A new report offers a roadmap to building a high-quality early childhood education system.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: Tim Boyle/Getty Images)

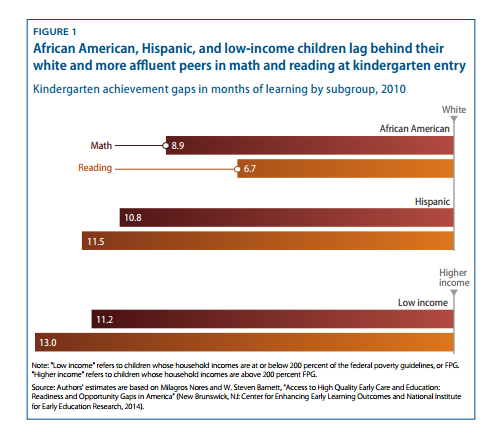

By the time a low-income child enters kindergarten in America, they’re already woefully lagging their more advantaged peers — 11 months behind in math and 13 months behind in reading, according to a recent report from the Center for American Progress.

(Chart: Center for American Progress)

The figure at left, from the CAP report—“How Much Can High-Quality Universal Pre-K Reduce Achievement Gaps?”—illustrates the gulf between both low- and high-income children and minority and white children.

And those gaps only get wider as the years go on—to increasingly more significant effect. As James Heckman, a Nobel Prize-winning economist who has spent decades studying the effects of early childhood education, told the New York Times:

The road to college attainment, higher wages and social mobility in the United States starts at birth. The greatest barrier to college education is not high tuitions or the risk of student debt; it’s in the skills children have when they first enter kindergarten.

But early childhood education has the potential to change all of that. The CAP report estimates that a high-quality, universal pre-K program would essentially close the reading achievement gap and dramatically reduce the math achievement gap (by 48 percent for black children and 78 percent for Hispanic kids). And politicians across the spectrum have hopped on the early education bandwagon. The Obama administration has repeatedly called for a universal pre-K program and has directed significant funding to early childhood education. Hillary Clinton, a long-time champion, has also advocated universal pre-K as part of her ambitious childcare platform. Though Donald Trump has so far remained silent on the topic, a number of Republican politicians have embraced the pre-K cause.

There is, however, one enormous catch: It’s hard to build a high-quality early childhood education system, and quality matters. The CAP report estimates that only one-third of four-year-olds enrolled in a center-based program were in a high-quality classroom. Among four-year-olds enrolled in full-day programs, only 10 percent were in high-quality classrooms.

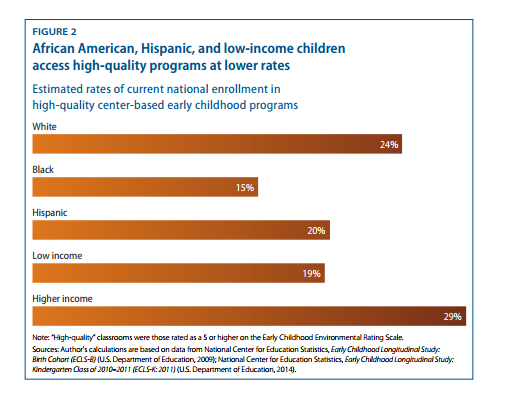

(Chart: Center for American Progress)

Not surprisingly, minority and low-income children were much less likely to be in high-quality programs, as the figure at left demonstrates.

There could, however, be some solutions. A new report from the Learning Policy Institute, a non-profit, non-partisan research organization, breaks down the experiences of four states—Michigan, West Virginia, Washington, and North Carolina — that have successfully built high-quality early childhood education systems. Each state, which feature different demographics and faced different challenges, took varying paths toward leveling the ECE playing field.

The ECE programs in both Washington and Michigan, for example, began back in 1985; West Virginia’s program wasn’t launched until 2002. Washington’s program, an expensive but effective “wrap-around” model, is relatively small (serving only 17 percent of the state’s four-year-olds) and targeted at the poorest of the poor, while West Virginia’s program enrolled 75 percent of the state’s four-year-olds in the 2014–15 school year..

Despite these differences, the four states profiled had five things in common:

A Focus on Quality and Improvement

All of the states in the report took the time to develop both clear, comprehensive standards and systems for evaluating programs and guiding improvement — and then linked funding to those standards. At the same time, all four states gave counties and programs the freedom to adapt to the local environment and local needs.

On the surface, this seems kind of obvious: Of course, there should be clear standards for early childhood education, just as there are for public K-12 schools. But one of the main challenges ECE has faced has been the lack of such standards. When ECE is provided by a jumble of different places — the local public school, a daycare center, the nearby church, etc. — it’s hard to institute a set of uniform standards.

Investments in Training and Coaching

Childcare workers (which many ECE providers are classified as) are currently some of the lowest-paid professionals in our economy, and many have no actual training in their field. The four states profiled sought to change that — they all require lead teachers to have a degree in ECE, child development, or a related field. The standards were phased in, giving teachers several years to obtain the necessary credentials, and states worked with local community colleges, technical colleges, or county education offices to make sure that providers had access to the necessary courses. States also provided financial assistance to teachers as they obtained their credentials, as well as to teachers who sought additional training. West Virginia, for example, developed an apprenticeship program — a four-semester program that allowed teachers to remain in their positions while taking classes. Some states got creative with salaries as well, supplementing providers’ salaries so they weren’t tempted to take their newly earned credentials to the (better-paying) local public school system.

Integration of ECE With K-12 Schools

All four states in the report worked to integrate their ECE programs with the public K-12 schools to ensure that students were ready to transition. They integrated data systems and thought carefully about bureaucratic structure, placing ECE agencies within the Department of Education or the Department of Health and Human Services, for example, to ensure cooperation.

Finding the Funding

All the states profiled relied primarily on state funding dollars for their programs, but they also strategically utilized federal funding streams — everything from Head Start funding to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families to Title I funding — to maximize the available resources. In a particularly creative arrangement, providers in Michigan operate “blended classrooms” that combine a part-day state-funded slot with a part-day Head Start (federally funded) slot. Other states pieced together private funding, foundation funding, and federal grants.

Finding Some High-Profile Supporters

In each of the four states in the report, a political champion led the charge for high-quality ECE. In Washington, Michigan, and North Carolina, it was a committed governor pushing the program forward and fighting for funding. In West Virginia, several senators advocated heavily for the state’s ECE program. But the states also created broad public-private coalitions of advocates — business and religious leaders, police officers, philanthropists, and the like. Interestingly, all four states integrated private providers (including religious providers) into the programs, which both ensured the support of those providers and gave parents more program choice.

As I wrote last week, investing in children pays off in the long run, many times over, and a major investment in ECE in this country is long overdue. But any such investment must include an emphasis on quality. The experiences of Washington, Michigan, and North Carolina suggest that a high-grade early childhood education system is not out of our reach.

||