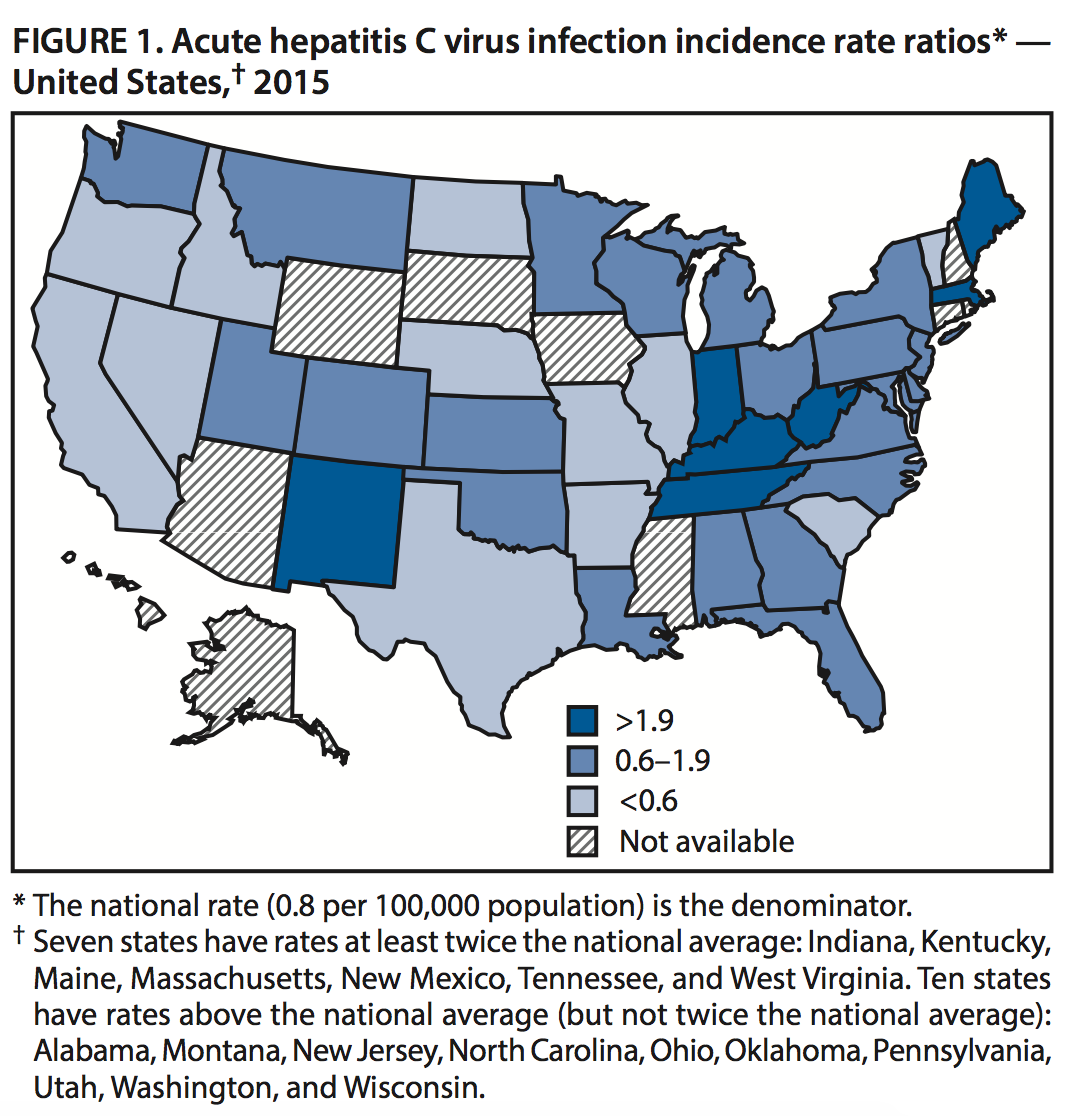

Hepatitis C kills about 19,000 Americans a year, more any other infectious disease—including measles and AIDS—reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And the problem seems to be worsening: Between 2010 and 2015, the number of Americans with hepatitis C nearly tripled, according to CDC numbers, with many of the new cases seemingly involving young people injecting drugs.

