In a rumpled suit jacket and faded jeans, Giles Slade stands atop an earthen levee and looks out over a vast expanse of water. It’s mid-November, and the Fraser River runs gray and glasslike into the Salish Sea. Overhead, airplanes flash through low clouds, descending into Vancouver International Airport. To our backs is the city of Richmond, British Columbia, splayed out on the table-flat delta, the majority of its homes and buildings set just a few feet above sea level. “You can begin to see the scale of our problems from right here,” he says, waving a hand across the gray swath of water and sky.

Slade, 62, resembles a svelter John Goodman. He wears hip glasses, and his sentences are delivered in a calm, professorial baritone. But his mellow demeanor belies a deep anxiety, rooted in the threats posed by climate change to the Pacific Northwest, and to his flood-prone town of 190,000. He’s channeled that angst into a gripping work of non-fiction titled American Exodus(the title is an homage to An American Exodus, a book about the Dust Bowl published in 1939 by economist Paul Taylor, with photographs by Dorothea Lange). Slade’s book offers a disaster-movie account of the days ahead for North America — a future defined by epic drought, megafires, colossal hurricanes, rising seas, and the massive human migrations that such events are likely to spawn.

The idea for the book dates back to the late 2000s, when Slade began to note numerous climate-driven migrations happening in the developing world. “There was a lot of material on climate migrations in Somalia and some other parts of the world,” he recalls. But at the time he could find no resources exploring how climate change might affect human populations in North America. Could things here reach a sort of climatic tipping point, Slade wondered, forcing people to move suddenly and in large numbers? “I was surprised to find that there were things that were already happening,” he says, mentioning Mexico and Central America, where prolonged drought, combined with violence and economic and political instability, has triggered the movement of tens of thousands of people northward over recent decades.

“There is a notion out there that climate change is not going to really be that big of a deal in the Pacific Northwest, which of course is not true.”

As he pored over the climate data, he became obsessed with one particular scenario. With drought intensifying in California, Slade envisioned a new Dust Bowl situation, in which tens of thousands of people evacuate the drought-ravaged southwestern United States and stream into the Pacific Northwest. Would the Oregon state line become like the U.S.-Mexico border? “That scenario,” Slade says, “seems closer and closer every day.”

For years, publishers weren’t interested in his ideas. “I was told by several U.S. publishers that climate change wasn’t happening,” he says. “Others viewed it as a boring disaster book with an unlikely prediction.” Things changed in October of 2012, when Superstorm Sandy blasted New York, forcing thousands of evacuations from the U.S.’s most populous and high-profile city. “I got a call and an offer the same week.”

One might be inclined to dismiss his predictions as the products of an overactive imagination (Slade spent his early years writing military novels for Harlequin Books) — that is, if the book weren’t so meticulously researched and reported. And then there’s the fact that Slade is no longer the only one talking in such stark terms about climate-driven migrations.

“What we’re seeing in Europe now with mass migrations, that will happen in California,” declared California Governor Jerry Brown last fall at a press conference. “Central America and Mexico, as they warm, people are going to get on the move.” In a recent talk to U.S. ambassadors, Secretary of State John Kerry painted a similar scene: “There’ll be climate refugees that all of you will be coping with at some point — if not now, in the not-too-distant future.”

Recent data underscores these predictions. A study from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters estimated that, between 1994 and 2014, as many as 3.5 billion people worldwide were affected by flooding and drought. More recently, a study in the journal Science Advances estimated that four billion people — roughly two-thirds of the entire human population — experience severe water shortages for at least one month out of every year.

And yet, here in the U.S., we tend to think of severe climate disruption as something that is happening elsewhere. According to recent Gallup polls, 60 percent of Americans accept that climate change is happening, and 57 percent believe that it is caused by human activities — but only 36 percent believe it poses a threat to their way of life. If we think of a climate migrant or climate refugee at all, it is likely a resident of the South Pacific island of Tuvalu, which may disappear completely due to rising sea levels; or a villager from Africa’s Sahel region, one of many forced from the arid countryside in the wake of successive droughts.

