Queer-centric, mainstream publications have been failing the diverse community they purport to represent. Earlier this year, when black queer rapper Mykki Blanco tweeted several critiques of what he called the “White Gay Media,” he brought new attention to the overwhelming whiteness of publications like The Advocate, Instinct, and Out.Using the hashtag #GayMediaSoWhite, social media users collected magazine covers featuring white, and, in many cases, heterosexual, celebrities. They contrasted them with images of black victims of homophobic violence — a nod to how outlets cover diverse members of the LGBT community primarily when their stories are tragic.

Recognition of mainstream gay magazines’ narrow focus on predominantly upwardly mobile, white, gay men goes back to at least 1992, when the New York City-based zine Pussy Grazerpublished what looked like excerpts from Out magazine’s market research. The alleged marketers portrayed the gay readership as a lucrative set, “a dream market,” in the words of a quoted Wall Street Journal article. Researchers, meanwhile, have recognized the myopic gaze of gay magazine advertisers for some time: A 2008 study published in the Journal of Homosexuality ascertained that, between 2001 and 2004, over 95 percent of advertisements in the pages of Out, The Advocate, Genre, and Instinct magazines depicted Caucasian males.

This year, Blanco’s remarks inspired countless news articles and an informal study of gay magazine covers in the last five years by Fusion. From June 2011 to May 2016, writer John Walker found, Out, The Advocate, and Attitude featured white people on 85 percent of their covers and straight, white, cisgender men on 40 percent. Queer people of color only constituted nine percent of the magazines’ 224 cover models during this period.

Responding to this gap in coverage, a new breed of queer publications is stepping up to the plate. Publications like Hello Mr., Jarry, GAYLETTER, Fop, The Tenth, Cakeboy Magazine, and Elska are creating their own spaces to speak to and about these underserved pockets of the LGBT community. These bespoke zines, which boast beautiful designs and glossy prints, nurture smaller, more localized communities than their more mainstream competitors. Nevertheless, with ambitious reporting and active online presences, they’re endeavoring to prove that niche publications with an eye toward diversity can find a wide readership in the social media era.

The history of zines is a long one. People have self-published pamphlets and leaflets since at least as early as 1776’s Common Sense, and yet the zine as we know it today was born in the late 20th century. In The Book of Zines, Chip Rowe gives a simple and short description of these publications: “Zines (pronounced ‘zeens,’ from fanzines) are cut-and-paste, ‘sorry this is late,’ self-published magazines reproduced at Kinko’s or on the sly at work and distributed through mail order and word of mouth.” Zines’ do-it-yourself aesthetics, idiosyncratic areas of coverage, and focus on local communities bred a new generation of creators who used these projects, whether tied to science-fiction fandoms, punk culture, or political activism, to connect and bring people together. In the late 1980s and ’90s, for instance, zines were instrumental in the rise of racial movements like Queercore and Riot Grrrl.

Today’s queer imprints remain wedded to the format’s dedication to specific communities — and yet, with high-quality production values and wide dissemination on social media, they hope to reach a broader audience than the hand-crafted zines of yore could have imagined, or wanted to.

The Tenth seeks out and explores diverse LGBT communities; it doesn’t presume, its creators say, to speak for them.

The Tenth, a biannual zine covering gay black life, doesn’t presume to be for everyone. The Tenth is perhaps most distinct for its commitment to local stories. For its third issue, its editors and collaborators spent half a year creating what they deem “an authentic epistemology of contemporary Los Angeles.” The Tenth has also featured editorials on an alpaca farm in Michigan and the vibrant queer black community in Detroit; geographic subjects range widely, and a meditation on the illusory appeal of Los Angeles, a chat with BLACKtivists in Boston, and illustrations depicting South Beach, have also appeared within its pages.

The Tenth seeks out and explores diverse LGBT communities; it doesn’t presume, its creators say, to speak for them. “We’ve been reaching out, meeting people in different places, so we don’t just bring our New York friends,” Khary Septh, the creative director behind The Tenth, told Dazed upon the launch of his project. “We’re all from somewhere obscure. We’re not all from a really cool part of New York.”

The focus on small communities may seem counterintuitive; The Tenth, after all,is a new publication that’s presumably in need of a wide reach to survive. Keeping it afloat hasn’t been easy: One member of The Tenth’s editorial team told NPR’s Codeswitch that it struggled to find advertising dollars to secure funding for its first issue.

But The Tenth’s survival is in keeping with larger trends in the Internet at large, as Karen McIntyre notes in her study of the evolution of social media. “Niche sites have taken over social media in the past decade, while targeting a mass audience has become the exception,” she writes. MySpace’s adjusted business model following its user base decline, McIntyre indicates, is just one example of the ways social media giants have pivoted away from mass audiences to court increasingly niche populations.

Some of newer queer-centric publications are, however, intentionally covering audience-friendly topics. Sean Santiago, the editor and creative director at Cakeboy, says he is interested in “amplifying voices that have something more meaningful to contribute to the broader conversation around the culture.” One need only glance at the latest issue of that queer-creator-driven magazine to see what that looks like: not only does the issue feature South African art duo FAKA on the cover, but, inside, it covers London-based singer Shivum Sharma, video and performance artist Kalup Linzy, and a photography spread by Rakeem Cunningham. Topped with a cheeky profile of gay video artist Colby Keller, Cakeboy aims to be a newsstand-friendly publication that champions a wide array of diverse voices that would not ordinarily be featured in mainstream gay magazines.

