In 1996, when I was 13, I believed Jesus Christ had called me to be the president of the United States of America. As leader of the free world (and a surgeon!), I would lead God’s people through the apocalypse, and into his light.

Christians often debate whether the rapture will happen before or after all the pain of the apocalypse. These believers fall into three main camps: pre-tribulation, mid-tribulation, and post tribulation. I was surrounded by pre-tribbers and often prayed at night that the rapture would happen post-tribulation, just so my political plans wouldn’t go awry. But just in case, I plotted alternate routes in my journals from the ages of 13 to 15.

I wanted so much to be important. And in America, being president is the most important thing you can be. But women were never president. Even at the time, the idea felt like a manifestation of all the things I wanted so desperately to escape — the patriarchal faith, the future my parents outlined for me of family and home. But if you were smart enough and good enough, then you could escape, you could be important. It’s clear to me now, I never really wanted to rule, I just wanted to be set free.

In 1995, my family moved from Texas to South Dakota. We were a motley group of seven kids, soon to be eight, driving across America in our 15-passenger van. We were home-schooled and Evangelical, proto-Duggars, who had all taken purity pledges and were under orders only to court — never to date. And we looked the part too. Except for me, my sisters all had long hair. We wore jean skirts. My diary from that year reads like a primer in how to be a holy teenager.

We had left everything. My parents were looking for a fresh start for their marriage, but we didn’t know that then. All we knew was that we were going. My mom joked that we were like the Ingalls family from Little House on the Prairie, and our van a covered wagon. The first day we arrived in South Dakota we stepped outside in a Perkins parking lot and the wind whipped pellets of snow into our faces. My sister Jessie sobbed when the cold hit her braces. That night, a fertilizer plant exploded just miles from our hotel in Sioux City. Welcome to South Dakota.

That first year in South Dakota, I wrote anguished entries about not loving God enough, about not following his commands. In these pages, I agonize every time I think about a boy in church instead of the sermon. I also talk a lot of shit about boys not being as good as me at memorizing Bible verses. In one entry, I talk about how I boldly quit my job babysitting at a woman’s Bible study: “I’m just not cut out for baby stuff.” In another entry, I envision my future husband and our children. One would be a boy I would name Clayton Scott (no significance to the name, I just loved cursive Y’s and double consonants). For many of the entries, at their most vulnerable and revealing parts, I write “pun intended.” (They aren’t actually puns, but I didn’t know what a pun was.) The phrase was a signal to anyone who might possibly stumble upon my writing that I was clearly joking about my love for Tim B. or that time when I wrote in very small handwriting, “Does God even exist?”

Pun intended.

But the main narrative thread throughout these journals is my full-blown delusions of grandeur. I write about receiving the gift of prophecy because of my certainty that the Dallas Cowboys would win a particular game. “I think my spiritual gift is prophecy! I won’t be like Isaiah or Jeremiah but God talks to me and tells me things, things I don’t like to brag about to people,” I wrote. Then, a few lines later: “I pray to God that I could stay for the end times to help more people come to know the Lord and at his [second] coming I run into his arms.”

And then, just a few days later on November 5, I write about the election.

I was allowed to stay up and watch the news that night, which was a big deal because, until the move, our television had been kept in a hall closet and was only rolled out for family movie night on ABC or Dallas Cowboys games.

In 1995, the Left Behind series had been released and, like many holy teens at the time, listening to our DC Talk and Michael W. Smith, I was obsessed. I read and re-read the book as we traveled to South Dakota, and again as I spent my lonely days poring over algebra worksheets at the kitchen table. I also spent a lot of time parsing Revelation, making careful notes in the margins of my Bible. We didn’t have the Internet then and only one Biblical concordance, so most of my time was spent imagining interpretations for the words on the page. What might a seal be? What is a scroll? What does it look like to see a woman clothed in the sun?

In the book of Revelation, the woman clothed by the sun is attacked by a dragon and she is given wings to fly. The dragon sends a flood from his mouth to consume her, but the Earth protects her and swallows the water. The dragon then attacks her children but is ultimately defeated.

Scholars interpret this woman as a symbol representing the church of Christ, or the New Jerusalem. The Latter-Day Saints believe she is a symbol of the new political system that will grow out of the Mormon church. Even when she is interpreted as the Virgin Mary, she is still seen as representing the church. Scholars tend to treat the figure analogically, allegorically, and so forth — basically as anything other than an actual human woman. Yet in my own isolated childhood, I interpreted her as a powerful female ruler, one who would defeat the dragon and bring about the kingdom of God. And I wanted to be her.

So in 1996, as I watch Bill Clinton get re-elected and hear my father grumble about women who only vote for the “hot guy” and listen to his conspiracy theories about how one day, if not today, the electoral college will be used to usurp the will of the people and bring about the end times, I begin to see myself as that woman, clothed in light and power. I want to be her.

