As an American living in Canada, I can’t count the times I’ve been told that I’m “ahead of the curve” since the night of November 8th, when the government’s immigration website crashed as a result of all the Americans who suddenly found the grass looking much greener north of the border. Justin Trudeau’s peachy image of Canadian values — the celebration of diversity chief among them — have often been held up as the antithesis of President Donald Trump’s dark “America first” vision by Western liberals. But following the massacre of six Muslim men at a Québec City mosque in January by a young white nationalist, many Americans and Canadians alike began to wonder aloud for the first time whether Canada was as much of a safe haven as it seemed.

On that frigid night in Sainte Foy, a large suburban neighborhood west of Québec City, Alexandre Bissonnette put to rest any illusions that Canada might be immune to the far-right populist movement sweeping the globe. The past few weeks have seen swastikas etched on the wall of a college classroom in Toronto, and bomb threats placed by a group calling itself the Council of Conservative Citizens of Canada targeting Muslims.

This recent chain of events follows a longer-running narrative. Between 2013 and 2016, anti-Muslim hate crimes rose 525 percent, according to the National Council of Canadian Muslims. The Federal Bureau of Investigation reported 257 “anti-Muslim incidences” in the United States in 2015 — about 4.5 times as many as in Canada that year — but that’s in a country with almost 10 times the population.

A February poll found that only 15 percent of Canadians approve of Trump, while Trudeau enjoys a 52 percent approval rating. There is no reason to assume that such a riotous change of direction will take hold in Canadian politics, but there is no doubt that the same forces are at play above the 49th parallel. Meanwhile, the American left-wing media has continued to hail Canada as one of the last liberal democracies standing.

Signs of a Trumpist movement in Canada have been brewing for quite some time, though its architects have only now come out of the woodwork. The week after Trump’s election parts of Toronto were papered with alt-right flyers that asked: “Hey white person, tired of political correctness?” Racist harassment and online hate-mongering spiked after November 8th — to the shock of most mainstream Canadian political pundits — and hasn’t let up.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Late last year, Kellie Leitch, a parliamentarian from Ontario who is running for the leadership of the national conservative party, called Trump’s victory an “exciting message” for Canada. While she was condemned in the media, her alignment with Trump helped bump her to the front of the leadership race, positioning her as the future prime minister should the conservative party regain power in Canada (In May, the conservative party will elect a new leader in the Canadian equivalent of a presidential primary; the next election for prime minister is not until 2019). Central to Leitch’s campaign is a call to screen prospective immigrants for “anti-Canadian values,” which some political commentators have equated with Trump’s Muslim ban. Polls show that about two-thirds of Canadians support the idea.

A few weeks later, Canadian liberals’ collective jaw dropped another inch or two following news of a very Trump-like political rally in Edmonton in which a crowd assembled in support of Chris Alexander, the right-wing immigration minister from the Stephen Harper regime who is running against Leitch for leadership of the national conservative party. At one point, the mass of bodies erupted in a spontaneous chant of “lock her up” — not in reference to Hillary Clinton, but to Rachel Notley, the liberal premier of Alberta.

A few weeks ago I attended a town hall-style meeting on the rise of racism and intolerance in Canada held at a church in my neighborhood in Toronto. The meeting started out peaceably enough. Moderated by our local representative in Parliament, Arif Virani, a Muslim human rights lawyer who came to Canada as a Ugandan refugee in 1972, the panel onstage included activists from the black Canadian, women’s rights, transgender, aboriginal, and Islamic communities. The conversation centered on how to keep the tide of hate from sweeping northward.

“We have to push back those forces!” said a tall, distinguished-looking gentleman in a long robe and crocheted prayer cap as he grasped his long white beard. “Trump is bringing the racists in Canada off the sidelines!” The crowd roared. Sentiment in the room was decidedly anti-Trump, here in this trendy, progressive part of town — but not exclusively.

