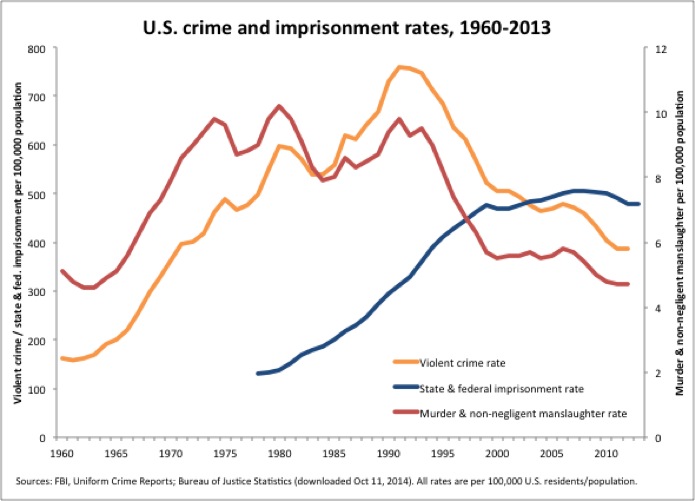

We do a lot of punishing in America these days—more than virtually every other country, and far more than we did when crime rates were higher.

This punishment is not, as President Lincoln might have put it, distributed generally over the Union, but rather concentrated on poorblack and Latino neighborhoods.

It costs a lot of money, in addition to its social and (many believe) moral costs. It doesn’t seem to make us safer.

This system of punishment has also been centralized and bureaucratized, in ways that often make the system’s promise of “correction” or “rehabilitation” hard to take seriously. As the late Harvard law professor William Stuntz observed, incarceration levels exploded in the late 20th century amidst a push for more prosecutorial efficiency: “A locally run justice system grew less localized, more centralized.”

In recent years, a nascent recognition has begun to take root on both sides of the political aisle that our current incarceration system is not only too harsh and too expensive, but an assault on the dignity of the people pulled into it. (Among theorists and activists, these critiques go back a lot farther.) As we think about reforms, we should note the successes of a still-exotic creature in that system: the community court.

YOU DON’T SEE A lot of smiles in American courtrooms these days. But at the Red Hook Community Justice Center in Brooklyn, court officers smile at defendants, prosecutors smile at defense lawyers, and defendants rarely seem to leave the courtroom without smiling at the Justice Center’s presiding judge, Alex Calabrese.

Take Ms. Hughes (whose name has been changed to protect her privacy), who looks especially unhappy when her case is called. Like many defendants, Calabrese notes, she’s a “persistent misdemeanant”—a ton of small offenses, constantly in and out of jail. Calabrese weighs the details of her drug-possession case for a few minutes and offers her a choice: a year in jail or six months in drug treatment, with charges dismissed if she’s successful. Through her legal-aid lawyer, Hughes warily agrees to option two.

The Justice Center cut recidivism by 10 percent over two years relative to traditional criminal courts, and also sent 35 percent fewer offenders to jail, using alternatives like drug treatment and trauma counseling the vast majority of the time.

Calabrese asks her to approach the bench, which, unlike most, is placed at eye level so that he’s close to defendants and can talk with them from a position of equality. (Julian Adler, the Center’s director, notes that “Downtown the bench is high, it’s Kafkaesque, everything’s through a microphone, the wood paneling is dark and intimidating.”)

Calabrese is looking through the details of Hughes’ arrest. When he reads the address where the police picked her up, Hughes looks agitated. “Wait a minute,” the judge says. He’s realized that the address on the booking report—an area mall—is off by a few blocks. It doesn’t make a difference in the case, but Hughes smiles the instant he acknowledges the error.

They start talking about Hughes’ life; it turns out she has an eight-year-old daughter. “Wouldn’t that be a great reason to get clean?” Calabrese asks. Hughes nods. “We’re 100% behind you,” Calabrese declares. By the time Calabrese is ready to move on, Hughes looks optimistic. “You’re going to make my day tomorrow when you show up!” Calabrese calls out as she waves goodbye.