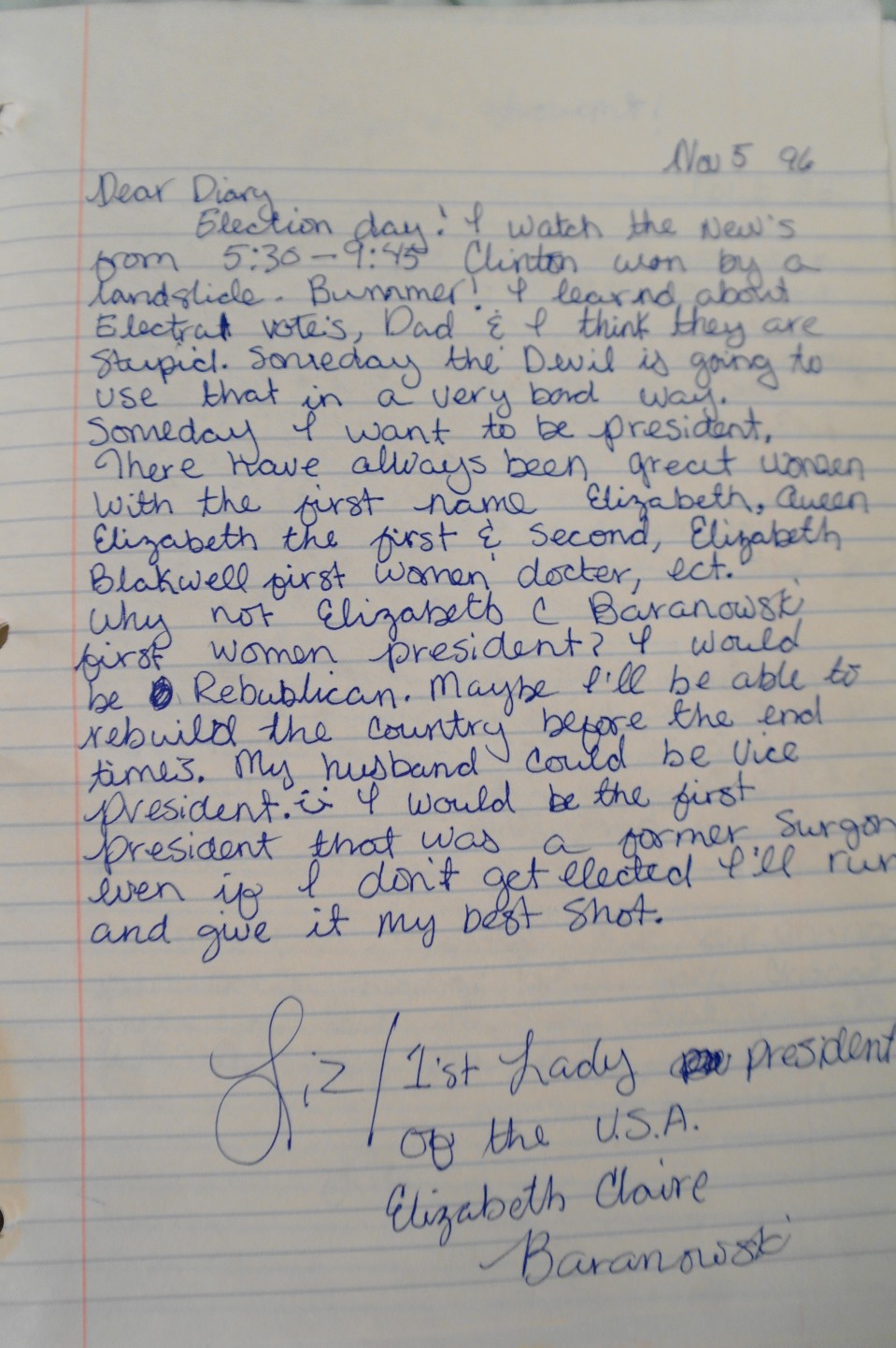

That night, I open my diary and write [sic everything; I was 13]:

Dear Diary,

Election day! I watch the new’s from 5:30–9:45. Clinton won by a landslide. Bummer! I learned about the electral votes. Dad & I think they are stupid. Someday the Devil is going to use that in a very bad way. Someday I want to be president. There have always been great women with the first name Elizabeth, Queen Elizabeth the first & second, Elizabeth Blackwell first women doctor, etc. Why not Elizabeth C. Baranowski first women president? I would be Republican. Maybe I’ll be able to rebuild the country before the end times. My husband could be vice president J I would be the first president that was a former surgeon. Even if I don’t get elected I’ll run and give it my best shot.

Liz / 1st Lady President of the USA

Elizabeth Claire Baranowski

Twenty years later, I watched Hillary Clinton receive the Democratic nomination to run for president and sobbed. This time, there was no bummer. Just joy.

Elizabeth Claire Baranowski has gone through a lot in 20 years. The year following Clinton’s re-election, in a fit of rebellion, I would change the spelling of my nickname to Lyz. The year after, I would scream at my father that Republicans were stupid. (Fifteen years later, he’d come to agree.) I’d ride in the back of pick-up trucks listening to Nate Dogg and Black 47. I’d write “Rise up, proletariat!” on my jeans and carry around a copy of the Communist Manifesto. And then, in college, I saw The Vagina Monologues, smoked some, drank a little, and said “fuck” a lot. I learned that writing was a way for me to speak without being interrupted by men. I gave up my plan of being a surgeon when I fell in love with William Faulkner. I graduated from college and married. I stopped believing in God. This time, no pun intended. And then I believed in him again. And finally, 20 years later, I saw Clinton on that stage, in the white outfit. In that moment, I was once again that 13-year-old girl in her attic room with ivy stenciled on the ceiling, just wanting to be given wings so she could fly. Just wanting the Earth to swallow the flood that threatened to consume her.

There isn’t a lot of room for women in the Bible. The women are there, but they are always knocking around in the greater stories of men and eventually silenced by their narratives. And while little Elizabeth Baranowski was wrong about so many things, she did find a loophole: She found a place for herself in a faith and a tradition that constantly told her that what she wanted to be was the exact opposite of who she was supposed to be.

I did not become president. I am not sure if I am entirely free. But I look at Clinton and I think that maybe, one day, I will be.