In early January, shortly before leaving office, Julián Castro, President Barack Obama’s secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, announced a small cut to the Federal Housing Administration’s mortgage insurance premium rates. Castro said the cut, which was expected to save FHA-insured homeowners about $500 a year on average, came in response to mortgage interest rates, which have been on the rise recently. Though the announcement was applauded by advocates representing both the housing industry and low-income Americans, conservatives expressed alarm that the move might threaten the financial stability of the FHA Mortgage Insurance Fund. Shortly after President Donald Trump was inaugurated, his administration seized the chance to scrutinize the cut.

On January 20th, the Department of Housing and Urban Development announced it would suspend the premium rate cut, which was due to go into effect on January 27th. The actual effects of the Trump administration’s reversal are a topic of some debate. The FHA insures mortgages for many lower-income and first-time home buyers, on terms that these buyers might not be able to find elsewhere. FHA-insured buyers, for example, can obtain mortgages with lower credit scores or with much smaller down payments than a bank would demand of non-FHA-insured buyers. While a number of housing experts concluded that the proposed rate cut (and thus its subsequent suspension) was too small to dramatically alter people’s home buying decisions, others argued that the suspension harmed low- and middle-income Americans.

William Brown, the president of the National Association of Realtors, said the reversal would translate into higher costs for at least 750,000 existing homebuyers, and might prevent 30,000 to 40,000 new buyers from purchasing a home in 2017. The Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, released a statement saying the suspension “puts the dream of homeownership farther out of reach for millions of hardworking Americans.”

Interestingly, given the almost total lack of attention paid to housing during the campaign, it was not the first time the Trump team had run afoul of those particular industry groups representing housing, lenders, realtors, and so forth. Late last year, Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin started a bit of a firestorm when he said on CNBC that the Trump administration planned to cap the mortgage interest deduction, the tax break that allows (mostly wealthy) homeowners to deduct the cost of mortgage interest from their taxable income (thus reducing their tax bill). (The White House quickly walked back the comments.) Mnuchin isn’t alone in his concern over the boondoggle that is the mortgage interest deduction: During the primaries, then-presidential nominee (and current HUD secretary) Ben Carson actually called for the outright elimination of the deduction.

Carson and Mnuchin are also not the only Republicans to question the value of the mortgage interest deduction. While the GOP’s tax reform plan doesn’t entirely eliminate the deduction, it significantly reduces the tax perks of home ownership. The plan already has the housing industry up in arms. In early January, Politico reported that the National Association of Realtors, the National Association of Home Builders, and other industry allies are “preparing a battle to preserve the strength of what has always been untouchable in the tax world: the mortgage interest deduction.”

“We’re looking at the current draft plan as an assault,” Jerry Howard, the CEO of the National Association of Home Builders, told Politico. “By raising the standard deduction you put money in people’s pockets, yes, but you’re not encouraging them how to use the money.”

Likewise, Jamie Gregory, the vice president of the National Association of Realtors, said: “Congress decided 100 years ago that we wanted to encourage people to buy a home. Expanding the standard deduction takes away that incentive.”

Gregory is correct: The government’s efforts to encourage home ownership date at least as far back as 1918 when the Department of Labor collaborated with industry groups on a large public relations campaign, called “Own Your Own Home,” which sought to convince renters of the financial and social benefits of owning a home. As the century wore on, and particularly during the Great Depression, the federal government crafted a variety of policies inserting itself into the housing market. Today, in addition to the mortgage interest deduction, the United States government guarantees mortgages for low-income families that might not otherwise be able to get credit (through the aforementioned FHA), provides grants for housing rehabilitation, and provides liquidity to the mortgage market through government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

“We are encouraging home ownership for reasons that no longer make sense.”

And political support for home ownership transcends parties: Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama all gave major speeches on the topic during their presidencies. Broadly speaking, the argument for government policies that specifically encourage home ownership is premised on the theory that home ownership produces better outcomes — for both families and society at large — than renting.

“Homeownership, in short, is valued and promoted by government: it is considered good for the buyers, good for their communities, and good for the country,” housing scholars Nicolas P. Retsinas and Eric S. Belsky wrote in 2001. “It is not far behind motherhood and apple pie as an American symbol. At least in the abstract, nobody questions this American icon.”

Surprisingly, however, given how much money the federal government spends subsidizing home ownership, the actual evidence on this is a bit thin. “Up to about 15 years ago, there really was very little research done on that question,” says Donald Haurin, an economist at Ohio State University who studies housing. “One thing we noted [when I started studying this] was that government was, through deductions or tax credits or direct subsidies, doing a lot to support home ownership. And it was kind of curious that all money was being spent and, unlike education, which is constantly studied, people just sort of believed that home ownership was good.”

In recent years, however, prompted by both the disastrous housing bubble and crisis of 2008 and the rising cost of housing in many cities, both politicians and researchers are starting to ask if it’s time to decouple home ownership from the American dream.

