The Republican Party has taken a lot of criticism in the past few years—from political scientists, journalists, and even some Republican elected officials—for behaving irresponsibly with regard to the nomination, election, and presidency of Donald Trump. It’s an easy accusation to make, but just what is a modern party supposed to do when put in the situation the GOP faced? A plurality of the party’s primary voters said they wanted Trump. Should we really have expected Republican leaders to push back? I’d like to offer an alternative model here, based on actions by Colorado’s Republican Party during 2010.

That year—2010—was a very good year for Republicans across the country. The Tea Party, eager to hold President Barack Obama in check and turn back his signature accomplishments, encouraged record numbers of Republican candidates to file to run for Congress and other offices. Mainstream Republicans, as well as Fox News, did a great deal to fan the flames of the nascent Tea Party movement and encourage the emergence of candidates.

But of course a wave of amateur candidates will inevitably produce some who are not qualified to hold public office. One such candidate was Dan Maes, a Colorado businessman who had never run for office prior to filing for the state’s 2010 gubernatorial race. He managed to generate enthusiastic backing among Tea Party activists across the state and performed well in the party caucuses.

Meanwhile, more conventional Republican figures in Colorado had sought to close ranks behind Representative Scott McInnis for the governor’s race. McInnis, with more than a decade of congressional service, seemed like a solid choice for the nomination, until a Denver Post reporter found that he’d been plagiarizing a series of essays. This story broke just before the gubernatorial primary, tanking McInnis’ numbers; Maes won his party’s nomination.

