Ahead of the Environmental Protection Agency’s annual accounting of its policing of environmental violations over the past year, an advocacy group has crunched the numbers and found them lacking.

The EPA is in charge of ensuring companies and utilities follow national environmental laws. Its enforcement has actually been on the decline for the past decade and reached 10-year lows in the fiscal year 2017, according to the agency’s own data. But the numbers really plummeted between the fiscal years 2017 and 2018, according to the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative, an advocacy group formed by university researchers to counter what they see as the Trump administration’s rejection of science.

The declines are the result of a deliberate turning away from upholding the law, the EDGI argues. The group concludes that from interviews that volunteers conducted, with 21 current and recently retired EPA employees, as well as documents the group obtained.

“The administration has strongly sent a message, to the folks who do enforcement, that they should cut back on their role,” says Marianne Sullivan, a public-health professor at William Paterson University in New Jersey and an EDGI volunteer who conducted the interviews. “There are declining resources. There’s much more deference to industry.”

“What it adds up to is large decreases in enforcement across these really important programs that protect the health of all Americans,” Sullivan adds.

An EPA spokesperson did not respond to detailed questions by press time.

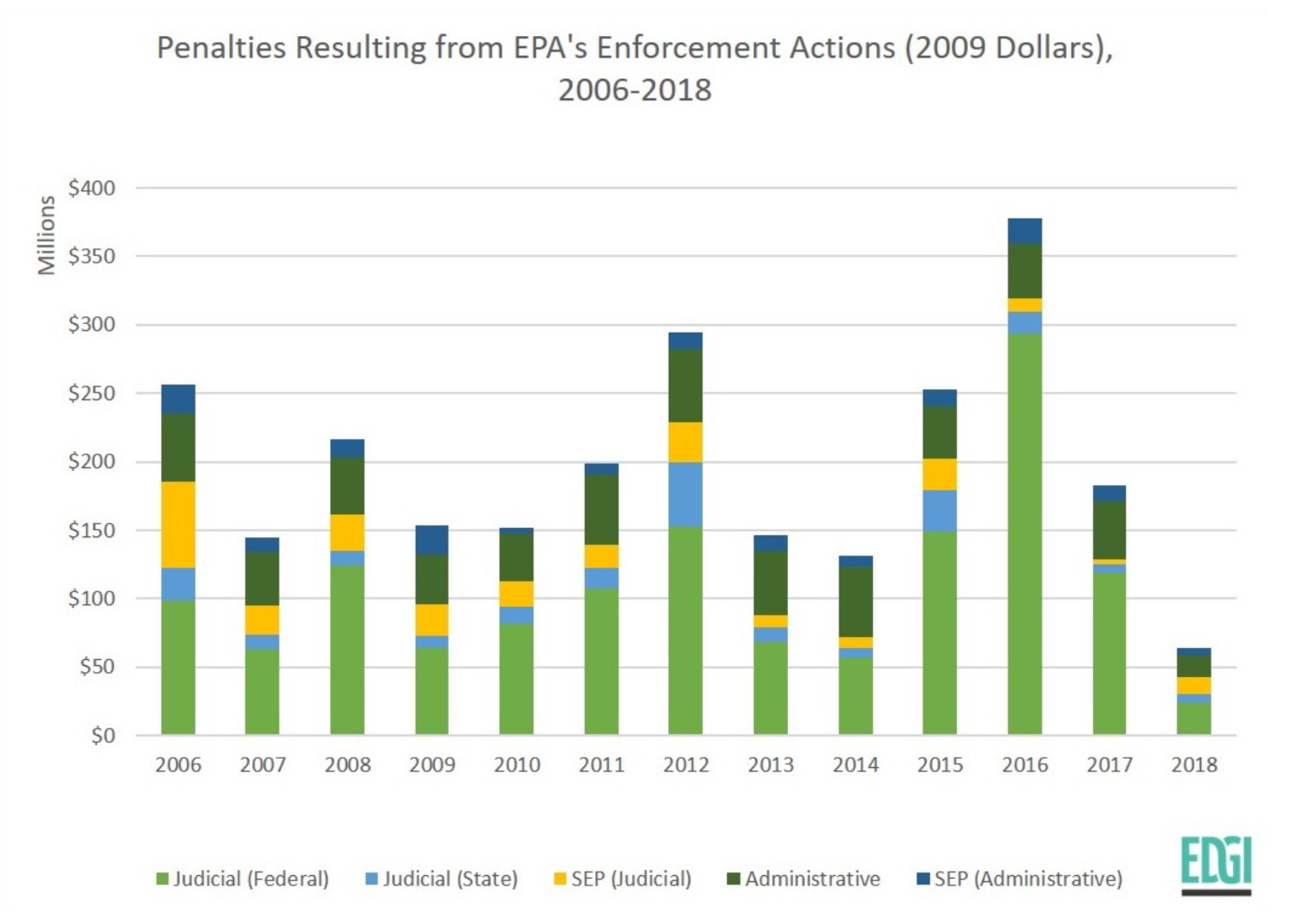

Leif Fredrickson, another EDGI volunteer, ran the numbers using publicly available EPA data. Among the results he found: The amount of money companies had to pay in fines and clean-up projects in 2018 is paltry compared to the amount they’ve shelled out in the past dozen years.

(Source: Environmental Data and Governance Initiative)

Polluting entities settled 54 criminal cases with the EPA in 2018, compared to 87 in 2017, 81 in 2016, and more than 100 every year between 2010 and 2015.

