To state the obvious: Americans are worried about the economy.

Pundits continue to debate how much of Donald Trump’s victory last month was attributable to the economy and how much was attributable to uglier factors like racism, sexism, or nationalism, but there’s no denying the fact that quite a few Americans feel like something is broken in the modern economy.

A new paper from the Equality of Opportunity Project, led by economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, sheds some light on why so many people feel something is amiss. The paper documents a dispiriting trend: Unlike past generations, today’s young adults just aren’t doing as well as their parents.

To find out more, we talked to Robert Manduca, one of the paper’s co-authors.

What was the question that you guys were trying to answer with this paper?

We were interested in trying to measure the extent to which kids grow up to earn more money than their parents, and how that’s changed over time. It’s [a question] people often talk about when they think about “What is the American Dream?” — this idea that if you have kids and they play by the rules, they should go on to have a better standard of living than their parents.

And what did you find?

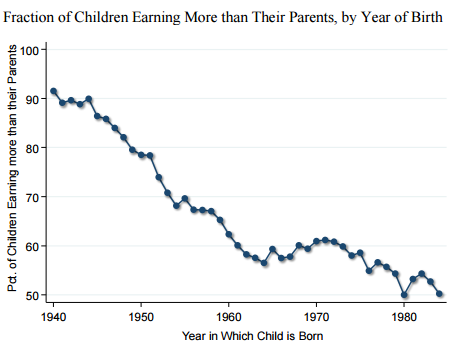

Basically, for children born during the mid-20th century—so for people who were born during the 1940s and ’50s—we measured their incomes at age 30, so those people were 30 starting around 1970 or so. Those generations of kids experienced very high, widespread rates of upward mobility. Something like 90 percent of the kids born in 1940 grew up to earn more than their parents did, after you adjust for inflation.

However, since then there’s been quite a dramatic decline. Of kids who are around 30 years old in 2010–14, only about half of them grow up to earn more than their parents did at age 30.

[Editor’s Note: The graph above, from the Equality of Opportunity Project, illustrates the trend.]

And what happens if you look at a different age? Because you could imagine that maybe 30 is not what it used to be.

Yeah, exactly. One of the things we wondered was … because young adults these days are sometimes going to school for longer, or taking more time to embark on their careers, you could imagine that would mean that 30-year-olds today are earlier in their labor market trajectories than 30-year-olds were in mid-century.

So we did the same analysis comparing kids at age 40 to their parents at age 40, and we found broadly similar results.

So it’s not just that everyone’s living in their parents’ basements for a little bit longer today?

Right, unless they’re staying there until age 40.

(Photo: Harvard University)

And who is this affecting, in terms of the income distribution? Is it poor people, middle-income people, higher-income people?

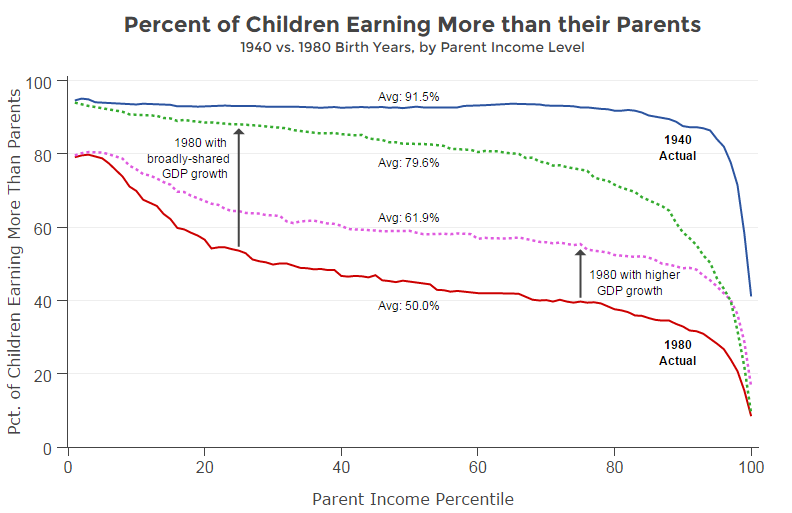

The decline has been pretty widespread across the board. It’s concentrated in the middle. Even today, people who grow up at the very bottom of the income distribution still have a relatively higher chance of beating their parents just because there’s so much room for them to move up.

And then, conversely, the absolute mobility, even in the earlier periods, was lower for people at the very top of the income distribution for the same reason — if you start at the very top, you basically have to stay there to beat your parents.

But throughout the middle, that’s where the decline has been concentrated.

[Editor’s Note: The graph above illustrates how absolute mobility has changed across the income distribution.]

And what parts of the country experience this trend most acutely?

Several states in the industrial Midwest saw a very large decline, though also some states in the West, like Nevada, Washington, Alaska, and Hawaii.

You guy also looked at two big drivers of this trend — lower gross domestic product growth and inequality.

We know that there have been these two big changes to the economy since the mid-20th century. One is that the rate of economic growth has slowed somewhat, and then also there’s been this marked increase in inequality.

We wanted to try to gauge the relative importance of the two trends. So we did these counterfactual simulations where we asked, if the income distribution had changed like it did, but overall total growth had stayed at the high rate of the mid-20th century, what would absolute mobility have been like?

And, conversely, if growth had slowed like it actually did, but the income distribution had stayed similar, what would absolute mobility look like?

What we find is that increasing growth while maintaining the current unequal income distribution would increase absolute mobility somewhat. It would close about a third of this decline, if that had happened.

But the increase in inequality accounts for a much larger proportion of this decline — about 70 percent. What’s important for absolute mobility is to have income growth across all levels of the income distribution. Certainly, more growth helps but what’s really important is that that growth happen at all income levels and not be concentrated into a very small part of the distribution.

The obvious implication of this research is that the argument that all we need to do to address this is to get the economy growing again is somewhat flawed. That isn’t, on its own, going to be enough?

What needs to happen is to have growth that is spread across the income distribution. So if the economy really sped up but all of that growth went to the very top but wasn’t widespread, that wouldn’t have much of an impact on the absolute mobility statistics.

Do you have any thoughts on policy actions that would ensure broad-based economic growth, as opposed to just continuing on our current path?

There are lots of policies that people talk about as ways to reduce inequality or promote economic growth or wage growth. I think it would probably take a fairly wide range of policies. I don’t think that there’s necessarily one silver bullet.

But the key, I think, will be to maintain the focus on the question of “Is this increasing incomes across the distribution?”—and to make that the standard by which we’re looking at the economic effects of policies.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.