As the prosecution and defense are preparing for the next case, Calabrese reflects on Hughes and her lengthy list of priors. It’s a typical example, he asserts, of how most courts process low-level issues involving addiction or mental health problems. “You go in with the issues, you come out with the issues,” he says. “No one’s addressing the underlying problems—it’s not a problem-solving approach in the traditional court system.”

“You’ve got drug addicts going in, drug addicts coming out,” Calabrese sighs. “Like they say: ‘Life in prison, 30 days at a time.’”

Later, in the Justice Center’s upstairs offices, Calabrese discusses punishment in America:

Fifteen years ago, it was “tough on crime,” “lock ‘em up.” But “lock ‘em up” just doesn’t make any sense. …

The social workers will say, “Well, when they get out of jail, where are they going? Are they going back to the same neighborhood?”

“Yeah.”

“Are they gonna be working?”

“Well, no, they’ve just been in jail.”

“Are the drug dealers still there?”

“Yeah.”

“Social workers will tell you,” Calabrese concludes, “over 90 percent go right back to heroin, or crack, or whatever it is. So it was a foolish system…. It simply doesn’t work, and it costs a fortune. And people realize it costs a fortune now. So there’s just a better way to approach it.”

WHAT IS THE JUSTICE Center’s “better way”?

It’s a community court—one of about 70 worldwide—which means that it’s closely entwined with the neighborhood surrounding it. It handles the kinds of misdemeanors and low-level felonies—everything from drug possession to grand larceny—that account for roughly 80 percent of state court cases in America.

It’s also multi-jurisdictional—the first in the country—which means that its sole judge, Calabrese, doesn’t just hear criminal cases, but also landlord/tenant disputes and certain types of family-law cases that the community wants help with.

It’s more than a courtroom: the building’s second and third floors house social workers and staffers who oversee a variety of community programs, including a housing resource center, a Navajo peacemaking program, a G.E.D. program, and a youth court, which empanels “juries” of teenagers from the community to discuss and resolve infractions with their peer “defendants.” The community programs, financed and run as a public-private partnership, underscore an approach that seeks “alternatives to incarceration”—ways for defendants to make amends and address their problems that stand between the binary options of “jail or nothing.”

A community mural in the Justice Center’s break room. (Photo: Red Hook Community Justice Center)

And it carries out these mandates with a combination of what social workers call a “strengths-based approach” and what legal scholars like Yale Law professor Tom Tyler have termed “procedural justice.” Both are deceptively simple. The former says that we should address ourselves to the good things people have going for them—their abilities and resources—not their defects and disorders. The latter is even more intuitive: People are more likely to trust and cooperate with an institution if they feel they’ve been treated fairly by it, as Adam Mansky, director of operations for the Center for Court Innovation (the non-profit that created the Justice Center) puts it.

This doesn’t just sound nice in theory; it also works.

In 2013, the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) released a comprehensive, federally funded study of the Justice Center. NCSC found that the Justice Center cut recidivism by 10 percent over two years relative to traditional criminal courts, and also sent 35 percent fewer offenders to jail, using alternatives like drug treatment and trauma counseling the vast majority of the time. Altogether, the authors calculated, the Center’s efforts yielded $15 million in savings, exceeding the Justice Center’s costs by a factor of nearly two-to-one.

Young offenders are often diverted from criminal justice into “restorative justice” projects—appropriate community service that makes restitution to the community.

“It was a fairly conservative cost-benefit analysis—they didn’t compare Red Hook [in the ’80s] to Red Hook today,” observes Adler, referencing the neighborhood’s chaotic past. (A July 1988 LIFE Magazine spread is headlined only by the word “CRACK” in enormous font; the article notes that even ice cream trucks were selling the drug at the time.) The NCSC study notes that crime in the Justice Center’s jurisdiction, “in marked contrast to arrest levels in adjacent police precincts,” fell “sharply upon the opening of the Justice Center and has remained relatively stable since that time,” even as the neighborhood remains poor. (Half of Red Hook lives in the Red Hook Houses, whose nearly 3,000 units comprise the second-largest development in the city.) Among the Justice Center’s fans is New York Police Department Commissioner Bill Bratton, who attests that its “inclusive approach … has succeeded in reducing fear and disorder and in making southwest Brooklyn far safer.”