After a while a woman stood to speak, identifying herself as an ex-Muslim from Saudi Arabia. She was very concerned about Canadian imams who held a traditionalist interpretation of the Koran that subjugated women. They wanted sharia law in Canada, she said. Some even condoned jihad, she added, holding up a stack of papers as evidence, her voice rising. Those in the room who had been nodding in agreement began to stiffen. “We have to put an end to Islam!” she shouted.

Now her companion, a balding white man with glasses, stood at her side. “Islam equals death!” he screamed, jeering toward the panel. “This church should be ashamed to invite these dirty Muslims!”

Virani thanked the two for their input and firmly suggested they leave the meeting. The man held out his phone toward the crowd, weapon-like, as if he was a protester about to film a confrontation with riot police. Virani’s staff began to escort them from the building.

“I am Charlie Hebdo, I am…,” the man trailed off as he exited, listing the victims of recent terrorist attacks. The room finally exhaled.

I later learned that the same folks have pulled similar stunts at public meetings across the Toronto area. They are the local frontmen for Rise Canada, a national group that advocates for anti-Muslim policies, such as the Québec Charter of Values — proposed (and subsequently defeated) legislation that would have banned people from wearing burkas, burkinis, hijabs, niqabs, and turbans in public institutions. Though shot down in 2013, the Charter of Values continues to be floated by the Parti Québecois.

“Canada tends to be more centrist, politically and culturally, but that’s not to say that we don’t have our own biases, both latent and evident.”

Along with groups such as Never Again Canada, Canadians Against Islamization, and Suffragettes Against Shariah, Rise Canada has launched campaigns around the country against M-103, recently proposed federal legislation intended to crack down on anti-Muslim discrimination. A few days after the town hall meeting, adherents of Rise Canada made headlines when they hoisted signs equating Muslims with terrorists outside of a mosque in Toronto. Toronto police investigated the incident as a hate crime, but no charges have been made. By the end of the day a spontaneous counter protest, involving about twice as many people, erupted as the nationalists dispersed.

Central to Trudeau’s 2015 campaign for prime minister was a promise to fast-track 30,000 Syrians through the immigration portals during his first year in office. This, and his earnest pledge to champion indigenous rights, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, and every other humanitarian cause you can think of, swept him into office in a crushing defeat of Stephen Harper, the deeply conservative incumbent.

“Sunny ways, my friends, sunny ways,” Trudeau said upon his victory, ending his acceptance speech with a foot-stomping affirmation of the country’s long-held identity as a bastion of tolerance and inclusivity: “A Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian!” This was Canada’s Barack Obama moment; hope, justice, and hipness were in the seats of power like never before. Canadians felt like they had their country back. At least the liberals did.

Trudeau — the handsome, boyish son of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau — set out to spread his loving message across the land. He greeted refugee children at the airport with an armful of winter coats one month, and cuddled with baby pandas at a zoo the next. Last summer he made quite a splash at the Toronto gay pride parade in his pink linen shirt, white pants, and beads.

Trudeau outdid his promise to admit Syrian refugees by 30 percent (approximately 60,000 refugees were admitted last year, roughly two-thirds of them from Syria). He also made sure there was perfect gender parity in his cabinet — 15 male ministers and 15 female ministers — including a turbaned Sikh, a Kwakwaka’wakw woman from British Columbia, an Inuit man from Nunavut, and the first ever Muslim minister. He gave each one a bear hug after they were sworn in.

On face value alone, the Canadian cabinet is far different from its Washington, D.C., counterpart — which helps to explain not only the anti-Muslim backlash, but a wider phenomenon of right-wing demagoguery. The rising tide of liberals in power has energized the illiberal fringe.

“Canada tends to be more centrist, politically and culturally, but that’s not to say that we don’t have our own biases, both latent and evident,” says Barbara Perry, a professor at the University of Ontario and one of the foremost experts on hate crimes in Canada. “We are not completely immune to what’s happening to the south of us. Some of the same fissures are occurring here.”

