We’re just over four months away from the 2014 congressional mid-terms, and news reports are starting to turn to the general elections in speculation of what might tip things toward one party or the other. I thought now might be a good time to talk about what we know generally does, and doesn’t, affect the mid-terms.

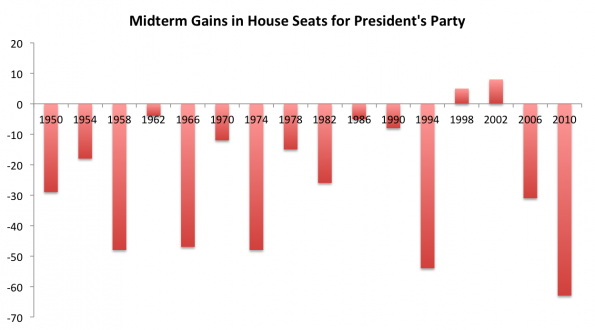

Just for starters, here’s a graph showing how the president’s party has performed in U.S. House mid-term elections going back to 1950. As is clear, it’s pretty common for the president’s party to lose seats; this happened in every election except 1998 and 2002. Both of those election cycles featured unusually popular incumbents. (Clinton oddly benefited from the impeachment coverage, and Bush was experiencing high approval ratings in the wake of 9/11.)

While losses are the norm, they’re clearly not consistent, ranging from Democrats’ modest four-seat loss under Kennedy in 1962 to their record 63-seat loss in 2010 under Obama. What explains this variation?

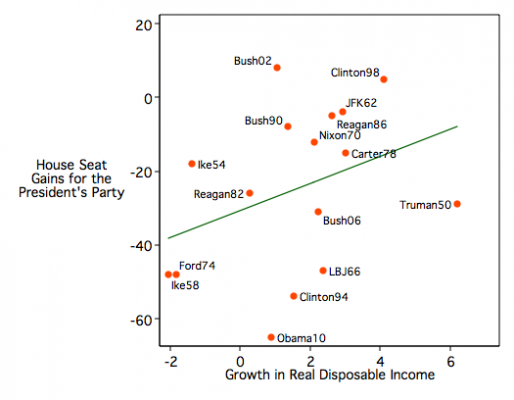

One big influence is the economy. National economic growth (although not overall unemployment levels) seems to determine how the president’s party will do. As the graph below shows, when the economy is stronger, the president’s party does better, or at least less horribly. The biggest wipeouts for the president’s party occur when the economy is weaker. Democrats gained seats under Clinton in 1998 in large part because the economy was booming.

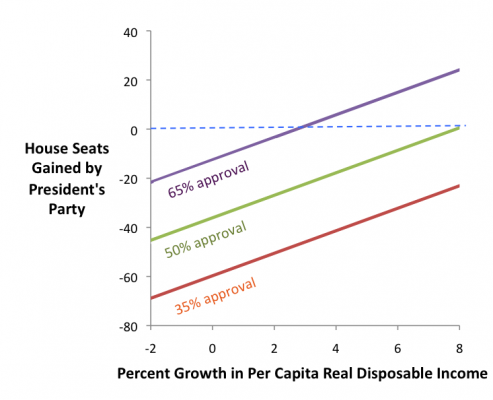

The popularity of the president also seems to be important. Even though Obama’s name will appear on no ballots this fall, he’s there at the back of voters’ minds. They’re thinking about him when they decide how the Democrat in their district is doing. Obama’s approval rating is hovering around 45 percent right now and pretty likely to stay there through the fall—he has one of the most stable approval ratings of any president in history. The chart below shows the interaction of presidential approval and economic growth on the performance of the president’s party in House elections. As can be seen, Obama could save his party quite a few seats by somehow adding 20 points to his approval rating, but again, that’s pretty unlikely to happen.

Another key variable is the exposure of the president’s party. That is, when they control a lot of seats, they’re more vulnerable. In 2010, Democrats held 257 House seats. These included many moderate to conservative districts that Democrats normally don’t control but had managed to win thanks to favorable electoral environments in 2006 and 2008. That left the Democrats very exposed when the wind turned against them. This year, they only control 201 seats in the House, and those districts tend to be pretty reliably liberal. So they’re not likely to lose many seats. (It’s the Senate’s six-year terms, though, that make Democrats particularly vulnerable in that chamber. The Democrats up for re-election this year won in 2008, a very Democratic year. They now have to defend moderate to conservative turf in a pro-Republican environment.)

To some extent, the voting behavior of incumbent members of Congress matters. Members who seem to vote with their party too often can sometimes appear to be out of step with their district, and voters may punish them for that. Sometimes, this comes down to a single roll call vote. Democrats who voted for the Affordable Care Act in 2010 actually did about six points worse at the polls than Democrats who opposed it. This is a large part of the reason that Democrats performed so historically badly in that election cycle. There probably isn’t a single toxic vote like that in this year’s cycle, and support for/opposition to Obamacare is already baked into people’s evaluations of the parties.

Finally, primaries can matter, as they affect the quality of the candidates that appear in the general election. The Cantor-Brat primary in Virginia was a big deal in part because it replaced a seasoned pol with a novice as the Republican nominee. It’s a safe Republican district, so that probably won’t affect the November outcome a great deal, but this can make a big difference in more competitive districts. The Republicans may have lost out on several relatively easy Senate pickups in 2010 because Tea Party insurgents defeated more electable candidates in the primaries.

That’s most of what we find matters in mid-term elections. Now, a Google search lists many other possible influences on this year’s election, such as Bowe Bergdahl’s release from the Taliban, Obamacare enrollment figures, foreign policy crises in such places as Ukraine and Iraq, campaign fundraising, unemployment figures, and so forth. Will these things affect the elections? Probably not, or at least not directly, and not in the aggregate. (They could affect Obama’s approval ratings, for example, which could then influence the elections, but it’s pretty tenuous.) It’s not that these other stories aren’t important, it’s just that they won’t actually drive many people’s votes.