In the most recent print version of the European Dispatch column I point out that some health care plans are more “monolithic” than others, meaning some involve more or less government control. The British system is true socialized national health, with a government body that pays doctors and runs medical centers. The German system is heavily regulated, but largely private — it relies on no public insurance and only some public hospitals. In between fall the “single payer” schemes — systems like Canada’s, which offer government insurance to cover expenses in a largely private system.

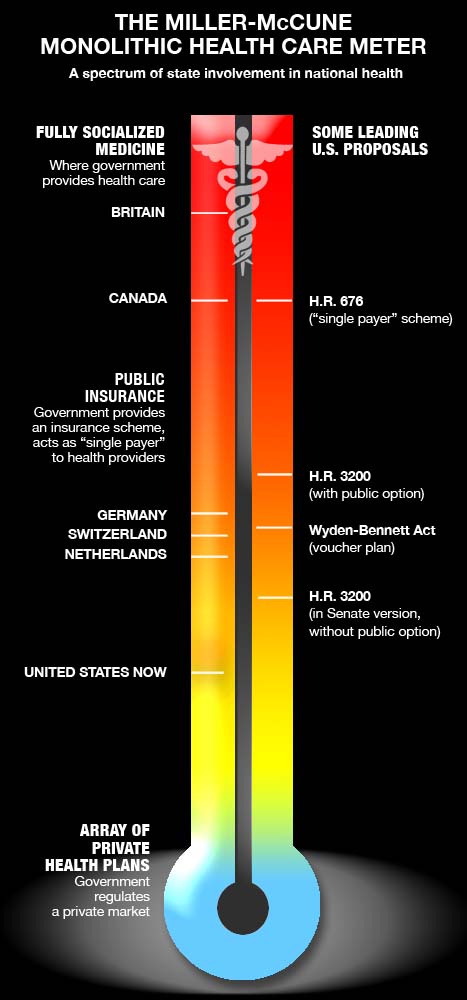

To get a handle on this matter of state control, we’ve mocked up a handy graphic. The idea is to show (crudely) how much direct involvement the state has in health systems around the world and how the bills moving through Congress compare. The metric is over-simplified but for our purposes: Your health scheme is monolithic when the government 1) collects your money, 2) handles your insurance, and 3) administers the health care.

Two of the above are true in America for welfare recipients and retirees — Medicare and Medicaid are public insurance schemes that pay for private medical treatment. Only the first is true in Germany, where the government heavily regulates (and even pays) insurance companies, but lets them handle actual coverage. Private doctors deliver the aid and comfort.

The U.K.’s National Health Service fulfills No. 1 and No. 3, rendering No. 2 meaningless because no one needs an insurance middleman when most of the country pays for what amounts to a national HMO. But private health insurance exists in Britain for people (with enough money) who want to opt out of the NHS.

Canada has a true “single payer” plan, in the sense that the government runs one big insurance fund to cover most citizens. It then pays directly to a web of mostly private doctors and hospitals, though some hospitals are government-run.

Nobel Prize-winning economist and New York Times op-od columnist Paul Krugman has argued that the American plans now being hatched in Congress resemble the Swiss model more than anything else. He could have compared them to the German and Dutch models, too, but the argument needs refining.

First, an older House bill, H.R. 676, proposes a true single-payer plan like Canada’s — essentially a big expansion of U.S. Medicare. It won’t pass. This year’s House bill, H.R. 3200, leaves the insurance industry intact but provides for a public insurance option. The Senate may water down that provision and resort to “co-ops,” which historically don’t give the private insurance industry much competition. But all these alternatives lack a crucial element known to the German, Dutch and Swiss — namely a hidden single payer.

Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands get along fine without a public option; they have strong traditions of private care and lots of insurance schemes to choose from. But the government collects money so it can act as a sort of back-door subsidizer for those insurance schemes. This public pool of cash is crucial because it can reverse incentives for an insurance company when it comes to needy patients: The sicker the patient, from a German insurance company’s point of view, the better — because an infirm patient on the rolls means the company can claim more cash from the government pool.

Another bill languishing in the Senate, the Wyden-Bennett Act, uses just enough of this hidden-pool logic to create a voucher system (and a real marketplace) for American insurance companies. It lacks support; most senators think it’s too “radical.” But some version of a hidden pool may be a crucial alternative to a public option if the Democrats are serious about “keeping insurance companies honest.”

Is it the only option? Of course not. The point is that these ideas fall near the bottom of the “monolithic” scale, and the German, Dutch and Swiss examples show how Europeans have achieved one freedom unknown to ordinary American workers in the current age of employer-based public health: The power to choose a plan independent of a job, to take it with them if they quit and to change it whenever they please.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.