Perry says xenophobic sentiment has always lurked in the shadows here, but Canada’s much-celebrated multi-cultural identity — a hard won identity that has its historic roots in the efforts to reconcile animosity between Anglo-Canadians and the Francophone minority — has long hog-tied the bigots, culturally speaking. Just as in the U.S., 9/11 loosened the knots a bit — and now far-right nationalists have come along with the scissors.

Of course, electing a demagogue requires a demagogue to run in the first place. Even though Leitch has alt-right leanings, she has not shown a lack of respect for the basic norms and institutions of democracy, nor does she appear to be especially prone to dishonesty.

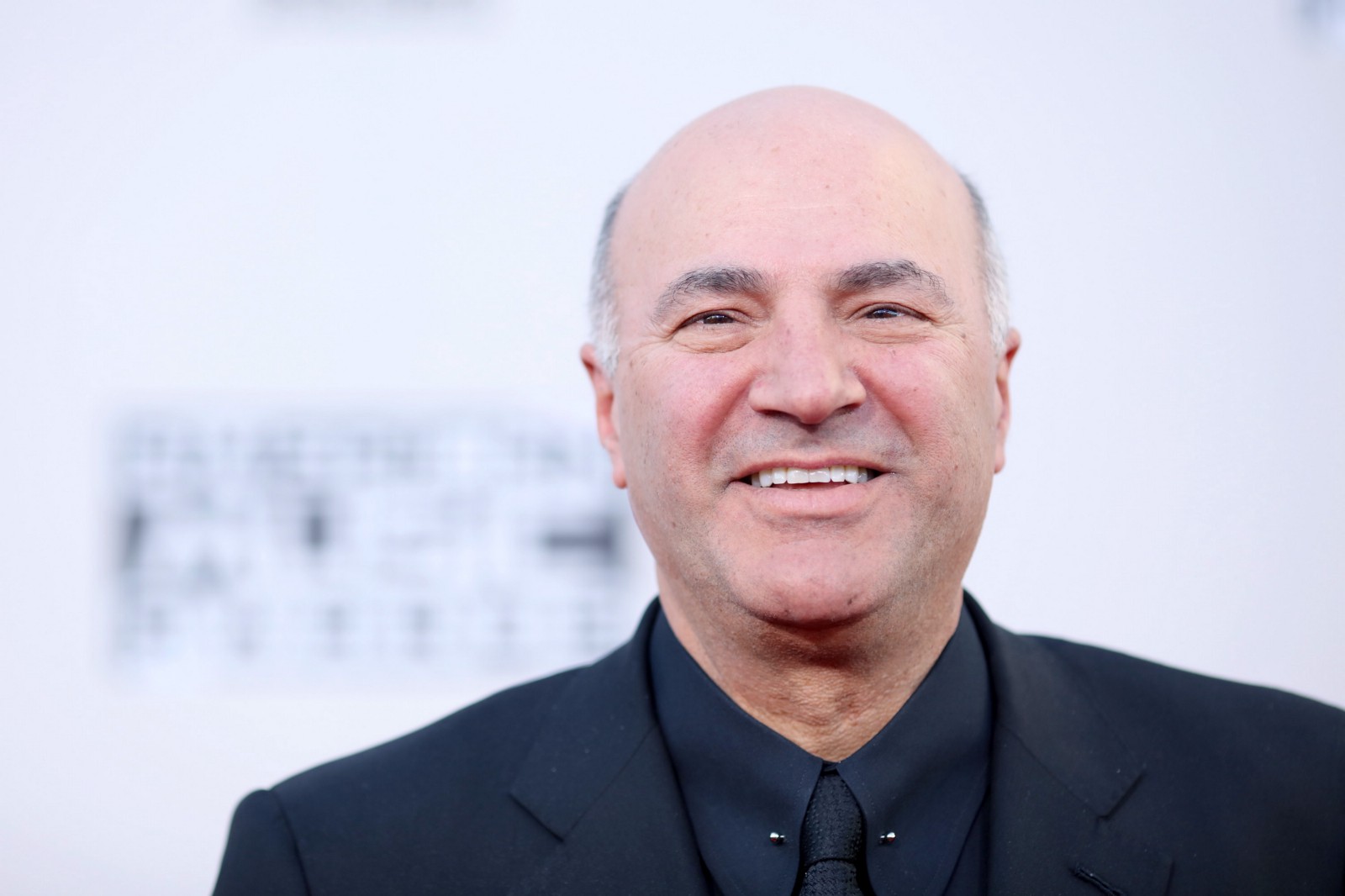

Another frontrunner in the conservative race, Kevin O’Leary, who announced his candidacy in January, is a bit more like Trump’s Canadian twin, at least in personality and occupation: a shock-jock business mogul who dabbles in reality television (he’s the host of Shark Tank in America, along with other similar shows broadcast in Canada), with no political experience. He refers to himself as “Mr. Wonderful.” Like Trump, for whom O’Leary has professed his admiration (“hail King Trump,” he proclaimed in a January interview), he shows a knack for parlaying his atonal approach into news cycle dominance. Just as mourners gathered at a memorial service in Quebec City for the victims of the mosque shooting, O’Leary made headlines for posting a Facebook video of his day at a Miami gun range in which he is seen firing a heavy-calibre sniper rifle.

(Photo: Mark Davis/Getty Images)

Like Trump, the mainstream Canadian media has heavily criticized both O’Leary and Leitch. But in Leitch’s case, she’s found an ally in the unconventional, controversial Rebel Media — essentially a Canadian Breitbart. (Rebel Media is harder on O’Leary, whom it considers an imposter of sorts.) A recent start-up, the news site is fronted by a motley crew of alt-right revolutionaries, including 21-year-old Lauren Southern, who gained global recognition last year for a social-media stunt she dubbed “The Triggering.” Planned for the day after International Women’s Day, the goal was to blanket the Twitterverse with offensive content, just to irk liberals (and, as she claims, to make a point about free speech). Currently