Let’s suppose the polls are right and Republicans take the Senate this week. What does this mean for the next two years and for the 2016 presidential election campaign, which essentially has already begun?

Some political observers have already weighed in on this, suggesting that a unified Republican Congress would be a blessing for the presidential prospects of Hillary Clinton, even while making President Obama’s final two years more challenging. As John Harwood wrote a few months ago:

Republican control of both the House and Senate would provide Mrs. Clinton a clearer target to run against in courting voters fatigued by Washington dysfunction. The longer an unpopular president and his more-unpopular partisan adversaries battle to a standstill, the easier it is to offer herself as a fresh start.

It’s certainly plausible to imagine a united Republican Congress being hopelessly gridlocked. They may pass tax cuts, drastic reductions in services, repeals of Obamacare, and so forth, all of which will be promptly vetoed by Obama. They’ll approve few if any of his judicial nominations or administrative appointees. We could even see another budget shutdown or a face-off over the debt ceiling. The 114th Congress could well be even less productive than the 113th, which is one of the least productive in history.

But would that actually end up helping Hillary Clinton? Do we have any evidence that this sort of jujitsu works? President Truman famously won in 1948 while running against the “Do-Nothing” 80th Congress run by Republicans. But if we examine this more systematically, does one party really have an easier time winning the White House if the other party is running a gridlocked Congress?

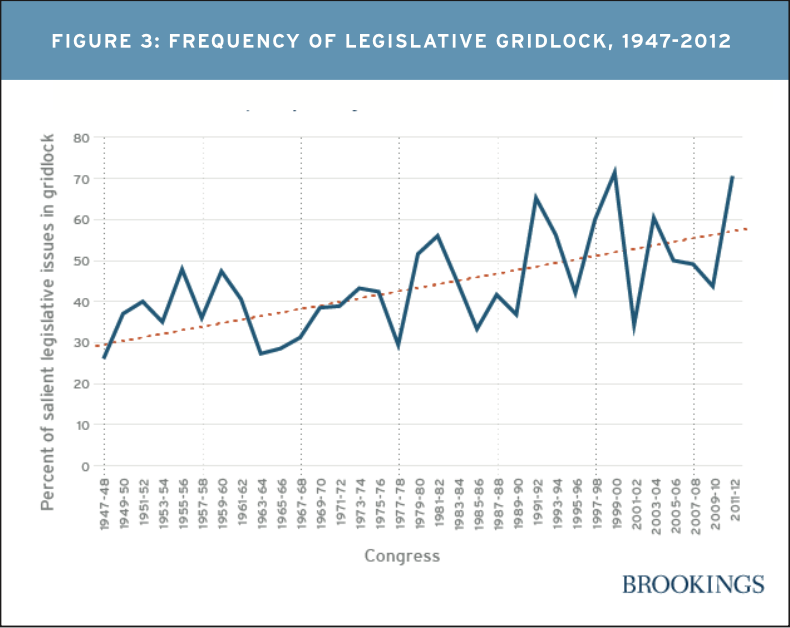

To get a sense of this, I examined Sarah Binder’s evidence on legislative productivity in Congress. She measures gridlock by counting the number of issues mentioned in the New York Times editorial pages over the course of a year and then looking at the number of those issues Congress fails to address. The chart below shows the peaks and valleys of gridlock since the 1940s and the general trend toward greater gridlock as the parties have grown more polarized. (Interestingly, the “Do Nothing” Congress from 1947-48 looks like they actually did something.)

Can we glean much evidence here for the thesis that gridlocked Congresses help the minority party in the next presidential election? It’s interesting to examine some of the spikes in gridlock. The 1981-82 Congress, for example, was relatively gridlocked under Democratic control, and Republicans won a decisive presidential election in 1984. But perhaps there’s too much time between the Congress and the election for that one.

Some other spikes can be seen:

- 1991-92, Democratic control. Democrats nonetheless win a sweeping victory in the 1992 presidential election.

- 1999-2000, Republican control. The Republican Congress appears gridlocked because it spent virtually all of its legislative time on one issue, the impeachment and (unsuccessful) removal of a poplar Democratic president. This doesn’t appear to hurt the GOP, which goes on to win the 2000 presidential election. Even while Gore won the popular vote, he well under-performed how most economic forecast models suggested he should have done.

- 2003-04, Republican control. Republicans nonetheless win the 2004 presidential election.

- 2011-12, split control. Hard to know what to expect from that.

One point to glean from this is that there just aren’t a lot of cases of unified, gridlocked Congresses right before presidential elections, so it’s hard to draw many general lessons from this. Another point is that, to the extent we can tell, voters do not seem to punish a party for running a gridlocked Congress in the next presidential election. (Notably, Republicans fomented a shutdown and a debt ceiling crisis just last year, and now appear poised to make large gains in the Congress and state legislatures.)

Assuming the economy is still expanding in 2016, and assuming her nomination isn’t derailed, Hillary Clinton would have a decent shot at winning that year’s presidential election. But the behavior of the next Congress will probably do little to help her or hurt her.

H/t Thad Hall