Drive across the United States and stop in a dozen different diners off the interstate highway. In between bites of your bacon cheeseburger and a second order of ice tea, lean over and talk to the guy at the next booth. Ask him what he thinks about the role of government and his political rights. Those 12 guys in those 12 diners in those 12 different corners of our country will probably tell you something similar. In this country, there is a broad consensus around certain notions of politics and society.

Almost all Americans believe that individuals have certain natural rights, including the right to self-defense and the right to own property. We believe that the purpose of government is to serve the citizens, and we believe that citizens have a right to replace a government when it ceases to protect those citizens. Thomas Jefferson borrowed those concepts from English and Scottish Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke and John Hume and then neatly summarized them in the Declaration of Independence. Now, they are engrained in the American imagination.

Is it possible to find political consensus around public policy in a nation so divided? When we are composed of so many different political cultures, will we ever come to an agreement around issues like gun control, gay marriage, and education?

At the same time, you’ll see a lot of variation in the details of American political life during that drive. You can buy pot for recreational use in Colorado—but make sure to smoke it all before you enter Utah. If you are gay and married in New Jersey, that marriage will all but disappear as you cross the border into Pennsylvania, and then suddenly re-appear as you drive into California. In Texas, carrying a concealed weapon is easier than ever before, but you should lock up your weapon at home while visiting New York City. Apparently, Americans interpret those broad Jeffersonian concepts of government, rights, and freedom in different ways, largely depending on where they live.

Political scientists describe a phenomenon known as state political culture, which is a set of beliefs and attitudes that are consistent over time and confined to a certain geographic area. Some experts say that we owe these variations in political beliefs to the original immigrants who settled in different parts of the country.

These immigrants brought their grudges and Old World values to the United States, and those views melded with new American values. The Puritans stamped their views of society and politics on the Northeast, and the Scandinavians put their own mark on the Midwest. Northern New Jersey, which I call home, was shaped by the original Dutch settlers, as well as by the latecomers of Irish and Italians to the port-side cities.

In 1972, the celebrated political scientist Daniel Elazar wrote that each state has its own political culture shaped by the original settlers in the state. He divided the country into three different political cultures: moralistic, individualistic, and traditional.

Puritans—and, later, Scandinavians—settled in the North and migrated across the country. They were motivated by the belief that they could establish “a city on the hill,” that politics was a means for improving the community. States with a moralistic political culture (blue on the map) have high levels of political turnout, more progressive politics, and less control from party elites.

The Irish and Jews, who came to U.S. looking for improved conditions for themselves and their families, settled the individualistic states (yellow). Politics was seen as a route to improve one’s position. States with this culture tend to have higher levels of corruption, more control by party elites, and lower levels of turnout.

Elazar said that the traditional states (orange) were shaped more by the plantation lifestyle—as opposed to a particular immigrant group. Their culture is based on preserving hierarchy and status quo. They also have high levels of party control.

In Albion’s Seed, David Hackett Fisher argues that there are four major “folkways” in America, which have grown out the cultures of four different regions in England. The Puritans came from East Anglia and settled in the Northeast. Southern Englishmen settled in the South and became planation owners in Virginia. Immigrants from the North Midlands area of England later became the Quakers in the Middle Atlantic and Midwestern United States. The Scotch-Irish on the border of England influence Western ranch culture and Appalachia.

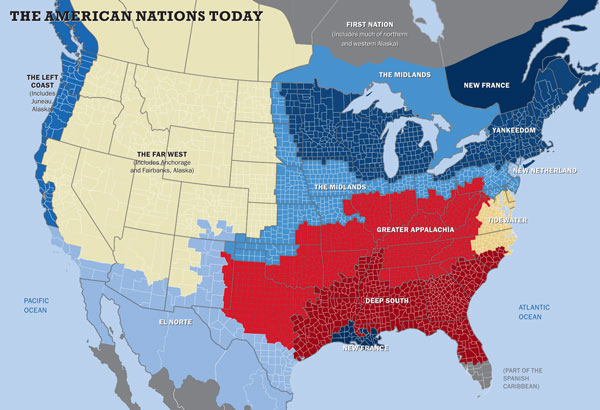

In a similar vein, journalist and author Colin Woodard writes that America, influenced by original immigration patterns, is made up of 11 different nations. His 2012 book, American Nations, outlines each of these 11 regions and their unique perspective on government.

Like Elazar, Woodard says that the Puritans and the Scandinavians helped shape the Northeast and Upper Midwest, a region he calls “Yankeedom.” This “nation,” he argues, is more comfortable with government regulation, values education, and the common good than other regions.

The coastal areas of Delaware, Virginia, and North Carolina Woodard calls “Tidewater.” The younger sons of southern English gentry settled in this area, where they reproduced the feudal ways of the old country. Therefore, “Tidewater places a high value on respect for authority and tradition, and very little on equality or public participation in politics,” Woodard writes. (He provided further description of his “nations” in an essay for the fall 2013 issue of Tufts magazine.)

Is it possible to find political consensus around public policy in a nation so divided? When we are composed of so many different political cultures, will we ever come to an agreement around issues like gun control, gay marriage, and education?

Maybe. Maybe not.

Perhaps we should accept that we are a country that agrees about certain basic things, but clashes over the specifics. We’re a very large and very dysfunctional family at the Thanksgiving dinner table that quarrels about the side dishes, but all expect—and overlook—the turkey main course. Dysfunctional families, after all, work, and their flexibility might ward off bigger crises and conflict. There’s a place for everyone.

It is unlikely that we’ll see the erosion of these different state cultures in the near future. The legacy of the diverse immigrants who shaped this nation will continue to influence our political decisions for years to come. Our decentralized structure of government enables this diversity to continue and, thus, we end up with 50 different systems of schools, 50 different laws on guns, and 50 different rules about abortion.

So, whether you’re chatting with a stranger at a small-town hangout or going home to a meal with your family, you are bound to get an earful once you get past the basics and move to the specifics. It seems that we Americans are born to fight.