives us 28 percent of the total.

If we combine the 38 percent happy with the outcome with the 28 percent willing to stand by the court even when it makes a disagreeable decision, then a majority of the American people — 66 percent — would reject proposals attacking the court.

This arithmetic of legitimacy explains how the Supreme Court can successfully go against the substantive preferences of the majority. Because at least one-half of the losers acquiesce to decisions to which they object, it is difficult to build a majority coalition to attack the Supreme Court as an institution for any given decision it might render.

On most issues before the Supreme Court, the sum of those pleased by the court’s decision and one-half of those displeased will exceed 50 percent of the population.

And so it will be with the health-care litigation.

Undoubtedly, fierce criticism will be leveled against the decision by the losers. But, as with Bush v. Gore, efforts to transform this criticism into a successful attack on the court as an institution will be highly unlikely to succeed.

The Supreme Court may make the “wrong” decisions on health care and other issues this spring. But as a widely legitimate institution, the court will be able to make these decisions with impunity.

As it stands today, the U.S. Supreme Court is in fact nearly invincible. For better or for worse.

The data in this article are draw from an annual national survey Gibson conducts – the Freedom and Tolerance Survey – supported by the Weidenbaum Center at Washington University in St. Louis. For a more technical and expansive version of the argument presented in this article, see Gibson, James L. 2012. “Public Reverence for the United States Supreme Court: Is the Court Invincible?” Paper delivered at the Countermajoritarian Conference, University of Texas Law School, March 29–30, 2012.