To those who were listening, President Barack Obama’s call for a national mandatory paid sick leave law at last month’s State of the Union address probably sounded more like a progressive suggestion than it did a policy objective. After all, in the post-Obamacare world, the Republican Congress has assured that very little, if any, of the president’s agenda is worthy of its time.

But with his endorsement of a paid sick leave law—part of Obama’s “middle class economics” plan, which included middle-class tax cuts and free community college tuition—the president joined a battle that’s been waging in the states for the past eight years.

Mandatory paid sick leave is a government policy position that requires businesses of a certain size to give its employees a certain amount of time off. Seems simple. But the fight over such a law has actually made and broken political careers, pitted Democrats against Democrats, business trade groups against workers, state governments against local municipalities. And it’s a policy, according to the data, that seems to contradict just about every philosophy business interests have been telling us about government burdens.

“Businesses always claimed doom is just around the corner any time you try to increase the lives and fortunes of working people,” says Dan Cantor, national director of the Working Families Party.

Conservatives often reject the idea on principle—that it oversteps the bounds of government’s role in the private sector. Liberals, on the other hand, often chalk it up as a basic right for workers. A number of states and municipalities have now enacted mandatory paid sick leave and the data show conclusions that go way beyond the philosophical debate.

Exhibit A: Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter. Less than a month after the State of the Union, Nutter, a Democrat, signed that city’s paid sick leave ordinance into law, making Philly the second city this year to do so. Philadelphia’s new law says that businesses with 10 or more employees must allow workers to accrue at least one hour of paid sick leave for every 40 worked. Other cities’ and states’ laws around the country have been written similarly.

Nutter’s history on paid sick leave makes the timing of this statute particularly interesting. Nutter actually vetoed prior legislation in 2011 and 2013, citing conservative arguments about economic burdens on business and the idea that a Philadelphia law would be bad for the economy.

That may seem at odds with where the Philadelphia mayor is coming from—a dark blue city where Democrats outnumber Republicans by about eight-to-one. But Nutter’s not the first liberal to mount opposition to this controversial law.

In 2008, Connecticut became the first state to seriously debate such a bill in its legislature. Mandatory paid sick leave there was lobbied for by the labor-backed Working Families Party before basically anyone else, and would have forced earned sick days at businesses with more than 50 employees throughout the state. The Connecticut bill died three times in the legislature, but rose to prominence again during the 2010 gubernatorial primary, in which Democratic foes Dan Malloy and Ned Lamont attempted to distinguish themselves in a race where most big issues were uniform. Malloy supported paid sick leave; Lamont did not.

Lamont, a businessman who had lost to Joe Lieberman for a Senate seat in 2006, said he would not support a paid sick leave bill. “I do believe it sort of sends the wrong signal out there at a time when we have a very high unemployment rate, and I’m doing everything as a candidate for governor to recruit, to expand job creation in our state,” he said shortly before announcing his campaign.

Lamont’s sentiment was echoed by business and restaurant associations across Connecticut. In a Register Citizen editorial endorsing Lamont in the primary, the paper’s editorial board used Malloy’s support of paid sick leave as part of its rationale. “Lamont knows what a career politician like Malloy is deaf to—that putting yet another mandate on business at this critical juncture for Connecticut’s economy would be insane. It’s about tone, and priorities, and independence,” the board wrote.

But Malloy won, and Connecticut soon became the first state in the country with a mandated sick leave policy.

The paid sick leave policy was opposed vigorously by business groups, particularly the 10,000-member Connecticut Business and Industry Association and the Connecticut Restaurant Association. Both groups argued such a law would drive new business out of state and hurt current business’ profits. Rather, requiring all businesses give their employees time off was supposed to cut into profits, freeze hiring, and chase new commerce out of the state.

“Businesses always claimed doom is just around the corner any time you try to increase the lives and fortunes of working people,” says Dan Cantor, national director of the Working Families Party. “We pushed the rock up the hill in Connecticut, but it’s getting easier each time.”

