Doctors nationwide have been prescribing fewer opioids—painkillers such as OxyContin, Vicodin, and Percocet—since 2010, according to a new analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Still, prescribing rates remain high compared to the recent past. They also vary widely by county, with rates increasing in about one in four counties nationwide, even while in rest of the country they are falling.

The new numbers offer a cautiously optimistic look at efforts to curb an ongoing health crisis in America. The number of Americans who have died of overdoses on opioids such as prescription painkillers and heroin has grown every year since 2002; in 2015, the latest year for which solid numbers are available, opioid overdoses killed 33,000 people. That’s about the same number of people who die from car accidents and gunshot wounds every year.

Unnecessary, plentiful painkiller prescriptions are thought to be one major driver of the crisis. Between 1999 and 2010, the amount of opioids American doctors prescribed per capita more than quadrupled. Having all those pills in people’s medicine cabinets may make it easier for people to sell their extras, or for teenagers to steal them from parents and grandparents. In addition, among people who take opioids as prescribed, a minority may become addicted over time, and one study found the risk is higher if their scripts last many weeks. For those who are addicted to opioid painkillers, the chemically related heroin may be the next step.

Over the past few years, doctors’ groups, states, and the CDC have tried several strategies to curb prescriptions. All 50 states have created computer systems for tracking narcotic prescriptions, and some have passed laws regulating pain clinics. In 2016, CDC scientists published a research-informed guideline for doctors prescribing opioids to people with chronic pain. It suggested doctors try non-opioid painkillers such as Tylenol, exercise therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy first to treat pain. They also advised doctors to avoid, when possible, giving out opioid prescriptions that are high-dose and last weeks at a time.

To check whether these efforts have made a difference, the CDC scientists behind this latest analysis examined data from retail pharmacies that account for 88 percent of America’s prescriptions. They checked all the opioid prescriptions these pharmacies gave out, excluding those for cold medicines containing opioids and buprenorphine prescribed for opioid addiction, between 2006 and 2015.

They found that, across America, overall opioid prescriptions have fallen every year since 2012. High-dose prescriptions have been falling since 2010. Long-term prescriptions, lasting more than 29 days, increased between 2006 and 2012, but have been stable since.

For health officials, those are wins. “Reducing overprescribing practices prevents people from becoming addicted in the first place, potentially changing the demand for opioids,” three CDC researchers write in an essay, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, about the new agency data.