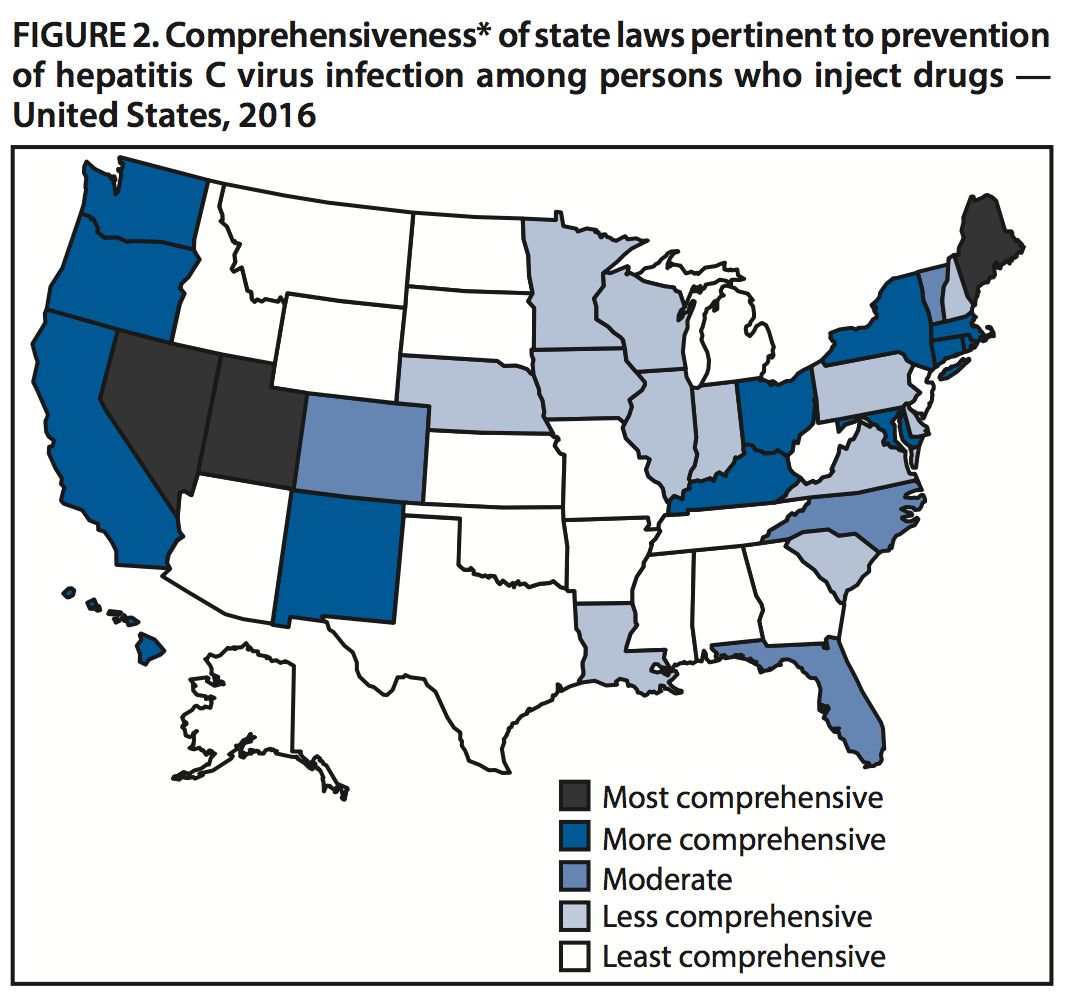

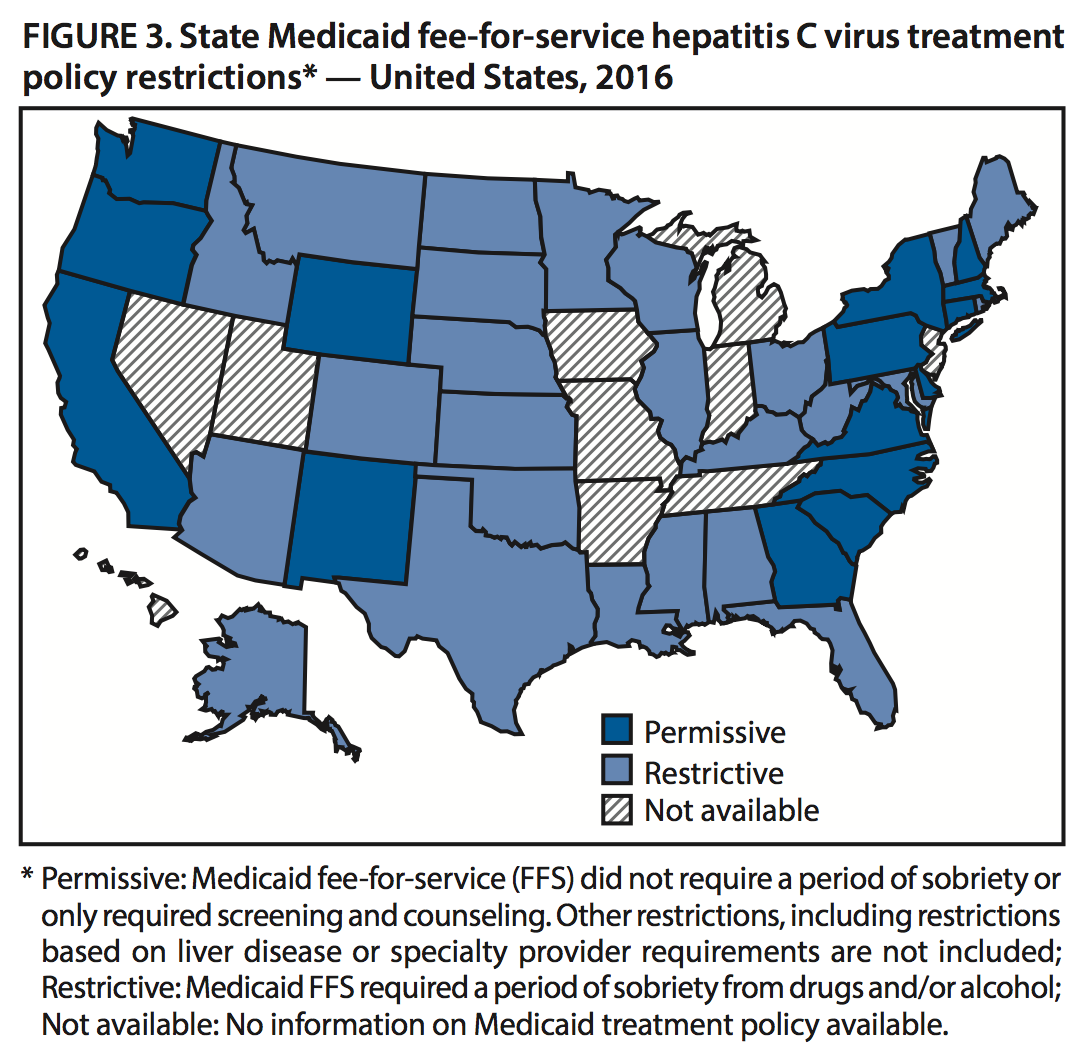

Amid these rising cases, many states lack policies that might help slow the spread of hepatitis C, according to a new analysis from the CDC. Despite the fact that needle-sharing is the primary cause for hepatitis C, not many states have laws encouraging users to only inject with clean equipment. In addition, nearly half of states require that a user is sober before he or she can get treatment for hepatitis C through Medicaid. Such policies leave active drug users untreated and open to infecting others.

Seventeen states have higher hepatitis C rates than the national average, CDC researchers found. Yet only five states cover hepatitis C treatment for active drug users on Medicaid. And only three have what researchers characterize as “comprehensive” laws encouraging clean needle use: Namely, the states authorize needle exchange programs, where drug users can get clean syringes for free or at a low price, and exempt people from drug paraphernalia charges for possessing needles.

(Map: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

(Map: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

(Map: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Laws loosening access to clean syringes and hepatitis C treatment are controversial. Hepatitis C drugs can cost tens of thousands of dollars and many states place various restrictions on whom they’ll pay for through Medicaid. “It is just not feasible to provide it to everyone,” Matt Salo, director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, told NPR in 2015. Advocates, meanwhile, argue that Medicaid should always pay for medically necessary treatment.

Some voters and politicians see needle exchanges as setting a bad example and enabling illicit drug use, although the research suggests otherwise. Even during severe HIV outbreaks, some American politicians have been slow to authorize exchanges.