As Democrats racked up a series of major victories in Tuesday’s elections, the ensuing analysis is, to many Californians, a familiar one. The story coming from Washington has focused on how Tuesday’s results reflected a full-blown rebuke of a Republican Party that, just a year ago, propped up one of the most politically polarizing presidential candidates in American history.

California lived through a version of this narrative two decades ago. Some of the peripheral details are different—the California Republican in question, former Governor Pete Wilson, was not anything close to the disruptive force that Donald Trump has shown himself to be in the first year of his presidency. But Wilson’s 1994 re-election did usher in a new era of California politics, and had long-term consequences for the California Republican Party.

In the wake of Wilson’s second term, Latinos moved overwhelmingly to the Democratic Party. Republicans also lost middle-class voters in the process, and the GOP has been relegated to the political sidelines of state politics ever since. Today, Republican Party registration in California has slipped to less than 26 percent statewide.

If this week’s election was a blast from the past for California, then the state’s 2018 elections may provide a glimpse of America’s future. More than 20 years after Wilson’s re-election brought about the beginning of the end of the California Republican Party, California is essentially in a post-Republican phase. Next year’s elections in California can offer a window into what comes next, not only for Republicans, but for Democrats.

Wilson’s election accelerated the maturation of Latino politics in California, and Trump’s election may do the same for ethnic politics nationally.