Efforts to rigorously identify the effects of home ownership have been hampered by a selection bias problem. Researchers can’t tell if it’s home ownership itself that produces different outcomes than renting, or if people who choose to buy a home are just inherently different from people who choose to rent. In general, though, the research suggests that homeowners perform more maintenance on their properties, are more likely to vote, and are perhaps modestly more likely to be involved in civic institutions (neighborhood organizations, community groups, etc.).

There is also some evidence that children who live in owner-occupied housing fare a bit better academically than their peers living in rental housing. In an article published in the Journal of Urban Economics, Richard K. Green and Michelle J. White found that children of homeowners complete more years of schooling, and daughters of homeowners are less likely to have children as teenagers. And in a new, unpublished working paper, Haurin and co-authors David M. Blau and Nancy Haskell found no short-term effects of living in an owner-occupied home on cognitive achievement and behavior problems, but that it “is positively associated with the child’s subsequent educational attainment and work experience, and is negatively associated with teen pregnancy, criminal convictions, and the likelihood of being on welfare.”

On the flip side, researchers point out that home ownership may produce some negative effects as well. It limits economic mobility, which is bad news for the labor market at large and for individual families during economic downturns. And it may also inspire homeowners to advocate for the kinds of things that are good for them, but bad for everyone else — i.e. tougher zoning laws that drive up the price of housing. In a 2013 paper in Social Forces, the sociologist Brian McCabe found that home ownership increases civic participation (by a small amount), but cautioned against simplistic interpretations of his findings. Just because homeowners are civically active doesn’t mean that all that civic activism is good for society at large.

The economists Ed Glaeser and Jesse Shapiro expressed a similar concern in a 2003 paper on the value of the mortgage interest deduction:

The homeowners’ desire to keep property values up has a dark side, however. Homeowners, not renters, have been more aggressive in fighting racial integration, especially in the 1960s and 1970s. More recently, homeowners have spearheaded the movement to limit new housing supply, which has artificially inflated housing throughout the United States. Essentially, as owners have organized, they have started to act like local cartels, restricting new entry into the market: the downside to having individuals who have incentives to keep price up.

The biggest blow to the mythology of home ownership, however, came in the form of the housing crisis of 2008. For decades, policymakers had argued that home ownership was the surest route to economic stability, but the crash destroyed the wealth of countless low- and middle-income homeowners.

“I think the myth was oversold, and it became more disastrous during the foreclosure crisis,” says Barbara Sard, the vice president for housing policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank. “The belief that home prices always go up has never been correct, and it particularly has never been correct in certain neighborhoods.”

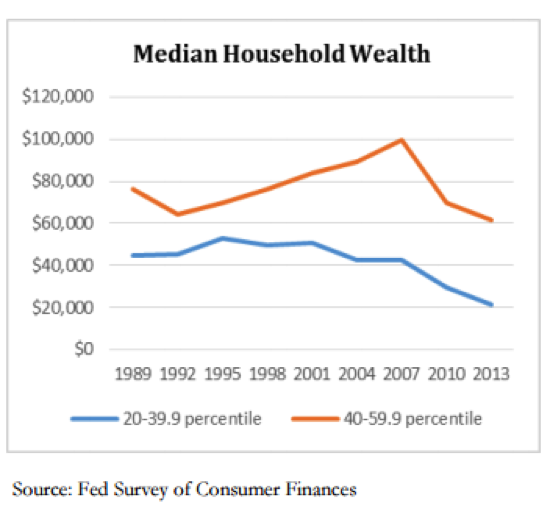

“We certainly have not been building wealth for lower-income and middle-income families,” says Ed Pinto, the co-director of the International Center on Housing Risk at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “They have less wealth today than they did 25 years ago.”

The chart to the left, from an article for AEI that Pinto wrote back in 2015, illustrates median household wealth for middle-income families over the last several decades.

The housing crisis had particularly devastating effects on low- and middle-income minority homeowners, who were disproportionately (and illegally) funneled into sub-prime mortgage products (even when they could have qualified for prime products) and whose neighborhoods were also hardest hit by the crisis. “One-in-eight FHA borrowers over the last three years, from 1977–2014, lost their home,” Pinto says. “That understates what it was in minority neighborhoods. We know that, in minority neighborhoods, it’s more like one-in-seven or one-in-6.5.”

Mechele Dickerson is a professor at the University of Texas–Austin School of Law who studies housing. In recent years, she has argued that low-income minority families would be better off forgoing home ownership in favor of renting in neighborhoods with better schools.

“No, you don’t need to own a home,” Dickerson says. “What you need to do is go and find the best school district around you and figure out how can you live for 18 years in that school district. And, at the end of the 18 years, if you want to buy, then fine, then you buy.”