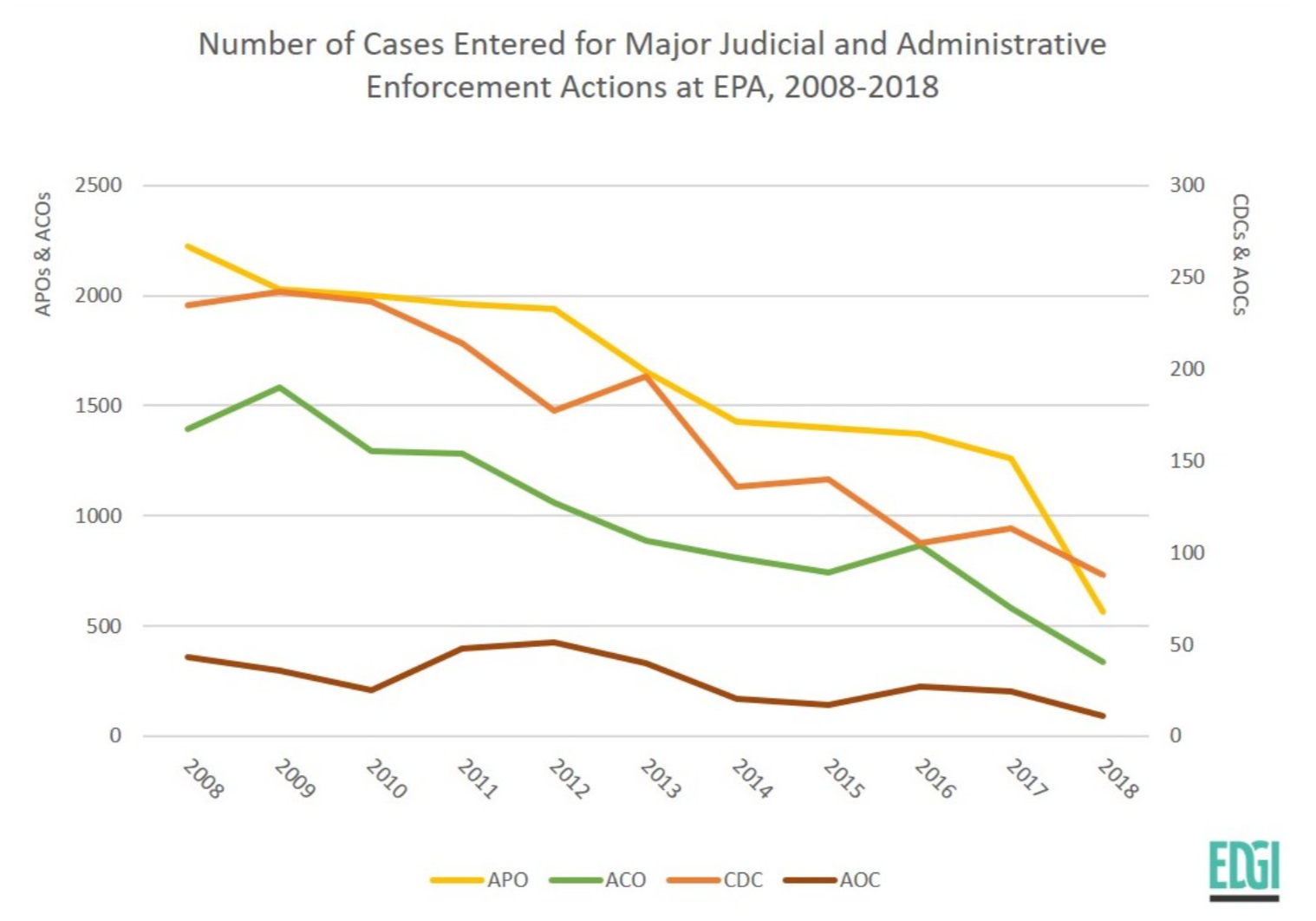

Finally, several kinds of non-criminal enforcement actions the EPA can take declined as well, a couple of them especially steeply in the last year:

(Source: Environmental Data and Governance Initiative)

There are dozens of ways to track the question of “How much policing is the EPA doing of environmental violations?” But nearly everything Fredrickson looked at showed shrinkages. “Virtually everywhere,” he says.

The EPA hasn’t yet published 2018’s enforcement data, and these numbers aren’t final. The agency typically fixes this data, for example correcting dates and removing duplicates, after the end of the government’s fiscal year on September 30th, Fredrickson says. Then it publishes the data, sometime in the winter. Still, based on past correlations between the EPA’s preliminary and final enforcement data, Fredrickson expects the fast-decline trends to remain the same.

What accounts for the drop in EPA muscle?

When EPA numbers last year showed a decline in enforcement, agency officials reiterated their commitment to environmental law. “A strong enforcement program is essential to achieving positive health and environmental outcomes,” Susan Bodine, head of the EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, said in a statement. To NBC News, spokesperson Liz Bowman said, “EPA is focusing on finding efficient ways to deter noncompliance and return facilities to compliance with the law.”

But Sullivan and Fredrickson argue that their evidence suggests some in the agency are deliberately trying to ratchet down its environmental policing. The Environmental Data and Governance Initiative obtained an internal memo, from the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, called “Possible Reasons for Decline in Inspection/Enforcement and Ideas for Reversing.” (Citing the need to protect sources, EDGI did not share the memo with me, though it’s quoted in a public report on EDGI’s website. The EPA didn’t answer questions sent about the memo.)