a political science major at the University of the Fraser Valley in British Columbia, Southern is registered as a parliamentary candidate in the Libertarian Party of Canada. For anyone who is unclear on exactly what her ideology is, Southern just self-published a book, titled Barbarians: How Baby Boomers, Immigrants, and Islam Screwed My Generation. As of the time of this writing, it is the No. 1 seller on Canada’s Amazon website.

Does the Canadian alt-right have any real chance of seizing political power? Political scientist Stefan Dolgert believes it’s not an implausible scenario.

Dolgert is a professor at Brock University in St. Catherines, Ontario, which lies smack in the middle of Canada’s Rust Belt. Few Americans know Canada has a Rust Belt, and, until recently, most Canadians weren’t aware of the fact either. The “rust” that consumed Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh in the 1980s and ’90s didn’t creep across the border into southwest Ontario’s manufacturing sector until about 15 years ago. According to a report by TheEconomist, roughly 20,000 Canadian factories shut their doors between 2002 and 2012.

Dolgert says the Canadian Trumpists, at least in Ontario, have been busy grousing about the electric bill (known in Canada as the hydro bill), which has risen four times faster than the rate of inflation over the last decade, in part because coal-fired power plants were phased out completely during this period. Kathleen Wynne, Ontario’s left-leaning lesbian premier has seen abysmal approval ratings of late as her opponents have successfully turned the power bill into a wedge issue.

“The hydro bill increase is getting rolled into a larger story about how out of touch the provincial government is,” Dolgert says, adding that the same thing is occurring nationally as liberals have sought to impose a carbon tax, which conservatives see as a fatal blow to Canada’s struggling oil sector. “There is a populist bent to this. Canadian conservatives watch what American conservatives do and they try to emulate it. I think the fact that Canadians rely on the government to do a lot more for them than in the U.S. actually makes us more vulnerable to that line of ‘look at how much power we’ve vested in these bureaucrats who don’t care about us, and now they’re wasting money left and right.’”

