By the time Congress got around to ratifying the Declaration of Independence on August 2nd, 1776, it was already old news.

On that day, an enlarged parchment copy of the document — adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4th — appeared at Independence Hall in Philadelphia for its official signing. Some delegates present that hot afternoon in August refused to sign; several of the 56 congressional delegates who eventually did weren’t even present on that historic July day. Their signatures would one day complete the treasured manifesto that now sits in the National Archives, a historic object made whole by their ink.*

Few colonists would have recognized August 2nd as a milestone. By then the Declaration had already been re-printed in 29 major provincial newspapers, a magazine, and on hundreds of broadsides (poster-like announcement sheets) passed from hand to hand and home to home.

“When we think about the news of independence, we have to recognize the importance of this viral spread throughout the colonies,” says R. Scott Stephenson, chief curator at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

The Declaration drew great interest, but was not treated with the breathless reverence that we afford the document today. “Americans didn’t file past and pay reverence like they do today,” Stephenson says.

Instead, most people were exposed to the text through newspapers and broadsides, or by hearing it read aloud. And the timeline of how the Declaration of Independence went viral encapsulates the haphazard way in which America learned its Great Experiment had begun.

July 2nd, 1776:

Gathered at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, members of Congress voted to declare the United States independent from Great Britain in a resolution put forward by Richard Henry Lee:

Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

After a brief moment of celebration, Congress then turned its attention to an early version of the Declaration of Independence drafted by the “Committee of Five”: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. “As far as they were concerned, the Declaration was simply just an explanation of their vote for independence, which is why Adams thought everyone would celebrate the nation’s birth on July 2nd,” Stephenson says. “It just took until the 4th to adopt a document that officially explains the action they had taken.”

The first public news of the historic vote came from a last-minute addition to that day’s edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, the thrice-weekly newspaper published by printer Benjamin Towne since 1774. The paper contains possibly the first and best buried lede in American journalistic history. Hastily inserted under the minutes from various provincial committees, we find the first news of independence: “This day the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States.”

This wouldn’t be Towne’s only claim to fame. According to the Library of Congress, Towne’s allegiances shifted throughout the Revolutionary War, and he was eventually branded a turncoat and traitor. With the Post shedding advertisers and readers, he turned the paper into the first daily in the U.S. — a single pitiful sheet of paper. The Post died in 1784.

July 3rd, 1776:

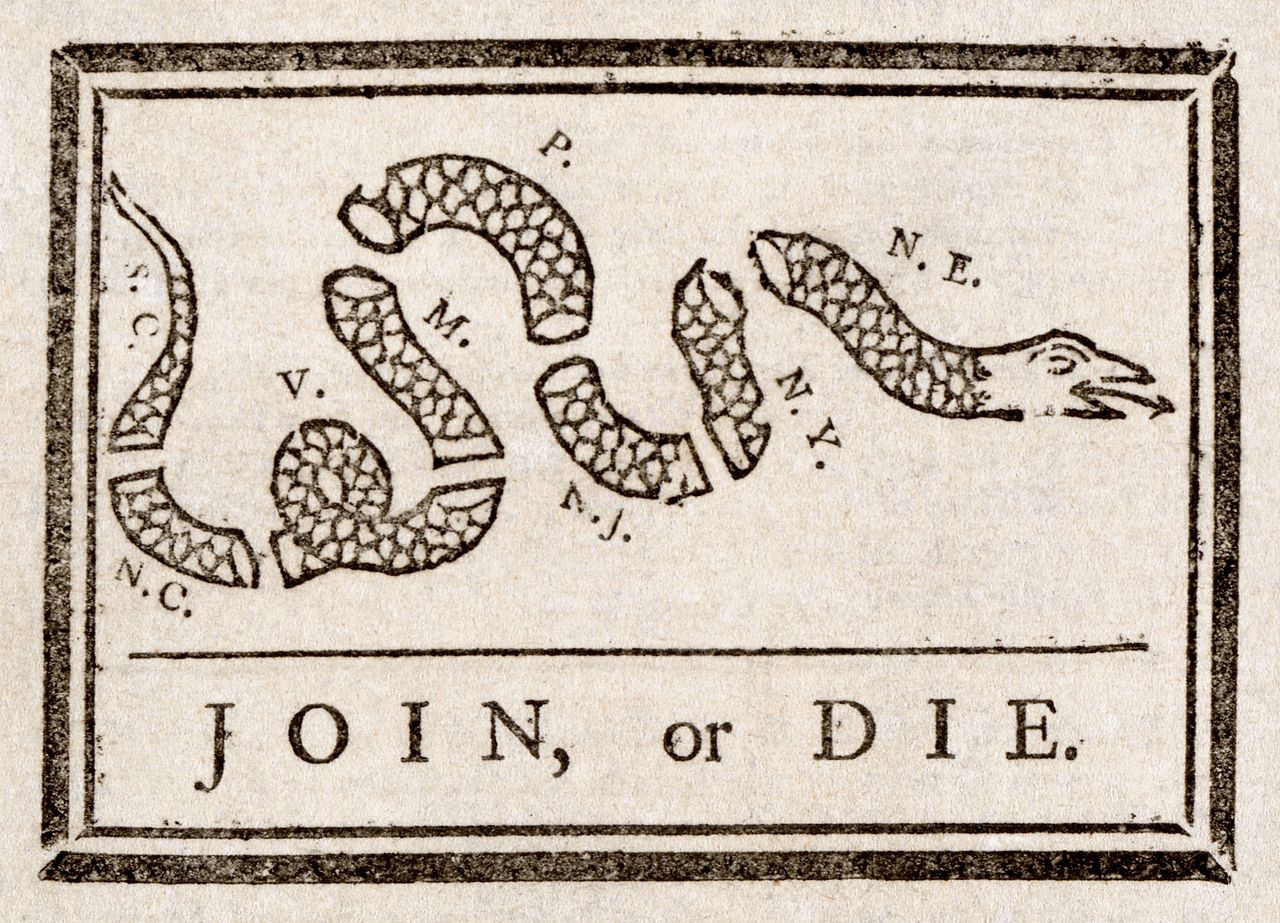

While the Post owned the night, the Pennsylvania Gazette — then the most successful newspaper in colonial America — won the morning by announcing Congress’ historic vote from the previous day. The paper had previously printed the first political cartoon in U.S. history, Join or Die, by Benjamin Franklin, the infamous broken snake that would become a symbol of colonial independence during the conflict with Great Britain.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

July 4th, 1776:

Editing complete, the wording of the Declaration of Independence was formally approved by Congress.*

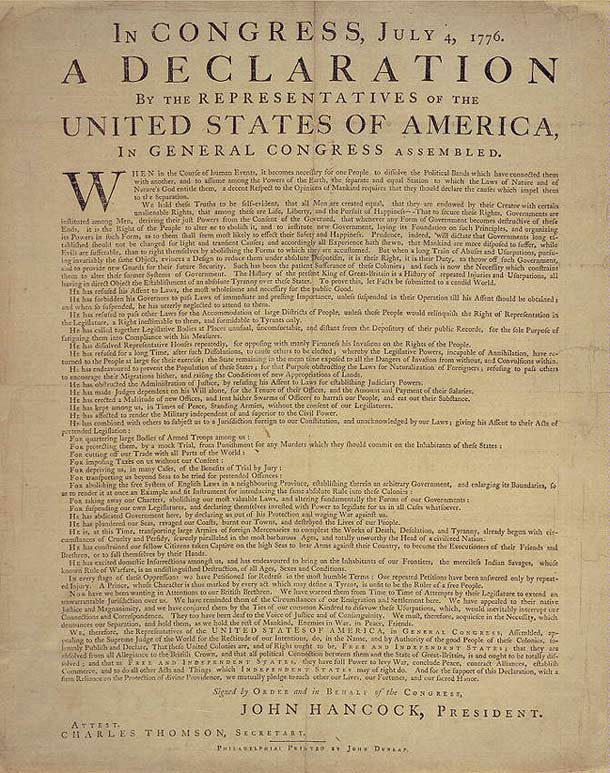

The first copies of the Declaration were produced late that evening by John Dunlap, a printer who’d secured a contract with the Continental Congress. John Hancock ordered Dunlap to print 200 broadsides to be distributed to state legislatures and read aloud to Continental soldiers on distant battlefields throughout the colonies. These were official documents, dispatched by Jefferson to every provincial governor and every Continental commander in the field, although a few were posted outside state houses in the coming days.