Meanwhile, the climate is painting a different picture for North America. Storms are intensifying. Droughts are deepening. The sea level continues to rise. In 2012 alone, the costs of climate- and weather-related disasters in the U.S. were over $100 billion, according to the White House Climate Action Plan. Follow the trajectory, and Slade’s vision of a great American exodus seems quite plausible.

The year is 2025. Across the world, water levels have risen faster than any climate models predicted. The Marshall Islands and Guam, both U.S. protectorates, are under water. As is most of Hawaii. Other parts of the U.S. have experienced rapid desertification. Las Vegas has been evacuated, and California’s once-fertile Central Valley is a wasteland where only buzzards and criminals languish.

This was the scenario laid out for a role-playing game hosted by the Seattle- based World Affairs Council in 2014, in which a panel of civic leaders entertained the possibility of having thousands of refugees stream across the Oregon border, seeking that most precious resource in a time of drought: water. Nathan Sharpe, a spokesperson for the World Affairs Council, affirms that the language they chose was intentionally provocative: “We wanted people to think big.”

To promote the event, the council posted a mock newscast on YouTube in which two female newscasters describe the re-naming of a small town on the Washington coast “Little San Diego,” and the future mayor of Seattle (none other than Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson) issuing a stern proclamation on water theft. “If Seattle can’t crack down on illegal water trading,” says the newscaster, “the city will have no choice but to move all public park reservoirs underground.” (In spite of the provocative rhetoric, Sharpe told me that the discussion was measured — neither the panelists nor the sponsoring organization truly believed that legions of climate migrants were bound for the region any time soon.)

Two years earlier, in 2012, the Oregon Department of Transportation issued its Climate Change Adaptation Strategy Report cataloging the various risks posed by storms, fires, landslides, and flooding to the state’s roadways. But on page 10, the report considered a different sort of flood: “Oregon may see an increase in population, due to an influx of ‘climate refugees’ or more generally people moving to a more desirable climate.” The idea of a climate-triggered mass migration had begun to take hold in the region’s collective imagination.

Other respected voices joined the chorus. In 2014, Cliff Mass, a noted professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington, told the New York Times that, due to rising average temperatures, Washington’s largest wine-producing regions, in the eastern part of the state, could soon supplant California’s Napa Valley. “People are going crazy putting in vineyards in eastern Washington right now,” he told the Times. Greater acreages of grapes mean not only more wine, but also more agricultural jobs.

Mass, who has built a reputation calling out what he sees as alarmist views on climate, speaks bluntly about the possibility of climate migrants to the region. He believes that the Pacific Northwest will be better insulated than other regions against climate change, which will present a different set of problems for its residents. He poses a question undoubtedly on the minds of many: “How do we keep the Californians out?” His answer comes in the form of an image on his blog: a tall fence topped with concertina wire.

Complicating matters is the region’s unprecedented growth. “We are in a boom that has been likened to the Gold Rush days,” says Lara Whitely Binder of the University of Washington-based Climate Impacts Group. “There are cranes everywhere. Over the last few years we have seen growing concern over housing prices, rental prices, and traffic jams. People are wondering, ‘What are we going to do when all the climate refugees start pouring in?’”

In the arid Southwest, nearly 200 feet up the wall of a narrow canyon in New Mexico, stands a group of imposing structures built into a cave-like alcove, their walls and ceilings blackened with centuries of soot. Eight hundred years ago, archaeologists say, what is now Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument was home to probably 40 to 60 people. The settlement is believed to have been a northern outpost of the Mogollon people, one of three culturally distinct groups, including the Hohokam and Ancestral Puebloans, or Anasazi, who once inhabited the canyon country of the U.S. Southwest.

Then, in the late 1200s, a great drought struck the Four Corners region. As rainfall dwindled, the small-scale agriculture practiced by the peoples of the Southwest failed. Signs of famine and internecine warfare, including charred buildings and desecrated human remains, are found in archaeological sites across the area. “In some places … tensions erupted into acts of terrorism, and factions attacked and burned whole villages,” wrote Karen Gust Schollmeyer, an Arizona-based archaeologist. “Assailants killed men, women, and children, their bodies disposed in ways that signaled enmity, as well as utmost disrespect for those people, their religious buildings, and the symbols of their past.”