Canada’s parliamentary system of government — in which the legislative and executive branches are intertwined, unlike the distinct divisions of the federalist system in the U.S. — is often credited with preventing extreme partisanship, but it also means the prime minister has more unilateral power, and is always of the same party as the majority in the House of Commons. Dolgert points out that Canada’s electoral system, in which the electorate has not two but five major parties to choose from, means the ruling party is usually elected with less than 40 percent of the popular vote

These facts stoke fear among those Canadians concerned that an authoritarian-style leader could be pushed to power by a minority of the population. Dolgert shares that fear, but says it is tempered somewhat by another facet of Canada’s parliamentary system — known as the vote of no confidence — which enables the overthrow of an inept, corrupt, or unpopular leader on a moment’s notice, and the quick election of a new prime minister. While the party of the prime minister always holds a majority of seats in parliament, it sometimes lacks an absolute majority (more than 50 percent); in this case the other parties may band together in a vote of no confidence.

A successful vote of no confidence has occurred numerous times in Canadian history, most recently with Harper. It’s a way to stop a demagogue in their tracks, without needing to prove criminal wrongdoing, as in the case of American-style impeachment.

Despite their concerns, neither Perry nor Dolgert believe a full-blown Trumpian crisis is in the cards for Canada in the near future. “I think there are glimmers that we have learned something from Trump’s rise,” Perry says. “We’re already seeing the fallout in the U.S., so I hope Canadians can resist.”

Dolgert points to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the centerpiece of Canada’s 1982 Constitution, as an imposing bulwark for any aspiring authoritarians in the country. “Multiculturalism is written into the Constitution in a way that it is not in the US,” he says. “It has a more sound legal structure here.”

As political commentator David Alexander has written, the Canadian Constitution is a “younger, hipper” version of America’s, with “a fundamentally different way of thinking about rights … [including] some sexy new ideas that weren’t around in the 1700s.” Pierre Trudeau, who spearheaded the adoption of the 1982 constitution, certainly wasn’t envisioning a Bill of Rights that didn’t apply to slaves he owned, as was the case with the framers of the U.S. Constitution.

“Canadian conservatives watch what American conservatives do and they try to emulate it.”

Canada’s liberalism may have a more sound historical footing than in the U.S., but, despite Trudeau’s continued popularity, public support for the Liberal Party has fallen in the polls to a dead heat with the Conservative Party, and it is increasingly clear that the conservatives will attempt a Trump-style campaign in the 2019 federal election. In February, four of the candidates vying for party leadership showed up at a Rebel Media-sponsored rally in Toronto, including Leitch, who took the Liberals to task over M-103, their anti-Islamophobia bill, proclaiming, “we need to fight back against all of this politically correct nonsense.”

Meanwhile, O’Leary, who has pulled ahead of Leitch in the polls for the upcoming conservative leadership election in May, found himself in an awkward moment on CNBC’s Halftime Report, defending Trump’s rocky first month in office in a live conversation with Mark Cuban, the American billionaire who co-stars with O’Leary on Shark Tank. Cuban pressed O’Leary about his adoration for Trump, his motivations to run for prime minister, and the reasons he preferred the Canadian parliamentary system over the separation of powers found in the American system.

“Tell them what you told me,” urged Cuban, referring to a previous conversation he’d had in private with O’Leary. “Explain to viewers and listeners what you love about the parliamentary system in Canada.”

O’Leary attempted to dodge the question, but finally spilled the beans. “It’s a fact,” O’Leary said, “[that] the parliamentary system provides more power to the prime minister.”

Cuban shot back: “What you like about it is that you get carte blanche [power].”

“No, Mark,” O’Leary retorted, bringing up the vote of no confidence as Canada’s safeguard against authoritarian impulses. “That’s an unfair characterization of the Canadian system.”

O’Leary is right about that, but the exchange provided a clear characterization of his attitude about leadership. Like Trump, O’Leary says voters are flocking to him because he’s “not afraid to tell them how it is.” Perhaps Canadians will take his words at face value, and vote against the neo-authoritarian tide.

Lead Photo: Canadian flag. (Photo: Harry Sandhu/Unsplash)