Despite his historic role in distributing the Declaration, Dunlap ran afoul of the revolution. He would lose his lucrative contract with Congress in 1779 after accidentally revealing French aid to American forces by printing a revealing letter from Thomas Paine in the Journals of the Continental Congress.

Printed late at night, the Dunlap broadsides didn’t immediately make their way to the local papers. The July 4th edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, despite its quick work on July 2nd and the paper’s subsequent record of publishing historical documents from the Revolution, contains no reference to the Declaration. Chances are simply that the Post, relying on a printing press not that much nimbler than Gutenberg’s, had already been set by the time the copy arrived.**

July 5th-6th, 1776:

While the Dunlap broadsides were en route via horseback to every provincial government in the colonies, Philadelphia’s English-language papers were getting scooped — in German.

Under editor Heinrich Miller, a colleague of Dunlap’s and a fearsome advocate for colonial rights since 1762, the Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote was the first newspaper to officially announce the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 5th:

Yesterday the honorable Continental Congress declared the United Colonies free and independent states. The declaration is now in press in English; it is dated July 4, 1776, and will be published today or tomorrow.

According to the Museum of the Revolutionary War, German printers Melchior Steiner and Charles Cist published early public broadsides containing the text of the Declaration the next morning, on July 6th, displaying them in front of their print shop.

The Declaration would appear for the first time in English in full on the front page of the Pennsylvania Evening Post on the evening of the 6th, hours after the Steiner and Cist version hit the streets of Philadelphia. Miller would publish a slightly different German translation in Staatsbote in paper’s next issue on July 9th.

July 8th, 1776:

The first official public reading of the Declaration of Independence was conducted by Colonel John Nixon after the Liberty Bell summoned the citizens of Philadelphia to Independence Hall, the bell’s most famous tolling before it was spirited away from the advancing British army in the fall of 1777.

Here’s how the Philadelphia and New York Gazettes reported its reception, per Harper’s 1892 classic “How the Declaration Was Received in the Old Thirteen”:

(Photo: Library of Congress)

This day the Committee of Safety and the Committee of Inspection went in procession to the State House, where the Declaration of Independency of the United States of America was read to a very large number of the inhabitants of this City and County, which was received with general applause and heart-felt satisfaction; and in the evening our late King’s Coat of Arms was brought from the Hall in the State House, where the said King’s Courts were formerly held, and burnet amidst the acclamations of a crowd of spectators.

According to Harper’s, the Declaration was also read aloud for the first time in the nearby towns of Trenton, New Jersey, and Easton, Pennsylvania, where it received “acclamations” from assembled taxpayers and was celebrated with Continental military parades in the streets. The full text of the Declaration appeared in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, one of the first successful dailies in the country.

July 9th, 1776:

Along with other colonial governors and commanding officers in the field, Hancockhad dispatched one of the Dunlap broadsides to General George Washington, then commander of Continental forces in New York, with instructions to proclaim independence “at the Head of the Army in the way you shall think it most proper.”

With hundreds of British naval vessels looming in the city’s harbor, Washington instructed various brigade commanders to recite the Declaration to their troops “in a clear and audible voice” at dusk that evening. Washington himself read the document aloud in front of City Hall, inciting a riot where hundreds of soldiers tore down a towering statue of George III. The statue was eventually vandalized to make some 42,000 musket balls for Continental forces fighting under Washington’s command.

But Washington wasn’t very pleased with the symbolic destruction of the British tyrant. “He may have been secretly smiling, but this was a lapse in discipline among his troops,” Stephenson says. “He came down hard on them.”

While soldiers were rioting in New York, theDeclaration had spread to Baltimore with a full-text appearance in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, a sister publication to the eponymous Pennsylvania Packet.