Dickerson’s stance may not always be a popular one, a fact she suspects is in large part due to concerns about minorities missing out on the benefits of home ownership, a particularly touchy topic given the country’s ugly history of redlining. In response, she points out that an ample body of evidence now demonstrates that, even in non-crisis times, homes in communities of color are valued less and appreciate less. Above all else, Dickerson believes that the country’s obsession with home ownership just doesn’t make financial sense for many families, given current economic realities.

“I would say we are encouraging home ownership for reasons that no longer make sense,” she says. “A 30-year mortgage makes perfect sense for people who are going to be in the same house for 30 years and have the same job for 30 years. But we’re never going back to a time where you graduate for high school, marry your high school sweetheart, get a job working at a plant, move up and get predictable promotions at the plant, and then retire from that plant after 35 years.”

So what does this all mean for what U.S. housing policy should look like going forward?

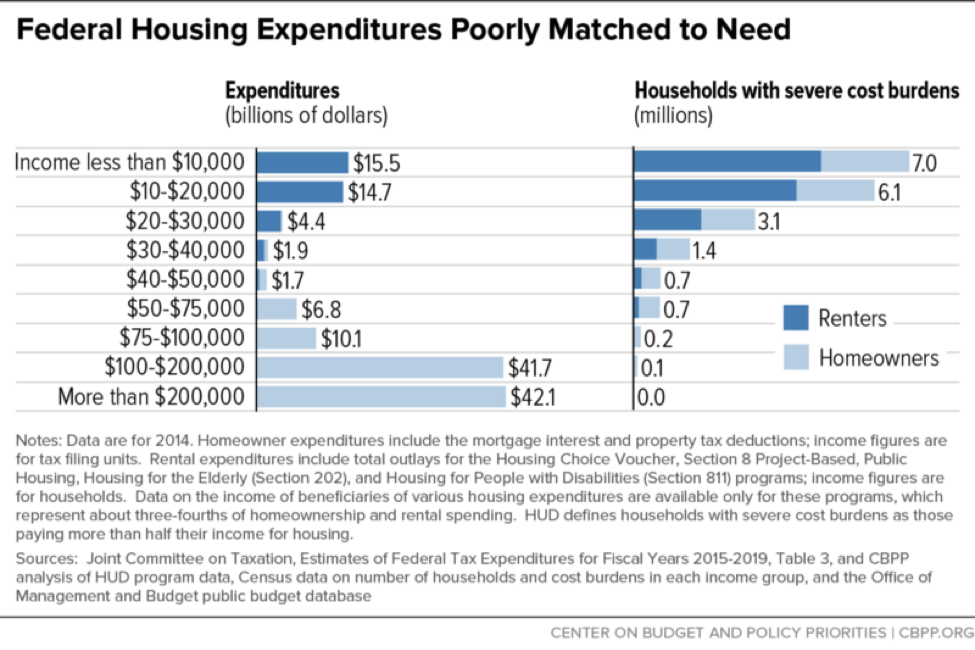

For starters, the researchers and policy experts we spoke with were unanimous in their belief that current federal spending on housing is poorly targeted, in large part due to the enormous amount of money that the government spends on the mortgage interest deduction, which mostly benefits wealthy homeowners. In 2015, the U.S. government spent approximately $190 billion on housing assistance for Americans.

“Overall, about 60 percent of federal housing spending for which income data are available (counting both tax expenditures and program spending) benefits households with incomes above $100,000,” wrote Sard and Will Fischer in a chartbook for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “The 7 million households with incomes of $200,000 or more receive a larger share of such spending than the more than 55 million households with incomes of $50,000 or less, even though lower-income families are far more likely to struggle to afford housing.”

The chart below, from Sard and Fischer’s chartbook, illustrates just how much the government currently spends on subsidizing housing for wealthy households as compared to poorer households facing housing cost burdens:

Government spending on housing is also disproportionately targeted toward homeowners, as the chart below (also from the CBPP) demonstrates:

Both of those things, experts say, need to change. Government spending should be targeted at low- and middle-income families, not high-income families, and it should be focused on making housing affordable for both renters and owners.

“I no longer think we should encourage people to own homes,” Mechele Dickerson says. “I think the U.S. policy should be to encourage affordable housing, for both renters and owners. This notion that the only people we should be concerned about are homeowners, or the only major tax credits should be for homeowners, is wrong now.”

There are a number of proposals floating around to help renters — a renter’s tax credit or an expansion of housing voucher programs (which currently serve far fewer families than need assistance) could both help low- and middle-income renters close the gap between their income and the costs of housing. Crucially, however, experts also agree that cities around the country need to figure out how to build more affordable housing units in decent neighborhoods. And that is often easier said than done in the face of local opposition to affordable housing.

“In terms of the access to decent neighborhoods with affordable home ownership or rental, we’ve got major challenges in terms of barriers created by local zoning,” Sard says. “That’s been a really hard policy nut to crack, but I think there is a growing consensus from both sides of the ideological spectrum that we really do need to solve this problem.”