As medical science improves, the line between “sick” and “different” becomes harder and harder to draw.

By Malcolm Harris

(Photo: Bjorn Knetsch/Wikimedia Commons)

The central promise of contemporary advances in medical technology is that, in the near future, doctors will be able to cure debilitating conditions that we once imagined were permanent. The paralyzed will walk, genes for fatal illnesses will be deleted, and the blind will see. Disability will become a thing of the past. But when doctors and scientists are given free rein to measure and fix infants, it’s not clear where they’ll draw the line between different and sick. Where exactly does the desire for normal start to infringe on diversity?

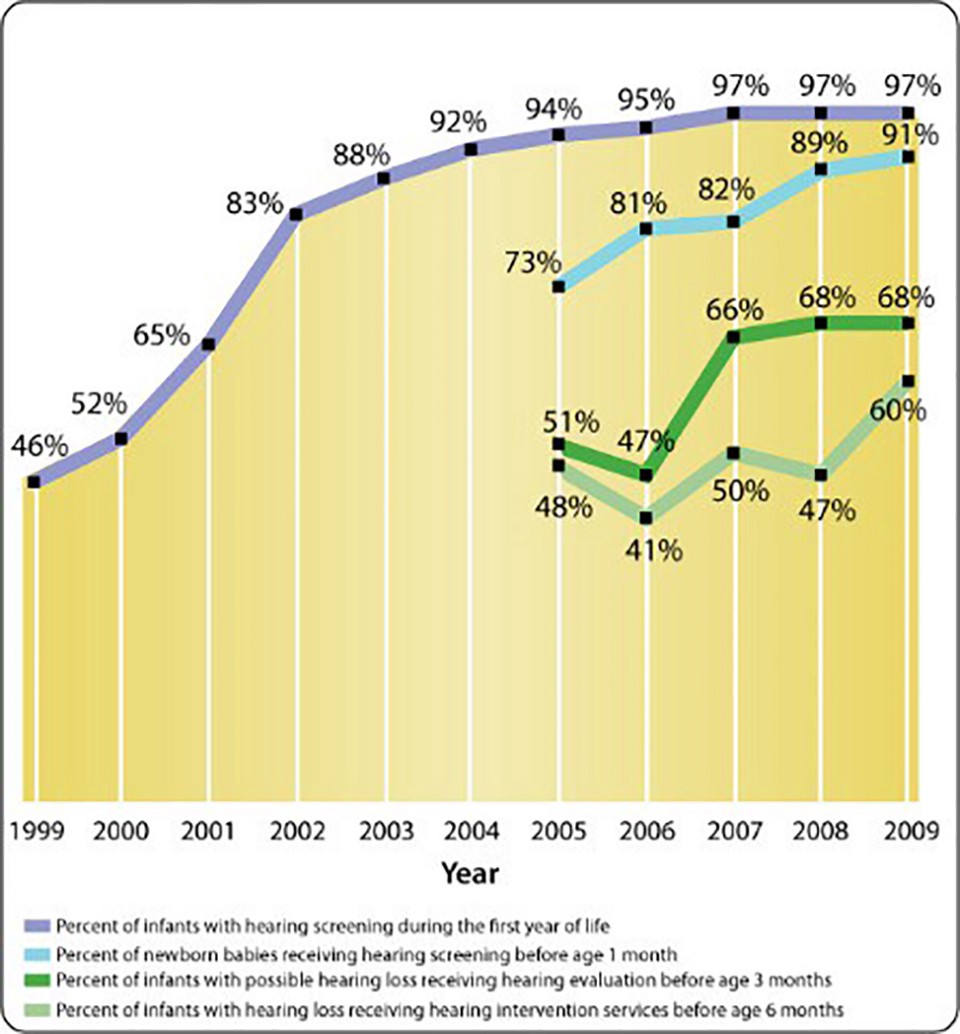

A 1988 federal commission found that profoundly deaf children were not being diagnosed until an average of two-and-a-half years old. In 1993, the National Institutes of Health endorsed testing for all infants. Now over 95 percent of newborns are screened within the first year, the vast majority before they leave the hospital, and hearing loss is the country’s most frequently detected “birth defect.” With near-universal testing and some encouraging success with early use of cochlear implants, medical science is hoping for a future without deafness.

The official line is that the brain is only capable of so much, and the struggle for neural territory between the visual and auditory systems is zero-sum.

I put the term “birth defect” in scare quotes because there’s a debate about whether the idea should be applied to deaf infants at all. In the early 1990s, as cochlear implant makers started presenting their products as an answer to deafness, Deaf activists and their allies warned of a plot to destroy their community, culture, and language. A decade and a half later, it’s becoming clear just how prescient these Deaf activists were — and how badly they lost the battle to define their identity for themselves.

In her new book Made to Hear: Cochlear Implants and Raising Deaf Children, University of Connecticut sociologist and sign-language interpreter Laura Mauldin takes us through the early intervention program at a New York hospital, as parents and their diagnosed children navigate a new aural reality. For the families whom our medical system is designed to help — upper-class, white, American-born — infant deafness has an answer.