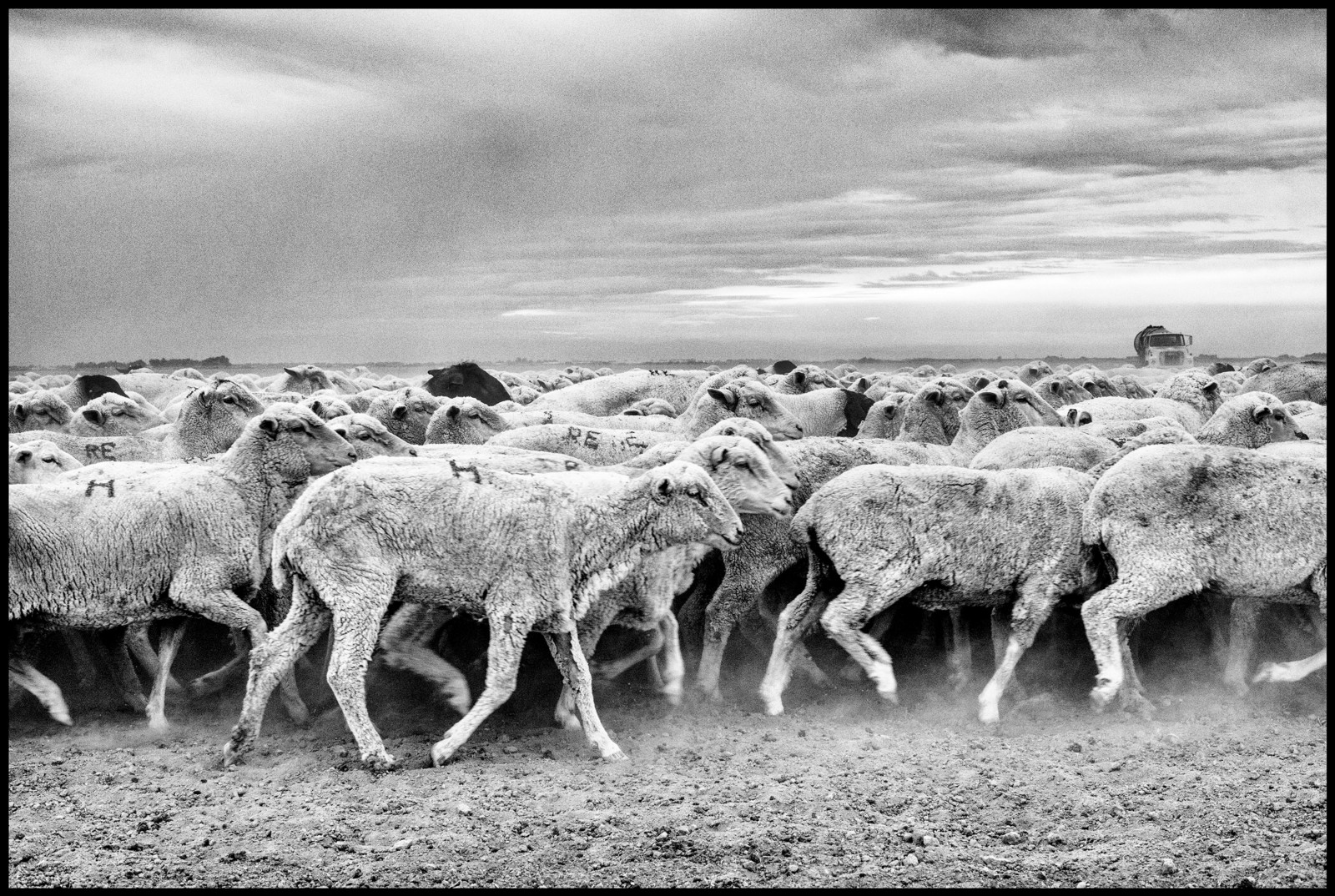

(Photo: Matt Black)

A common refrain is that the people of the Southwest basically “disappeared” around seven centuries ago. But ask a member of the Tohono O’odham, Pima, Hopi, Zuni, or any number of tribes on the southern side of the U.S.-Mexico border — people who are believed to share linguistic connections with these earlier inhabitants — and they will tell you that these tribes did not simply vanish. Rather, they moved. The Anasazi, Mogollon, and Hohokam, for all purposes, are their ancestors.