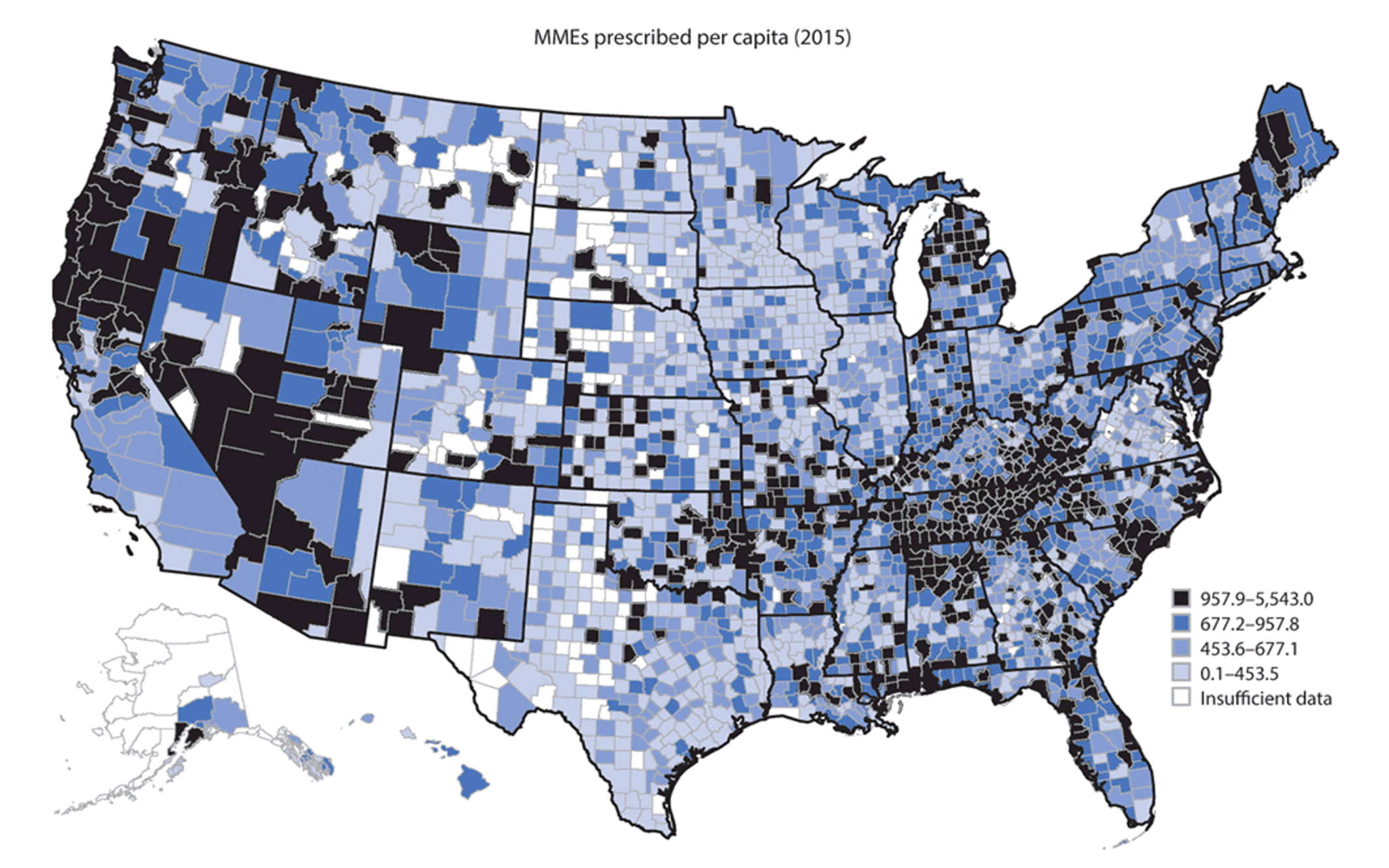

Not all of America is seeing a drop in prescriptions, however. While the amount of opioids doctors prescribed fell in nearly half of counties across the United States between 2010 and 2015—and stayed stable in another 28 percent of counties—in about one in four counties, it actually went up. As of 2015, doctors in America’s highest-prescribing counties gave out more than six times as many doses of opioids per capita in their regions than their counterparts in the lowest-prescribing counties. Overall, American doctors are still prescribing three times as many opioids per capita as they did in 1999, and almost four times as many as doctors in Europe. The map below shows which counties are the most prolific prescribers:

(Photo: Gery P. Guy Jr. et al./Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report)

The CDC analysis doesn’t measure whether those prescriptions were safe or warranted—perhaps many were. The wide range of prescription doses, however, suggests that doctors in America aren’t consistent in their prescribing and there’s no consensus about sound opioid prescribing practices, CDC officials write in the JAMA essay.

The study authors examined counties’ demographic data to see if it might explain the differences. Counties with the highest rate of opioid prescriptions tend to have higher white populations than average; to encompass small cities that aren’t part of major metropolitan areas; to have high rates of diagnosed diabetes, arthritis, and disability; and to have high rates of unemployment and Medicaid coverage. These findings bolster some previous work that’s found that, right now, opioid addictions tend to disproportionately affect white Americans. Journalist Sam Quinones has previously documented how unemployed folks in Kentucky used Medicaid to receive pills that they could then sell.

All these results show that progress against unnecessary opioid prescriptions is possible, the CDC team writes. In fact, in nearly half of America’s counties, it seems to have happened. But there’s still a long way to go. The county-by-county data suggests which parts of the country may still need work—often economically struggling towns, away from America’s big cities.