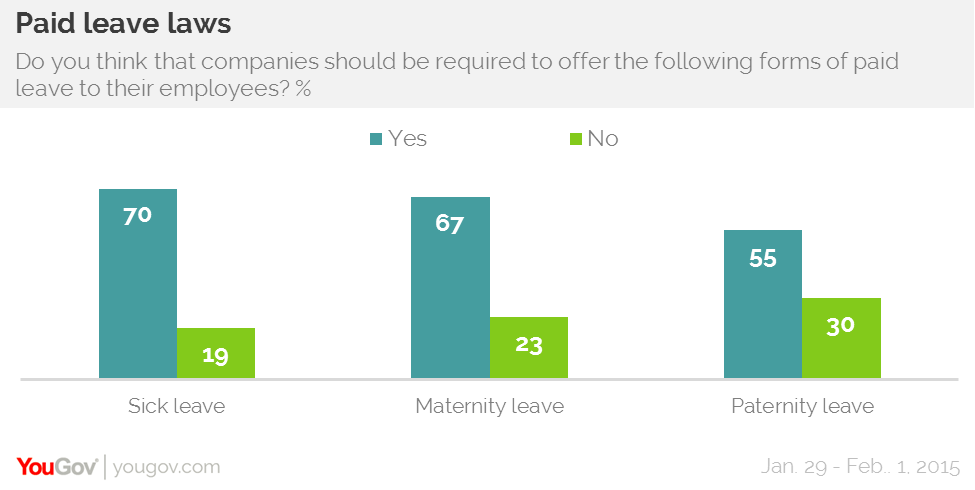

After Connecticut, that push continued. Residents of Massachusetts; Montclair, New Jersey; and Trenton, New Jersey, were all asked via ballot referendum if they supported paid sick leave. They did. Residents of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, voted overwhelmingly in favor of a ballot measure, with 69 percent supporting. Nationally, a 2013 YouGov poll found 74 percent of the U.S. public (Democrats, Independents, and Republicans) support mandatory paid sick leave.

Similar bills passed in 17 cities, coast to coast. This has happened in spite of big business-aligned conservatives enacting laws in 11 states barring local municipalities from putting their own paid sick leave bills into law (the most infamous being Wisconsin, which overruled the Milwaukee ballot measure).

Data collected by jurisdictions that have passed paid sick leave show that most of what the naysayers predicted about such a law is false.

When Bloomberg News looked at three separate studies concerning the effects on San Francisco’s, Seattle’s, and Connecticut’s business climates post-sick leave, the consensus was overwhelmingly positive.

In San Francisco, just one in seven businesses said profits were hurt by paid sick leave. On costs, in Connecticut, a majority of businesses surveyed by the Center for Economic and Policy Research at the City University of New York found either no increases in costs, or less than a two-percent increase.

Meanwhile, about one in six Connecticut businesses, one in 10 San Francisco businesses, and one in 12 Seattle businesses have reported responding to paid sick leave by increasing prices for the consumer.

Other issues pushed by detractors, like abuse of time off by workers and the need to cut other benefits due to sick leave mandates, have proven mostly moot. In Connecticut, just one percent of businesses report cuts to wages. In San Francisco, just seven percent said the same, and in Seattle, just over six percent.

Meanwhile, about one in six Connecticut businesses, one in 10 San Francisco businesses, and one in 12 Seattle businesses have reported responding to paid sick leave by increasing prices for the consumer.

Such findings led the author of the Bloomberg story to conclude that “mandating paid sick leave has limited effect on businesses, workers and consumers. That doesn’t solve the philosophical debate; it just shows that this is an argument about something bigger than economics.”

This sort of information has been argued by the Working Families Party and other state organizations—like the left-leaning Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center, whose positive statistics on paid sick leave were often cited by proponents during Philadelphia’s seven-year battle—but new, independent information based on the law being in place will likely help push paid sick leave over the edge in places where new and expanded policies are currently being debated.

“[Our research] was never decisive in itself for some legislators, but what’s exciting here is that now the opposition cannot say anything that isn’t immediately discredited…. Business groups still say they’re going to lay people off but there’s no actual evidence to support them,” says Cantor of the Working Families Party.

And for those politicians seeking mass approval in the coming days, support for this “middle class economics” idea could prove important for coming elections.

After Philly Mayor Nutter gave his stamp of approval, presumptive Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton endorsed the new Philly law, which goes into effect in May, via Twitter.

“Good week for #Philadelphia,” Clinton wrote, with a link to a Philly.com story about the sick leave ordinance. (Nutter’s signature, of course, came the same week the Democratic National Committee announced that the 2016 National Convention would take place in Philadelphia.)

Assuming this trend continues, paid sick leave will likely become a much-debated topic in the 2016 elections. And assuming the overwhelming amount of data is correct, conservatives may want to begin shifting their allegiances.