They were by no means the first to move. Throughout history, shifts in climate have caused groups of people to undertake dramatic relocation efforts. Perhaps the best known of these journeys took place between 12,000 and 15,000 years ago, when Ice Age hunter-gatherers migrated across the Bering Land Bridge — an isthmus exposed by retreating ocean levels during the Ice Age — into today’s Alaska.

Venture further back in time, to between roughly 135,000 and 900,000 years ago, and a series of megadroughts during the late Pleistocene may have parched the African tropics, causing human populations to crash. Then, around 70,000 years ago, the climate seems to have gotten wetter — a period that archaeologists say corresponds with the first major human migrations out of our evolutionary cradle in Africa. These human migrations may have happened in waves, or in one fell swoop. (And one new idea, based on stone tools discovered on the Arabian Peninsula by researchers at the University of Tübingen, suggests the exodus may have begun as far back as 100,000 years ago.)

Whatever the timeframe, the journey out of Africa was not merely a long walk out of a climatically unstable region. New evidence suggests it was a migration contingent on favorable conditions elsewhere. The obvious exit route was across the Arabian Peninsula — today one of the planet’s most forbidding locales. “Although now arid, at times the vast Arabian deserts were transformed into landscapes littered with freshwater lakes and active river systems,” according to the authors of a study published in the journal Geology. In other words, the shifting climate appears to have provided an ephemeral lifeline into the Near East.

One of the largest human migrations underway today (and doubtlessly the most fearful) is the one happening in Syria. Since civil war erupted in 2011, more than 6.6 million people have been internally displaced, and more than four million have fled the country, seeking asylum in refugee camps in Jordan and Turkey and farther north in Europe. While the country’s brutal civil war is often presented as the cause of this mass migration, a study published last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that it may be rooted in an earlier environmental crisis, one linked to land degradation and long-term drought in the Fertile Crescent.

Like other Mediterranean regions, Syria typically receives nearly all of its precipitation during a six-month span over the winter. But between 2006 and 2010, rain and snow failed to materialize in the high country, and the Tigris and Euphrates rivers — lifelines in an unforgivingly dry land — dwindled to a fraction of their normal flow.

The scenery seems to reflect the suffering. As groundwater has been siphoned away, the land itself has begun to slump.

It was the most severe drought on record in the last century, says Colin Kelley, a senior research fellow with the Center for Climate & Security and lead author of the report. But it wasn’t just a natural anomaly. By comparing previous droughts with this one, Kelley and his team determined that a drought this severe was made two to three times more likely by human influences on the climate. Decades of governmental mismanagement of land and water had compounded the prolonged lack of precipitation. When Bashar al-Assad took power in 2000, he accelerated the policies of his forebears, expanding grazing and allowing large farms to control massive quantities of the country’s already scarce surface water. To compensate, farmers on the losing end of these policies dug hundreds of wells, rapidly drawing down the region’s aquifers.

As Syria’s water dwindled, the country’s wheat crop, a linchpin of the national economy, was decimated, dropping to roughly half of its pre-drought levels. “They went from being a net exporter of wheat to a net importer almost overnight,” Kelley says. “People started to give up. They began to pick up their families and go to the cities in the west.”

Populations in cities such as Aleppo and Homs exploded as rural migrants crowded into slums. The hundreds of thousands of people pouring out of the countryside and into cities joined the roughly one million Iraqi refugees who had already fled to Syria during the U.S. occupation. The rapid influx of unemployed people to cities created a politically volatile situation, Kelley says, one that helped foment the uprising of 2011, a thought echoed by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, who wrote, in 2013, “Young people and farmers starved for jobs — and land starved for water — were a prescription for revolution.”