The Justice Center is not for rarer and more serious crimes like rape and murder, but its approach should not be mistaken for coddling those who commit lesser ones. The NCSC study found that the defendants who don’t comply with their initial treatment plans end up receiving longer jail sentences at the Justice Center than they would have downtown. But trying treatment first acknowledges a vital truth: Most offenders were victims first.

“If you’re knocking people over the head to get the heroin, you’re probably staying in jail!” Calabrese exclaims. “But that’s not what usually happens. Usually, if they’re committing crimes, they’re committing petty crimes to support themselves—crimes where even the victims, when the prosecutor says, ‘This person’s going to treatment,’ most of the victims are happy with that result. They say, ‘I’m glad that he or she is getting the help they need.’” And that dignified treatment can be the first step toward transformation: Calabrese speaks proudly of former homeless or drug-addicted defendants who have gone on to earn medals as soldiers, pursue master’s degrees, or simply achieve meaningful full-time employment with stable family lives.

The NCSC study authors note that it’s hard to draw a strict causation line from the center’s approach to its results. But based on their research, the authors concluded that “the most plausible explanation” is the Justice Center’s rare, dignity-centered approach. “All aspects of court operations,” they wrote, “as well as the courthouse itself, were designed to preserve individual dignity and support perceptions of procedural fairness in the court process as a whole.”

“FROM ITS FOUNDING,” JUSTICE William Brennan wrote in a famous Supreme Court opinion, “the Nation’s basic commitment has been to foster the dignity and well-being of all persons within its borders.”

How does the Justice Center foster the experience of dignity on the people who enter its doors?

First, there’s the building’s physical design—the bench at eye level, the rooms bathed in natural light. The holding cells have thick glass—not bars—and they, too, feature natural light, as well as private bathroom partitions. Most other jails, Adler and Calabrese note, offer a “hole in the floor” at best. The clinics and hallways are spacious and inviting; the walls are lined with photos of the neighborhood taken by local youths. “All are attempts,” Adler explains, “to infuse this place with some sense of humanity and dignity.”

Second, the Justice Center’s staff and officers build friendly and often deep ties with Red Hook. “When offenders were asked to describe in their own words how their experiences at the Justice Center differed from their experiences in other courts,” according to the NCSC study, “the word they most frequently chose was “respectful.’” One former defendant said that the “court officers are a lot different from downtown,” noting even that “they see me on the bus and come sit by me and ask me about my son. So, I catch up with them on the bus and they’re very courteous.” As Mansky points out, this cycle can be virtuous: “It’s not uncommon for defendants afterwards to thank the police and court officers for how they’ve been treated. And I’ve had court officers say, ‘I don’t know why people coming through here are so nice and friendly!’”

Sabrina Carter, who grew up in Red Hook and now runs the Justice Center’s youth court, attributes the community’s trust for the Center to these small gestures, like the fact that the court officers say good morning to everyone who comes in. Others cite similar signals like the willingness of Calabrese, who commutes to work each day by motorcycle, to leave his bench to investigate the habitability of New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) apartments himself. “He hasn’t done it that often,” Mansky explains, “but everyone in the Red Hook Houses … knows of him as the judge who goes into the Red Hook Houses.”

Third, the Justice Center strives to include everybody. Its offerings range from Carter’s youth court and the housing resource center to art programs, training for young people in community organizing and advocacy, and internships. “People are more inclined to come here,” Carter suggests, “because they’re not always necessarily coming here for a court date … you can’t walk into 120 [Schermerhorn Street, Brooklyn’s main criminal court] and say, ‘I’m looking for a youth program for my teenager, he likes photography,’ and they can’t say, ‘Oh, we have a person downstairs who runs a program like that.’ But we do, so it brings court and community together.”

Fourth, the Justice Center stresses that everyone in the community has something to offer in return. Young offenders are often diverted from criminal justice into “restorative justice” projects—appropriate community service that makes restitution to the community. A teenager picked up on graffiti charges, for example, might be enlisted create a mural—one such mural, in the Justice Center’s break room, locates the court at the intersection of “2nd Chance St.” and “Perseverance Road.”