Perhaps because it’s essential to their continued survival, these queer-centric are evolving to meet the demands of their readers. As Liam Campbell, the editor and chief photographer ofElska magazine explained to me in an email, he’s had to actively work to diversify the content of his publication — even if it’s already a novel, more inherently inclusive publication on its own. Campbell describes his zine as a “part-intellectual queer pin-up mag and part-sexy anthropology journal.”

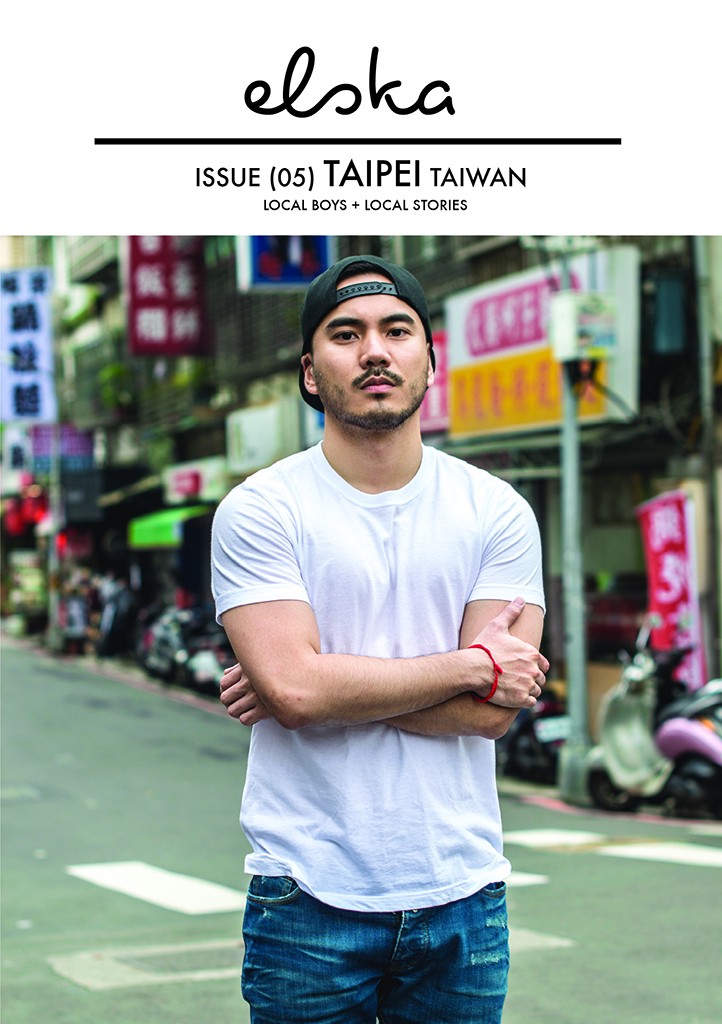

True to the its founder’s professional background (Campbell is a former flight attendant) every issue of Elska is set in a different city. The first four issues read like a jet-setting road map of Europe: Lviv, Berlin, Reykjavík, and Lisbon. In Elska’s pages, Campbell includes profiles and interviews of local gay men, wanting, as he says, to do for readers “what travel does … to open people up to new places, new people, new ideas.” The men featured in Elska aren’t just beautifully photographed models, but also gay men armed with voices and stories; they are collaborators in their own right.

In looking over the ever-growing roster of men he and his contributors had been amassing, Campbell noticed that, given the European-centric content of his first four issues, he was presenting a narrow vision of the community he had hoped to broaden. It’s partly what inspired Campbell to head East for his next issue producing the fifth iteration of his zine in Taipei.

Elska publishes racier material than what readers might see in mainstream publications; this, too, figures into Campbell’s project of pushing back against limiting media representations. The “Elska Boys” in the Taipei issue were photographed in ways that framed them within an overtly erotic gaze — lounging in bed naked staring into the camera, shot outdoors shirtless, smiling gleefully while dropping trou in public. It’s Campbell’s attempt at pushing back against racism in the gay dating world, which often masks itself in the language of preference. The racial bias that OkCupid found in studies in both 2009 and 2014 for heterosexual matches isn’t absent from gay applications like Grindr — gay, bisexual, and other same-sex attracted men, one 2015 study found, hold fairly tolerant attitudes toward sexual racism online.

With some of these publications, print runs are still limited and they’re only available in select cities around the world — Elska and Cakeboy can be found in Berlin, New York, and Los Angeles, for instance, among a few others. Nevertheless, their websites (which sell past issues) and social media efforts broaden their reach. Accompanying GAYLETTER’s latest issue, which includes a piece titled “Sissy Daddy; Edmund White,” is an online-only, NSFW video produced about the racy photoshoot. Jarrywill be in Atlanta in July to celebrate Steven Satterfield, whom it profiled in a piece in its latest issue (“Steven Satterfield’s Atlanta”). Crowdsourced marketing tactics, meanwhile, encourage readers not just to check out editorial content, but also to take ownership over sustaining the business. Readers are encouraged to buy branded merchandise (T-shirts, totes, aprons), but also to share social media posts with mag-inspired hashtags (#MrTattooTuesday, #JarryType, #unbothered), and attend launch parties that embrace them as fellow collaborators in these projects.

The impetus is to explode the idea of a gay magazine’s readership, moving it from being perceived as a mass of passive consumers to individuals that are actively engaged with their preferred magazines. Though some of this work takes place via shareable video entries and on social media, today’s gay zines remain wedded to the analog spirit of the zines from the 1990s: They are just as committed to serving their community of readers. No doubt Glennda Orgasm, one of the founders of Pussy Grazer who decried the “sea of white faces” that was the visible gay community in the 1990s, would be heartened by these new, broader visions of what LGBT readers look like.