Kelley is hesitant to say climate was the ultimate cause of the conflict, but he is certain it played a significant role. He views climate as a single slice in a larger “pie of resilience,” which also includes factors such as economics, political stability, and social cohesion. You might be able to tolerate the loss of one or two of these slices, “but take a certain one away and that might trigger a person or a whole group of individuals to migrate,” he says. “You never know which one of these factors is going to drive it over the edge.”

The surreal greenery of fruit and nut trees provides a stark contrast to the beige and arid hillsides surrounding California’s Central Valley. The green is the product of a vast irrigation network that has transformed this semi-arid basin into the country’s most productive agricultural landscape.

But today, after five years of drought, the beige is on the march. Topsoil has been stripped bare, and thousands of acres of fruit trees have been reduced to skeletons. Severe declines in Sierra Nevada snowpack have diminished the volume of water in the state’s largest reservoirs to a fraction of their total capacity. Those reservoirs feed a complex network of canals and aqueducts, which, in turn, supply California’s largest farms, cities, and industries. Over the last few years, to make up for the deficit of surface water, farms and towns have heavily tapped into the Central Valley’s groundwater. In many regions, wells now extend more than 1,000 feet below ground, probing the depths for “fossil” water deposited millennia ago. The scenery seems to reflect the suffering. As groundwater has been siphoned away, the land itself has begun to slump, with some parts of the valley sinking at a rate of two inches per month.

As the green disappears, so does the Central Valley’s economy and, quite possibly, large numbers of its people — many of whom had come to the Central Valley after fleeing droughts elsewhere. Of the estimated 2.5 million people who fled the “black blizzards” of the Dust Bowl between the early 1930s and 1940, roughly 200,000 arrived in California’s great agricultural basin. A larger and more recent mass migration brought an estimated 7.5 million Mexican immigrants to the U.S. between 1990 and 2010; more than one in three of these migrants settled in California, with large numbers seeking work as agricultural laborers in the Central Valley. Many of those who entered this country, often illegally, were not merely seeking una vida mejor, but escaping an economic meltdown brought on by both the North American Free Trade Agreement and a prolonged drought. At the drought’s zenith, in the northern states of Durango, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Nuevo León, there were reports of eight to 10 farms being foreclosed upon daily. (Rural Migration News, a University of California-Davis publication that examines issues affecting migrant farmworkers, compared the scale of the Mexican drought to the U.S. Dust Bowl.) In 1995, the Mexican government declared a state of emergency, but the drought would grind on for another decade.

Today, California’s great agricultural basin looks more and more like the drought-ravaged landscapes it once provided sanctuary from. Last year over one million acres of farmland were fallowed, more than double the unplanted acreage at the beginning of the drought in 2011. Unsown land equals job losses. According to a report from UC Davis’ Center for Watershed Sciences, the Central Valley’s agricultural sector lost over 10,000 jobs in 2015 alone.

“Those losses are concentrated in certain parts of the Central Valley,” says Josué Medellín-Azuara, an associate research engineer at the Center for Watershed Sciences, underscoring that unemployment and drought severity go hand in hand. “Agriculture represents a big proportion of the local income and employment, so this is a very big deal in the places where it is happening.”

One of those places is Tulare County, near Fresno — often called the epicenter of the drought. Not only have workers been laid off, residents have seen wells run dry. Those who still have water coming from the taps often cannot drink it; local aquifers are badly contaminated with nitrates, pesticides, and a host of other industrial pollutants. Some of the towns experiencing the worst groundwater problems sit adjacent to the concrete arteries funneling millions of gallons of surface water from northern California to large cities and farms in the southern reaches of the state, a marvel of engineering separating California’s hydraulic haves from its have-nots.

In years of reporting in these communities, I have heard the same story repeated. People must choose to either use the contaminated municipal supplies, or spend large amounts of their already scant wages on bottled water. Last October, the California Department of Housing and Community Development earmarked $11 million in funds to provide alternate water supplies and temporarily relocate 500 households whose wells have gone dry — a tiny fraction of the overall population affected by the drought.