Citizens of the neighborhood are likewise invited to have a say. Through advisory boards, community meetings, and regular surveys and focus groups, staff and the community regularly consult on how to run the Justice Center—a dialogue, Mansky notes, that led to the court’s multi-jurisdictional designation and its inclusive offerings. (“People would say to us, ‘That’s great that you’re going to offer all these services … but are those programs limited just to the community’s bad guys? What if I have a problem, or what if my sister is a victim of domestic violence, or I have a son who needs something to do after school?’”) The partnership precedes the physical center: When Mansky and his team were evaluating locations back in the late ’90s, they chartered a bus and invited community residents to join them on a tour of prospective sites. The former parochial school where the center now sits “was the place they chose unanimously,” Mansky recalls. “It was different from the place that we originally thought would be the best one.”

The Center’s efforts yielded $15 million in savings, exceeding the Justice Center’s costs by a factor of nearly two-to-one.

Finally, the Justice Center lets each person steer—as much as possible—his own course. Especially in its non-court programming, the Justice Center relies heavily on the individual responsibility of each participant. The youth court’s sanctions—determined by community youth—are voluntary, but their compliance rate is nearly 90 percent. Similarly, the Center’s Navajo peacemaking program trains community members to resolve neighborhood conflicts themselves.

As disciplinary body, the Justice Center can’t provide quite as much latitude—people are not allowed to opt out. But it goes out of its way to treat each defendant as an individual with desires and responsibility for her future.

“Every single time that I sat in front of Judge Calabrese, he would always ask me, ‘What do you think is best for you?’ And every time I suggested something, that’s where I went,” recalls Ieysha Torres, a woman now in her twenties who wound up at the Justice Center on a marijuana charge as a 13-year-old and has come to see the staff as her second family. (As captured in the 2000 documentary Nuyorican Dream, Torres’ original family life was extremely chaotic; the film tracks her mother’s descent into a fatal heroin addiction, as well as her other relatives’ struggles with poverty, jail, and addiction.)

Torres recalls, by contrast, a hearing downtown in which she asked if her case could be sealed so that it wouldn’t interfere with her college applications. “The judge flat out said to me, ‘You’re lying—everybody uses that excuse,’” she remembers. Torres was stunned. “With Calabrese,” she says, “I can talk to him. He asks me questions, I answer back—it’s a conversation…. My side is heard. He speaks. We come to an agreement.”

Strikingly, this individualized approach often leads to defenders choosing to pay a higher price for their crimes—but a price with meaning. As Calabrese points out:

It’s actually harder to go to treatment for a lot of people than it is to go to jail for 15 days. [One defendant] said, “You know, I guess I could have done my jail time and gotten this case over quick.”

And the answer was: “Yes!”

“But,” he said, “I’m happy I did this, because I feel so much better now.”

And what did he steal? He stole some Red Bull or something—Five Hour Energy or something like that. How much jail time would you get for that? Not much! But he wanted to do treatment.

“It’s really about getting the message across: we’re here to support you, we want you to be successful,” Calabrese says. “We expect you to do what you need to do, but we’re behind you. We’re not looking for ways to trip you up and send you to jail.”

Torres, whose case has now been over for four years, chokes up when she reflects on the benefits of this approach. She works full time, got her G.E.D. at the Justice Center last year, and is working on going to college. “They treat you like a human being,” she says. “They treat you like they know that you’re going through something, like you’re more than just a person standing in front of them because you did something.”

“I never thought I was going to graduate,” Torres continues. “I’d had so many difficulties staying positive or not giving up on myself or feeling like I couldn’t make it, just because a lot of people told me that before.”

“But you’re smart!” shouts Calabrese, who has just leaned into the room.

“He always tells me that,” Torres says, through tears.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN for the rest of the American justice system? Community courts like the Justice Center have been slowly gathering steam since the 1990s, but they still operate, as one scholar put it, “on the fringe of the criminal justice system” (the 2013 NCSC study noted 33 in America). We ought to help accelerate their spread.