Made to Hear: Cochlear Implants and Raising Deaf Children. (Photo: University of Minnesota Press)

Cochlear implants were a flashpoint for Deaf identity debates in the 1990s. The device bypasses much of the auditory system and sends signals from an external microphone directly to the nervous system via implanted electrodes. It’s a bionic ear, a human sense reconstructed via electronics. The manufacturers put out inspirational videos where, with the flip of a switch, a deaf child begins to hear.

Only 10 percent of deaf infants are born to deaf parents, so the market for implants is primarily hearing adults, particularly mothers — fathers didn’t play primary roles in any of the cases Mauldin observed. “The demand for the product is not coming from babies,” she says, “so the industry thinks of itself as supporting mothers, and markets the implant to them as opportunity for their child.” It’s understandable that hearing parents have a hard time imagining how a deaf person could live a happy life, but less so why no one tries to help them manage it. Instead, they’re channeled toward an implant as soon as possible, the professionals dangling their chance for a normal child in front of them the whole time.

If the mother navigates the various suitability tests, she discovers that the inspirational implant videos are misleading. Learning to hear is not just a matter of plugging a microphone into the brain. Implanted children have to be trained in using these signals, not to mention the devices themselves. The implant relies on different microphone settings for different situations — a classroom versus a busy street, for example — and a deaf infant has very limited ways to communicate feedback. The process of mapping these settings “relies on the mother’s ability to be extremely engaged with her kid in a very particular way,” Mauldin says. “It requires a lot of labor, time, and resources.”

The American medical establishment can’t manage to treat deafness without disdaining the Deaf.

Besides implants, sign language has become a point of conflict between the Deaf and audiology (hearing-loss treatment) communities. American Sign Language has knit the national deaf community together, but, according to Mauldin’s research, mainstream audiology now views visual communication as a threat to the fragile development of speech and hearing competency in implanted children. The official line is that the brain is only capable of so much, and the struggle for neural territory between the visual and auditory systems is zero-sum.

Mauldin doesn’t offer an explicit Deaf critique of the cochlear implant industry, but it’s hard not to fill in the blanks when it comes to the assault on sign language. Preventing a group from transmitting its primary mode of language to the next generation is a hallmark of eliminationist strategy. It’s what you do when you want to wipe an identity group off the Earth. The right of deaf children to learn in sign language is included in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities — which the United States has signed but not ratified — but at what age, at what point in the process, does a deaf child born to hearing parents have the opportunity to invoke such a right?

Audiology professionals exert intense pressure to dissuade parents of implanted children from using visual communication under any circumstances. They more or less threaten mothers: Implants don’t fail, but kids and families sometimes do. Not only do they forbid sign language, some even tell parents to cover their mouths when talking to their deaf toddlers. “Sign is sometimes seen as separatist, as a decision to withdraw from the broader culture,” Mauldin says. “To be part of the culture you have to speak English.” The American medical establishment can’t manage to treat deafness without disdaining the Deaf.

(Chart: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders)

Identity conflicts never happen in isolation. The vast majority of medical professionals throughout the diagnostic and implant process (with the exception of surgeons) — screeners, audiologists, language pathologists — are highly educated white women, and Mauldin suggests this homogeneity changes how the industry deals with patients. The ideal candidate for an implant is from a family that mirrors the hospital: white, English-speaking, educated.

Under this therapeutic regime, households that have a strong internal “culture” are generally considered an obstacle to success for deaf children. “The clinic I observed looked at patients very holistically,” Mauldin says. “On its face, seeing someone in the larger social structure is progressive, but part of their goal is to find the most compliant candidates.” In a 2012 review of the scholarship on implants in children, Julia Sarat of the University of Melbourne Department of Audiology found richer families with fewer children produce the best hearing outcomes, making them (in general) the most suitable candidates. How do we expect these professionals to handle social inequality when it acquires medical significance?

Potential compliance or suitability is a tricky thing to measure, and with a homogenous group doing the evaluating, it’s hard to exclude and correct for stereotypes and prejudice: Working-class mothers can’t be trusted to keep their child’s device charged, and the system is set up not to promote speech per se, but spoken English; the suitability evaluators are skeptical of any family with another first language. And as resources are routed away from ASL services, deaf children who don’t receive an implant are left with an impoverished infrastructure of support.

Deaf critique demands that Deaf people be understood through the lens of human diversity, not as broken machines. While it’s true deafness poses unique challenges in this society, as bioethicist Rob Sparrow points out, “the key phrase in this sentence is ‘in this society.’” If we make it medicine’s prerogative to optimize infants for this society, how will we ever come to imagine a better one?

With non-verbal communication advancing every day — in no small part thanks to the contributions of hearing-impaired people themselves — it may be the easiest time ever to live as a Deaf American. One of the earliest complaints about cochlear implants is that implanted children never get a chance to choose; the implant-industrial complex does its best to remove the idea of choice altogether. There are only the suitable and the unsuitable, the fixed and the malfunctioning. That’s a dangerous precedent, and a loss for society that we may never truly understand.

||