For many in the region faced with dwindling access to drinking water and rising unemployment, there is but one solution: Move. While no comprehensive data yet tracks these migrations, one indication that this movement is underway is that school districts serving large numbers of children of migrant farmworkers have rapidly lost students. But where have they gone? In July 2015, Mexican Consul General Alejandra Garcia Williams announced that the Mexican government would offer certain drought-stricken migrant farmworkers financial assistance — and even pay their airfare back to Mexico. It’s not clear whether any families have taken advantage of this offer. Others may have left the region for the less drought-prone Salinas Valley, according to Medellín-Azuara. I also heard whispers of another exodus, one leading from California to the traditionally wetter agricultural regions farther north.

Thousands of itinerant pickers are already accustomed to cobbling together year-round work by “chasing the harvest,” making a circuit between the citrus groves of the Central Valley and the fruit orchards and berry fields of Washington and Oregon. Nowadays, many are deciding not to return to California, taking up permanent residence in the Pacific Northwest.

It’s late February. The hillsides are green and the fields are accented with the yellow blooms of daffodils. The snowcapped cone of Mount Baker towers over the tidal lowlands of the Skagit River. In a few weeks, the farms will take on even more color as the region’s tulips bloom and the green shoots of berry plants emerge from dark rows of soil. Celestino Santos, 32, lives in an apartment complex on the eastern outskirts of Mount Vernon, Washington, a quiet farming town of 32,000 located an hour north of Seattle. Before coming to Mount Vernon, Santos toiled for 10 years as a strawberry picker in Central California. He describes the backbreaking work in the berry fields — beginning at 7 a.m. and ending at 5 p.m., struggling to meet strict weight quotas. After the seasonal strawberry harvest was over, he’d depart Central California for coastal Washington to pick cucumbers. In the late fall, at the end of the cucumber harvest, he’d return home to California.

Then came the drought. Spring rains failed, and summer temperatures soared. “People were passing out in the fields,” Santos says. “It was too hot to work.” In 2012, he and dozens of his co-workers fled northward seeking refuge. Some went to Oregon; others traveled to Washington.

Thousands of California workers may have made a similar migration, says Edgar Franks, an organizer for Bellingham-based Community to Community Development, a non-profit organization that advocates for migrant farmworkers. Some have gone to Oregon’s Willamette Valley or the Yakima Valley in eastern Washington. Others have gone farther north and west, seeking work in the berry and tulip fields of Skagit County, which stretches along the verdant western slope of the Cascade mountains. Signs of this influx are evident, particularly in Mount Vernon, where taquerías, tortillerías, boot shops, and botánicas punctuate the storefronts around town.

Though Santos is thankful for the new opportunities, life in Washington has not been easy. He gave up berry-picking a couple years ago, and today works on call, digging clams for a local company. When the tide goes out, he’s summoned in — taking a boat from the nearby town of Stanwood to various islands scattered around the Salish Sea. When he and his co-workers arrive, they throw on heavy waders and follow the receding tide, plunging shovels and rakes into the dark seabed. On a good day he plucks between 600 and 700 pounds of clams from the muddy tidal flats — a haul that will earn him over $100. Most days, however, he brings in between $70 and $80.

Though the amount fluctuates, he earns a paycheck year-round. It’s enough to support his wife and two children. There’s even some left over to send home every month to his mother and father — both subsistence farmers in Oaxaca. He tells me his dream is to eventually bring his parents, now in their mid-50s, to Washington. Though the evergreen-studded peaks are a sharp contrast to the tropical forests of Oaxaca, he thinks they would be at home here — especially given the many other Mixteco farmworkers who have migrated to the area in recent years.

