The rise of the oceans has Pacific island nations in a state of crisis. Tropical cyclones have become more frequent and more deadly: On average, at least 10 of them will hit these nations between November and April every year. Many of the islands sit just above sea level. With others, the elevation is measured in millimeters. In a bid to strengthen food security, Kiribati has spent millions of dollars buying land in Fiji from the Church of England, while citizens from the country’s outer islands have begun a steady migration to the somewhat more stable capital island of Tarawa.

These islands can’t lift themselves out of the water, though they’re doing their best. As the ice sheets continue their decline, projections for South Pacific populations become more dire by the minute, and we’ve already seen increasing rates of saltwater intrusion, drought, and storm surges. Internal migration is not a durable solution for the people of these nations, and international law does not afford refugee status to climate migrants. This September, New Zealand deported Ioane Teitiota, a Kiribati man who’d come to the country seeking climate asylum; the Supreme Court of New Zealand had assessed the relevant body of international law and found no basis for recognizing Teitiota as a refugee. From the Court’s decision in July:

In relation to the refugee convention, while Kiribati undoubtedly faces challenges, Mr. Teitiota does not, if returned, face “serious harm” and there is no evidence that the government of Kiribati is failing to take steps to protect its citizens from the effects of environmental degradation to the extent that it can.

These problems are of a piece: The islanders have little to no voice in international energy policy, and exert, at most, limited influence over international law. Yet the truth remains that climate change—much like ethnic cleansing—does indeed single out certain populations, presenting migration problems every bit as serious as those of political, religious, and ethnic refugees. Extinction is hardly less serious than genocide, yet its quarry have no legal basis to relocate.

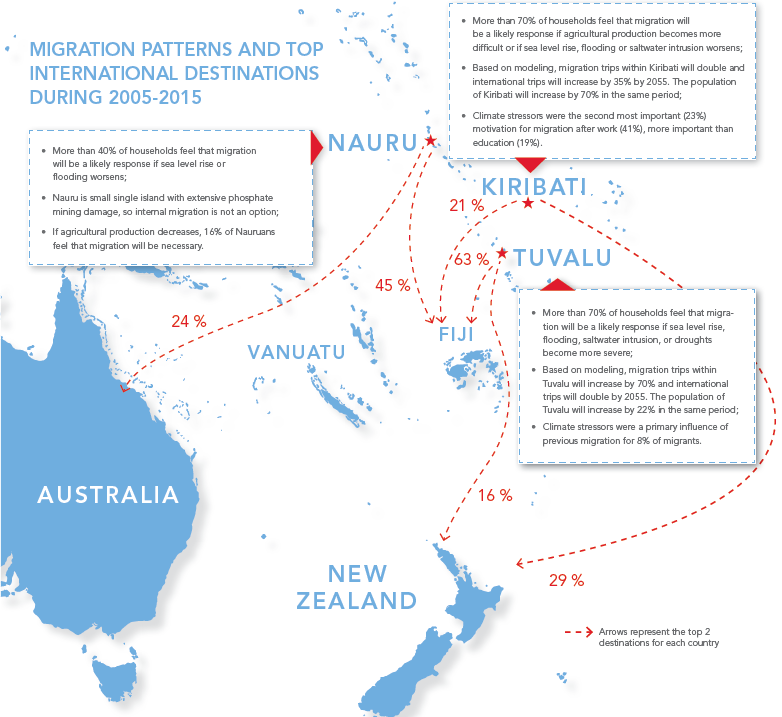

At COP21 this morning, these inequities were at the fore, as the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), in partnership with the U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), presented a sweeping survey among the populations of Kiribati, Nauru, and Tuvalu, alongside much-needed policy recommendations for the international community.

The survey—launched by UNESCAP but executed largely by locals—canvassed 852 households (6,852 people) in these three countries. It’s the first comprehensive look at the migration patterns and climate anxieties of these islanders. As Tuvalu’s Prime Minister Enele Sosene Sopoaga put it in a prepared statement: “The results from this unprecedented survey show us empirically what we already know. Pacific islanders are facing the brunt of climate change impacts and are increasingly finding themselves with fewer options.”