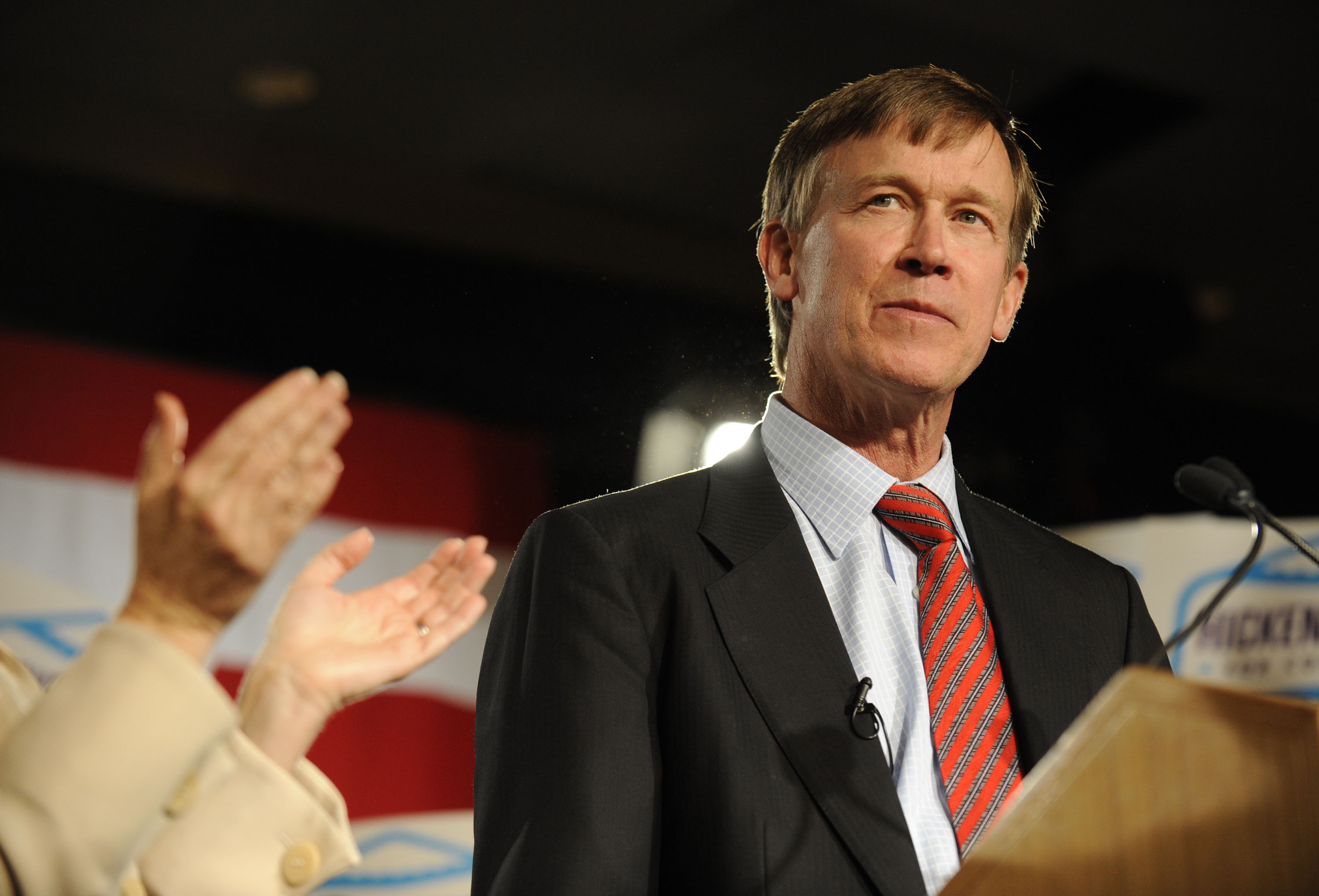

Now, it’s one thing for a party to get stuck with a nominee that many of its leaders don’t like. But Maes was an unusual example. He publicly decried the city of Denver’s participation in a bicycle-sharing program as leading to a United Nations takeover that would undermine America’s freedoms and lead to forced abortions. He pleaded guilty that year to campaign finance violations. He claimed to have worked undercover for the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, which Kansas officials denied. On top of all this, he was a poor fundraiser and appeared to be polling far behind his Democratic opponent, Denver’s then-Mayor John Hickenlooper.

At this point, the state’s Republican Party faced a similar situation to that faced by national Republicans in mid-2016. Their party’s nominating system had picked a poor nominee—someone who seemed unsuited to the office he sought, and possibly a drag on the ticket for other Republicans. The Colorado GOP could have done what national Republicans did in 2016—close ranks behind its nominee and hope for the best, worrying about the challenges of governing later. 2010 was shaping up to be a good year for the party anyway, and a unified GOP might have prevailed against Hickenlooper.

Instead, Colorado Republicans abandoned their own nominee. Many party leaders met with Maes to encourage him to drop out of the race. When that failed, they endorsed a third-party candidate—former Colorado Representative Tom Tancredo, running under the banner of the American Constitution Party—as the “real” Republican. This point really can’t be overstated: Prominent party leaders decided that their own primary voters had made the wrong choice, and they urged a vote for someone other than their own nominee.

Also importantly, this swing in endorsements mattered. Republican voters abandoned Maes in droves. In the end, Tancredo took 36 percent of the vote, Hickenlooper got 51 percent, and Republican nominee Dan Maes got just 11 percent, nearly relegating the GOP to minor party status under state law.

(Photo: Matt McClain/Getty Images)

This hardly proved fatal to the party. Republicans still managed to take over the state House of Representatives, as well as the offices of secretary of state, treasurer, and attorney general. They went from controlling two of the state’s seven House seats to controlling four of them. And the party has remained competitive in subsequent elections, while the American Constitution Party has returned to its pattern of winning very small percentages of the vote.

What was different between the Colorado Republican Party of 2010 and the national Republican Party of 2016? Why was the former willing to take a dive rather than install an irresponsible candidate in its top post while the latter made the opposite choice?

For one thing, the offices are obviously different. The stakes for winning or losing the governor’s office are high (including a great deal of budgetary influence, a major role in redistricting, control of patronage offices, a powerful fundraising position, etc.), but they don’t come close to the presidency and its outsized role in staffing government and setting policy.

It also may be that Colorado Republicans are just different from national Republicans in important ways. It was the RNC’s Colorado delegates, after all, who refused to vote for Trump and led the walkout during the 2016 convention. As one delegate to the Republican state convention that year explained his unenthusiastic vote for Ted Cruz to me, “I’d rather lose one election than the next four or five.”

Regardless, the Colorado example remains an important counter to national Republicans who claim that they had no choice but to go along with their voters’ wishes in 2016. A party doesn’t have to double down on its errors. It can take a loss and live to fight another day.