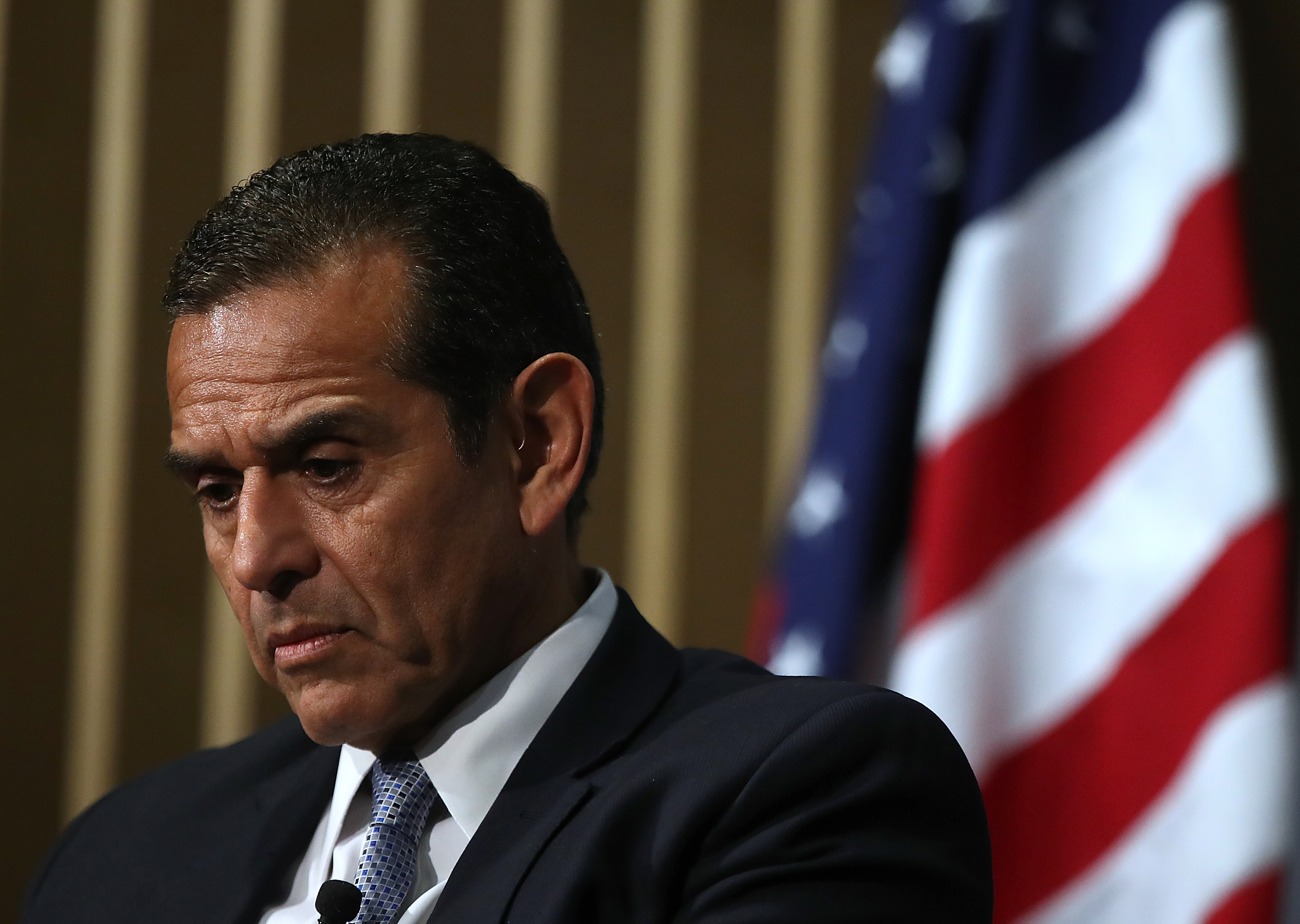

Pan out wide enough and Latinos will look like block voters—they support Democrats over Republicans better than three-to-one. But in post-Republican California (Democrats currently hold two-thirds majorities in both legislative houses, and every statewide elected office) it no longer makes sense to view the Latino vote, or any politics, through merely a partisan lens. Zoom in just a little bit and you’ll see a more nuanced portrait of Latino politics. While new faces like state Senator Kevin De León are trying to rally the Bernie Sanders coalition against 24-year incumbent Senator Dianne Feinstein, fellow Democrat Antonio Villaraigosa is preparing a gubernatorial run that puts a focus on the plight of the Central Valley, and is banking on support from the state’s business community if he makes a fall run-off.

We see this split elsewhere. Latinos are both the progressive core of the new California politics, and also the heart of the business-friendly moderate Democrats. While De León talks climate change at the Vatican, state officials like Assemblymembers Raul Bocanegra and Rudy Salas have been pivotal in blocking some of the more radical environmental legislation in Sacramento, and voting with oil companies and other business interests on a host of issues. Even Secretary of State Alex Padilla and Attorney General Xavier Becerra made their political reputations as pro-business Democrats who received as much support from corporate donors as they did from grassroots activists.

Latinos make up a plurality of the state’s residents, but still just 25 percent of its registered voters. To win statewide office, then, it is not enough to simply win the Latino vote. Latino candidates must still build broad coalitions that are not primarily ethnic-based.

The path for building that coalition depends on the candidate. This is particularly true under California’s relatively new election rules, which allow the two top vote-getters to advance to a November run-off. That means instead of the top Democrat facing off against the top Republican in the fall, we could potentially see two Democrats go head-to-head in November of 2018. That happened in California’s United States Senate race in 2016, and it could become the new normal in statewide contests unless Republicans can stop their political erosion.

But it can also change how Democratic candidates target voters. Without a Republican to vote against, Democrats have to campaign harder for a Latino vote that is still up for grabs.

(Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

We saw some evidence of this in 2016 when Kamala Harris faced off against fellow Democrat Loretta Sanchez in the race for a U.S. Senate seat. True, the Sanchez campaign was underfunded, and she was an imperfect candidate. But Harris also refused to cede the Latino vote, campaigning hard in Latino parts of the state, and racking up numerous endorsements from Latino elected officials. Harris bested Sanchez in majority-Latino Los Angeles County by 20 points, and won the Latino vote statewide, according to exit polls.

As the Latino electorate continues to evolve, other factors like region, age, and income are proving to be more dominant than any ethnic political identity. Many of California’s more moderate Latinos leaders hail from inland communities—either Southern California communities stretching from the San Fernando Valley east through Riverside and San Bernardino—or Central Valley cities like Bakersfield and Fresno.

De León is now making his appeal to younger voters and liberal coastal whites—the same coalition that carried 46 percent of the Democratic vote for Sanders against Hillary Clinton in 2016. Sanders built a national coalition that included younger voters, and, in California, those younger voters are more likely to be Latino, and less likely to vote than Gen Xers or Baby Boomers, according to data from the Public Policy Institute of California.

But Sanders ultimately won just three of the 12 California congressional districts represented by Latinos. Clinton ran strongest in Silicon Valley and the suburbs of the Bay Area and Los Angeles. That is the heart of the Democratic establishment where both De León and Villaraigosa must make inroads to build a winning statewide coalition against another Democrat.

The presence of two very different kinds of Latino politicians on the ballot at the top of the Democratic ticket shows the maturity of Latino politics in California. Win or lose, the ability of De León and Villaraigosa to make inroads in 2018 may well set the course for the future of Latino politics.