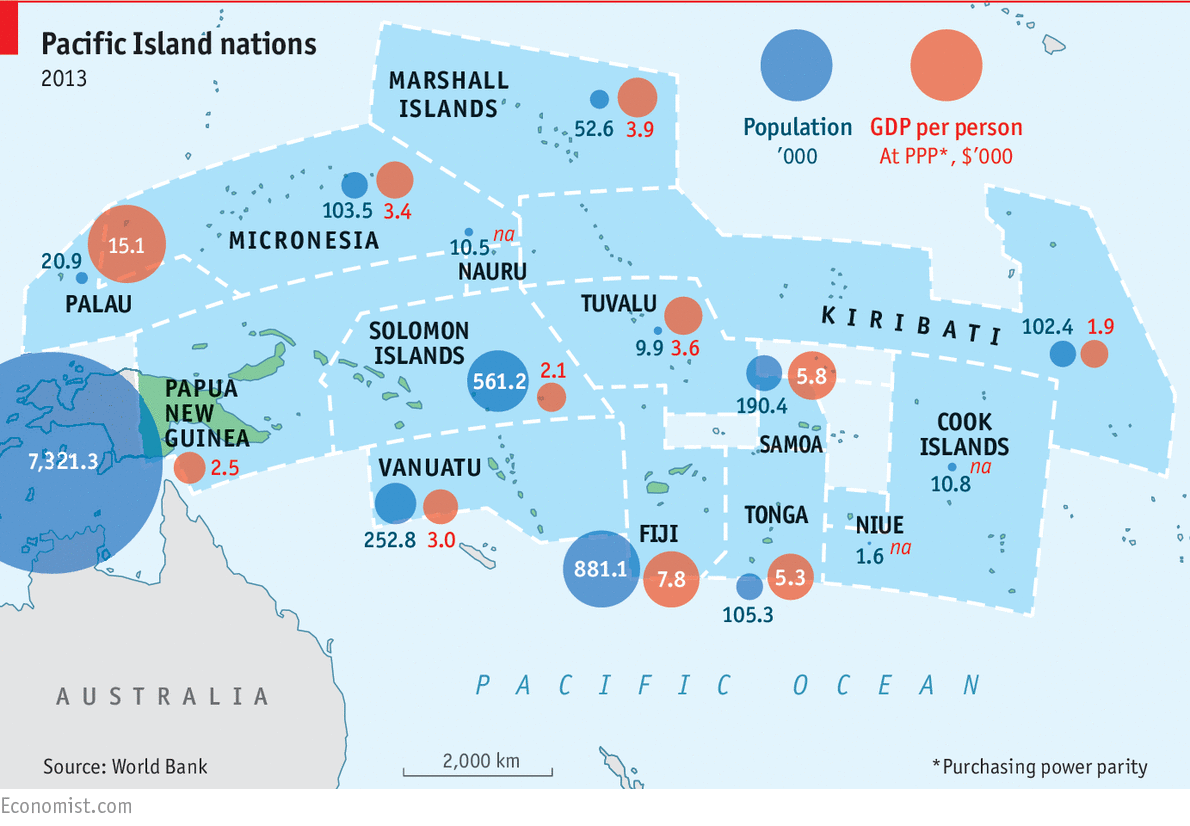

More than 70 percent of households in Kiribati and Tuvalu (and 35 percent of households in Nauru) said family members would wish to migrate if “climate stressors” continue or worsen. Meanwhile, only around a quarter of those households could actually afford to move—let alone find welcoming homes elsewhere on the globe. Sopoaga exhorts us to make possible “migration with dignity,” a noble and deeply ambitious goal. Ten percent of Nauru’s citizens and 15 percent of Tuvalu’s emigrated between 2005 and 2015; predictive models among UNESCAP researchers suggest that, by 2055, international emigration from Kiribati would increase by 35 percent; from Tuvalu, by 100 percent.

What can the rest of us do? Some straightforward stuff with job training, risk-management tools (simple facilities for storing water, for example), and, perhaps most crucially, international law. To ease migration, the U.N. also advocates training island citizens as nurses, schoolteachers, and police: Such training would help strengthen visa applications for emigration to better-elevated countries, and help émigrés find good work once they get there.

“In climate change migration research, the lesson is how unprepared we are, and how unequipped our legal and institutional arrangements are,” Dr. Koko Warner, senior expert at UNU-EHS, said this morning. “We have arrangements for economic and political migrants but not climate migrants.”

“Something we’ve learned from the president of Kiribati is the importance of joint visa arrangements, and possibly joint passports, that allow people to move in a safe, regular way,” Warner continued. “The flows of people today are complex, and our mobility institutions were really designed for a previous century.”

It’s high time that international community develop new, legal means for climate mobility, and not just for island nations. Climate change is driving a new breed of refugee crisis: one without a single point of origin, and with no prospect of return.

“Catastrophic Consequences of Climate Change” is Pacific Standard‘s year-long investigation into the devastating effects of climate change—and how scholars, legislators, and citizen-activists can help stave off its most dire consequences.