July 10th, 1776:

As Dunlap’s broadsides begin to circulate through the colonies, major newspapers began reprinting the Declaration in full ahead of local government minutes, including Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Gazette and Pennsylvania Journal and New York’s Constitutional Gazette.

Most notably, Mary Katherine Goddard, one of 30 female printers in the colonies at the time, published the Declaration on the front pages of The Maryland Journal and The Baltimore Journal. In January 1777, she would print another broadside based on the engrossed copy of the Declaration bearing the signatures of 55 signers (one wouldn’t sign until later in the war); this copy would eventually end up in the National Archives, and represents the first time the American public learned exactly who their Founding Fathers were.

According to the Library of Congress, Goddard went on from her lucrative printing business to become the first woman in the nascent American states to serve as postmaster, but was forced to resign after 14 years due to “prejudices at this time against women making a profit.”

July 11th, 1776 -August 2nd, 1776:

The Declaration began to appear on front pages across New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. With Continental forces recently withdrawn from Boston, the document wouldn’t appear on the front pages of local papers there until July 18th, when it graced the front pages of the city’s Continental Journal and New England Chronicle, although many residents had learned of the Declaration through the Dunlap broadsides.

On the day the official, engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence was finally signed and authorized by the Continental Congress, the document made its last known front-page appearance in the immediate aftermath of its adoption, this time in the South Carolina & American General Gazette.

August 10th, 1776:

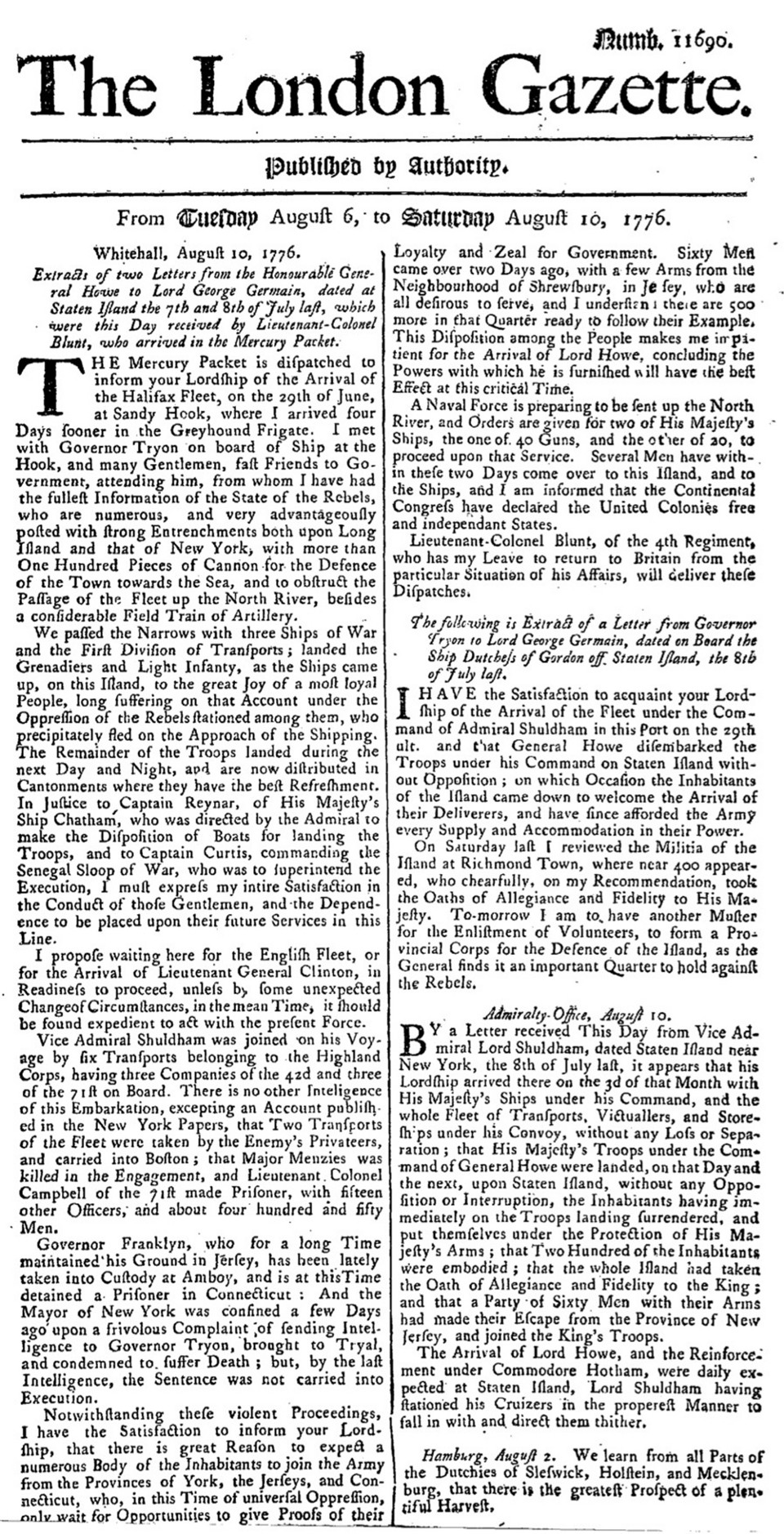

Not until the second week of August did news of colonies’ formal renunciation of the crown reach Great Britain. According to Todd Andrlik, the first official word of the American uprising arrived in London buried in a personal letter from General William Howe to Lord George German, packed away on a packet ship (a postal ship designed to carry correspondence to between British colonies) out of Staten Island on July 7th.

It was a Crown mouthpiece, The London Gazette, that first broke the news in England, and in an amusingly modern form: a “16-word, 106-character, Twitter-esque extract from a Howe letter,” as Andrlik puts it, nestled in the August 10th edition of the paper: “I am informed that the Continental Congress have declared the United Colonies free and independent States.”

The Gazette scooped the London Evening-Post, which played catch-up with a short blurb: “Advice is received that the Congress resolved upon independence the 4th of July; and have declared war against Great Britain in form.”

August 16th, 1776:

Historians do not agree among themselves on when, precisely, the complete text of the Declaration first appeared in European media. Some say that King George himself was scooped by a paper in Northern Ireland. In August 1776, the BelfastNews-Letter allegedly gained access to the first copy of the Declaration of Independence bound for London, after the ship carrying it “ran into heavy storms off the north coast of Ireland and was forced to seek refuge in the port of Londonderry.”

The News-Letter claimed that, while the Declaration was eventually carried by horse to Belfast for another ship to rush it to King George, an editor managed to gain access to the document and print the complete text on the front page of the August 23–27 edition.

The Journal of the American Revolution disputes this claim. According to Andrlik’s research at the British Library in London, the Declaration first appeared in full in two papers, the Public Advertiser and Lloyd’s Evening Post and British Chronicle, on August 16th, 1776, scooping other British newspapers by mere hours. Andrlik claims the Declaration would appear in Edinburgh on August 20th, Dublin on August 22nd, and Frankfurt on August 23rd.

But to Stephenson, it’s not the timing of the News-Letter’s Declaration that’s most intriguing. “It’s printed on paper that had a tax stamp on it,” he notes, a reference to the Stamp Act that so incensed the revolutionaries in the first place. “It’s ironic that this is printed on paper used for the very act that sparked the Revolution.”

America’s allies in the revolutionary French government were meant to receive the full text of the Declaration before any other European organization through a copy sent on July 8th to Silas Deane, an American agent in Paris, by Congress’ Committee of Secret Correspondence. But, according to a letter sent from Deane postmarked for August (and received in November), the package, along with instructions to translate, publish, and distribute the document in the French media never arrived.

Not that it mattered: By the time Deane and Congress realized the mistake, the Declaration was already circulating in every major European newspaper on the continent. In just two months, the American declaration of freedom had spread to almost every English-speaking country on the planet, proving that the spread of a powerful idea depends on the power of the idea more than on the sophistication of its delivery system.

*Update—June 28, 2016: This article initially misstated the timing of Hancock’s signature and the printing of the Dunlap broadsides.

**Update —June 28, 2016: This post has been updated to better reflect the timing of the Dunlap printing.