“I like Washington when it’s cold,” says Jesús González, who fled California in 2012 because of the drought. Of Mixteco descent, González is small and sturdily built, with dark skin and high cheekbones. He came to the U.S. from Oaxaca in 1974. For decades, he made a seasonal loop between the citrus groves of Madera, California, north of Fresno, and the fruit orchards and berry fields of Oregon and Washington. In California, González says, he lived in cramped conditions, sleeping with 14 other people on the floor of a small house with a single bathroom and a tiny kitchen. González says there were many factors that made life in California difficult — hard-to-meet harvest quotas, poor housing, bad water, and a general lack of respect. He’d learned to cope with all of that.

But the drought changed everything. The relentless heat, González says, weighed down on the workers like a heavy blanket, and the prolonged lack of precipitation forced farms to fallow land or shut down entirely. Jobs evaporated. By 2012, González says, staying in California was no longer an option, so he packed his belongings and headed for Skagit County. He estimates that between 50 and 100 of his co-workers did the same — moving to the farming regions of Washington and Oregon. “We like to work in the fields — that’s our job,” González says. “But we can only take so much.”

“These workers talk about climate change in a completely different way than Al Gore would,” Franks says. “They talk about fainting in the fields, or crops that wouldn’t grow. They talk about how it affects their ability to make a living. They see climate change from ground level.” To these workers, climate change is not merely an abstraction; it is a sweltering reality that they must confront every day.

Are drought-fleeing farmworkers like Santos and González outliers, or the leading edge of much larger climate migrations to come? One report, published last year by the Climate Impacts Group, suggests the former. The study — which evaluated a selection of journal articles and news stories — found that economics, rather than climate, is the primary factor that would drive a mass migration to the region. “We are a wealthy country, we’re a large country, and we have stable political institutions that, to date, have shown the capacity to come together and work on solutions toward these kinds of problems,” says the center’s Lara Whitely Binder.

Those who do come to the Northwest will be faced with an unpleasant reality, she adds, reciting a list of problems expected to strike the region before the turn of the century: regional temperature increases between 5.5 and 9.1 degrees Fahrenheit; drier summers making the Northwest’s forests more susceptible to fire; declining snowpack, as more precipitation falls as rain instead of snow at higher elevations, straining regional water supplies and increasing the risk of flooding downstream. Along Puget Sound, rising seas could threaten urban infrastructure. “There is a notion out there that climate change is not going to really be that big of a deal in the Pacific Northwest,” she says, “which of course is not true.”

Farther north, in British Columbia, Giles Slade maintains that environmental and economic collapse are part of the same phenomenon. “The social issues tend to blind us to what the ecological issues are,” he says. “But the ecological issues are right down there at bedrock.”

He says there will be a point — even in wealthy and politically stable countries such as the U.S. and Canada — where the costs of climate change become so large that staying put is no longer an option. “People will leave rather than spend all that money,” he says, referring to the kinds of extreme climate interventions, such as geoengineering, that are now being considered. The idea of heading north in response to crisis also has a pedigree in the U.S., Slade says, pointing to the thousands of Americans who fled to Canada in the 1960s and ’70s to escape the Vietnam draft.

By the banks of the Fraser River, he produces a floodplain map of Richmond, and another map showing huge swaths of the city, particularly in low-lying areas along the region’s vast delta, inundated by projected sea level rise. By most accounts, Canada will be beset with many of the same problems facing the northwestern U.S., including megafires, pest outbreaks, melting permafrost, and coastal flooding. “The Northwest might be a staging area,” he says, “but eventually climate migrations will take us farther north than the 49th parallel.”

But how many of us, and where will we all go? And what of the billions of impoverished people around the globe for whom mass retreat is simply not an option? Slade shakes his head as the gray waters of the Fraser roll slowly by. The answers to those questions, he says, are likely not ones we’d want to hear. For his part, Slade has a climate change stronghold in mind, though he asked me not to disclose it. (Suffice it to say that it is well north of any of the destinations discussed in this article.)

“There’s this sense that we North Americans are immune — and for the most part we have been,” he says. “But our immunity is evaporating.” In the developed world, as climate change bears down on us faster and with greater intensity, our ability to adapt will be challenged as never before, he says. There will be more Sandys and Katrinas, more extreme droughts and floods. “It’s all coming,” Slade says. “We’d better be prepared.”