One possible reason the document cited was a “consistent message” from the Trump administration was that it wanted “to slow enforcement.” Political appointees to the agency passed along complaints from regulated entities and asked questions of EPA enforcers that made it seem as if the “EPA was at fault.”

“What you have now is there are explicit directions not to do certain types of inspections and numbers overall are dropping,” one staffer interviewed by Sullivan and her colleagues said.

However, other causes of declining enforcement did not have to do with specific agency goals, the memo argues. For example, the EPA made it one of its goals to defer more often to the states. Some employees “incorrectly interpreted” this guidance to mean they “should do no inspections and enforcement in authorized states,” according to the memo. In addition, companies seem emboldened by the Trump administration’s friendliness to industry. They now push back more on EPA demands, which slows settlements.

One interviewee, who inspects rental homes for lead paint, told EDGI volunteers that landlords used to agree to meetings, or, at worst, delay them. Now, landlords “hang up, or they’d start screaming at me.”

Fredrickson, Sullivan, and others in the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative want to see the EPA enforce the rules more robustly. They don’t want so much policing left to the states. Many states are ineffective without a strong EPA, they argue. As an example, the EDGI report points to Oklahoma, home of Scott Pruitt, who was the head of the EPA from February of 2017 until July of 2018. Oklahoma’s Department of Environmental Quality roughly halved the number of formal air enforcement actions it took, and the fines it collected, between 2016 and 2017.

The worry is that less enforcement means more Americans may be exposed to lead, smoke, and other pollutants that the EPA regulates. That may lead to long-lasting diseases. This is what drives Sullivan’s advocacy, she says: “At the end of the day, these are really issues of public health. Issues of environmental regulation come back to public health.”