The Center for Court Innovation has been a principal agent of the model’s spread thus far. In addition to running about 20 existing “demonstration projects” (mostly around New York), CCI has recently been asked to plan a new center for Brooklyn’s troubled Brownsville neighborhood; another will soon be available to Newark’s entire low-level criminal population, and a peacemaking center will soon launch in Syracuse. And Calabrese notes proudly that they have helped inspire courts as far away as Vancouver and Melbourne. “Sometimes they take pieces of what we do—because we’re like the car with all the deluxe options—but the theory’s the same,” he says. Portland, Oregon, set one shop up in a homeless shelter. “Dallas goes to truck stops where the prostitutes hang out and they have a court there, and the court brings services! It’s … using the power of the court to help them get their lives back on track.” These courts need not be restricted to large urban areas: as Vermont’s experience demonstrates, they can also help reduce recidivism and generate substantial cost-savings in less populated environments.

The Justice Center strives to include everybody. Its offerings range from Carter’s youth court and the housing resource center to art programs, training for young people in community organizing and advocacy, and internships.

Drug courts, close cousins of the community court, are more prominent, and are also worthy investments (there are nearly 3,000 in America today). But they often lack two central features that make community courts, at least in their ideal form, so compelling: a cross-section of services and programs—recognizing the variety of issues that residents of communities racked by drug addiction face—and a commitment to engaging and empowering that community itself.

Beyond expanding the community-court model from curiosity to common practice, we should continue to fine-tune community courts to make sure they live up to these promises. The critiques levied at such courts by mostly admiring scholars suggest that more can be done, especially in engaging communities. Jeffrey Fagan and Victoria Malkin of Columbia University (who studied the Justice Center specifically) have expressed concern that the individuals engaged by such courts are “often not representative of the community,” noting that community leaders and groups consulted by the Justice Center “do not always speak for the majority of Red Hook’s residents” and that “gentrifiers” of Red Hook often take better advantage of opportunities to be heard. Fagan and Malkin don’t believe this critique overpowers the good that the Justice Center does—they conclude that “it produces more than ‘enough justice’ … to affirm its founding principles.”

Progress on this front should not be impossible. Community courts can, for example, make special efforts to hire more people, like Sabrina Carter and several court officers over the years, who grew up in the neighborhood. They can, like the Dallas courts at the truck stop, move operations closer to the issues—imagine housing court on the first floor of large housing project. They might, as Harvard law professor Adriaan Lanni has proposed, convene juries from the neighborhood, using those mechanisms to give a broader array of local residents a say in charging and sentencing suspects for crimes.

These suggestions can help community courts better contribute to transforming a harsh, costly, and undignified system and into a fair, affordable, and dignified one—inverting the trend Stuntz identified by making a centralized system more local.

The individual and collective promise of such a project was on display in Calabrese’s courtroom last June.

Nine months earlier, when Olivia (also not her real name) was arraigned at the Justice Center, she had a terrible heroin problem; in her mug shot, she looks like a corpse. In June, having completed nine months of in-patient treatment, she looks like she could have stepped out of a college brochure.

“The defendant has clearly put an incredible amount of time and effort into this case and into her sobriety,” Calabrese announces to the courtroom. He invites Olivia to approach the bench. “I want to thank you for the chances you gave me,” Olivia says. Without the judge and the court’s support, she swears, she wouldn’t have been able to “come out on the other side.”

Calabrese is not about to get stuck with the credit. “What you accomplished—if I had gone through what you went through, I don’t think I would have been able to do it. It’s something to be proud of, because it’s special,” he insists.

Calabrese asks what she’s doing now, and Olivia tells him that she’s working as an intern at a treatment facility, doing administrative work and hoping to run counseling groups before too long. Calabrese beams: “You could be so effective because you’ve been there and done that!” he exclaims.

Calabrese hands her a certificate recognizing her successful completion of treatment. Olivia weeps as the courtroom applauds. “This case is dismissed. We’re so proud of you,” Calabrese proclaims. “Dismissed and sealed by the people. Excellent work by the people.”