THE PROBLEM: California is considered ungovernable because the complicated system leaves no one in charge. Instead, elected officials manage a constant crisis, and no one does long-term planning. “California’s struggle is an issue of governance. Governors in California don’t have much power, at least the way it is today,” says Nicolas Berggruen. Think Long sought to answer questions: Who could run the state? Who could make long-term decisions?

THE BACKSTORY: Berggruen personally engaged most closely on this subject, committee members say, and the final report reflected his thinking. When he spoke in meetings, Berggruen often mentioned countries that had empowered certain leaders— or particular committees—with the power to make decisions, and protected them from short-term political considerations.

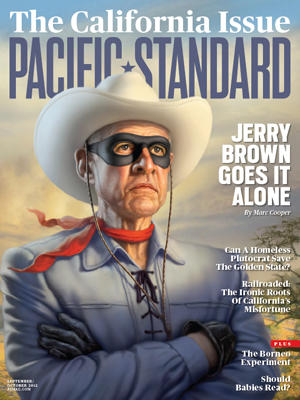

California Issue

What is Think Long thinking?

The Think Long Committee developed specific recommendations for improving California’s governance. Joe Mathews offers an in-depth look at seven specific areas afflicting the state, and what the reform organization proposed as remedies. The other six areas are:

Taxes

Voter Initiatives

State Budget Deficit

Jobs

Education

Local Government

The committee started this discussion by considering how they might make the Legislature a more powerful force for governance. Bob Hertzberg, a former speaker of the state Assembly, urged consolidating the two houses of the state Legislature into one house; this unicameral body would be designed to be more representative and have a strong committee system. Instead of a second house, the committee examined remaking the state’s tiny Office of Planning and Research, now the research arm of the governor’s office, as a “Citizen’s Cabinet” made up of 15 to 18 eminent Californians who would be appointed, not elected, and serve set terms.

The committee ultimately decided that crafting a unicameral legislature was too complicated since it required so many additional changes to the constitution. But the “citizen’s cabinet” idea grew and morphed over discussions.

It would eventually be called a “citizens’ council.” The committee wanted some kind of super-body that had broad powers and was protected from short-term politics. But what should those powers be and what should the group look like?

California, as a legacy of its progressive era, has hundreds of boards and commissions that are held separate from politics. Think Long studied them the big ones: the transportation commission, the boards of pension funds, and the Little Hoover Commission, a California body that studies, and can approve, some governmental reorganizations.

THE PROPOSAL: Former governor Gray Davis said that this council should have power to manage and make decisions over long-term investments and capital outlays; the Council on Virginia’s Future, in that state, was discussed as a model. Think Long members also believed that the membership should look something like the University of California regents, whose members are appointed by the governor to 12-year terms, as a way of promoting long-term thinking. (The proposed council started with 21 members. It shrank during the Think Long deliberations to 13 members, nine of them appointed by the governor, on the theory that he had the broadest statewide constituency of any California official.). There would be a host of protections for the council, including a guaranteed budget that couldn’t be cut by the Legislature or governor.

But that wasn’t enough. The council, Think Long members agreed, needed more than protection. It needed teeth. So the committee resolved to give the council the authority to subpoena documents from other parts of the legislature.

“If pointing out malfeasance, incompetence, ineffectiveness and waste does not result in change, The Council should be empowered to draft initiatives,” notes of the meeting said. This would be a considerable power (for other California citizens, qualifying a measure for the ballot requires legal reviews and a $3 million-plus signature-gathering campaign)—and offer another window for initiatives to be on the ballot.

Such a council, if enacted, would be the new beating heart of state government. In a state where reformers were framed as fundamentally democratic (even if they weren’t), this council would be unapologetically elitist—albeit in the service of creating a democratic space with officials who could plan for the long term and make real decisions.

This was a major departure, and Think Long knew it. Documents from the meeting at which it was approved read: “TLC proposes below what we believe is the most significant governance reform in recent California history.”