Every election is followed by an effort to make sense of its results. This effort is pretty natural, and probably necessary, for political observers and for candidates and parties trying to figure out the best way forward, especially after a loss. But what is the consequence of going with one interpretation over another?

I examined this using a survey experiment, and I wrote up the results for a paper that I’ll be presenting this week at the annual convention of the American Political Science Association. Basically, I was interested in knowing whether the argument that Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 presidential race due to “identity politics” changed voters’ perceptions of the 2020 election. That is, I was curious if that argument caused voters to desire different sorts of candidates and a repositioning of the Democratic Party.

I conducted a survey using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk among a group of 803 participants, roughly half of whom were self-described Democrats or Democratic-leaning Independents. Half of the respondents saw the following message near the beginning of the survey:

According to some political experts, Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election because she focused too much on identity politics. She appealed directly to African Americans, Latinos, gays and lesbians, and women voters whenever she spoke, but she never painted a broader picture of American life or addressed basic issues like jobs and health care that are of concern to all Americans.

Other respondents (the control condition) were shown a brief message about the use of painkillers in the treatment of children.

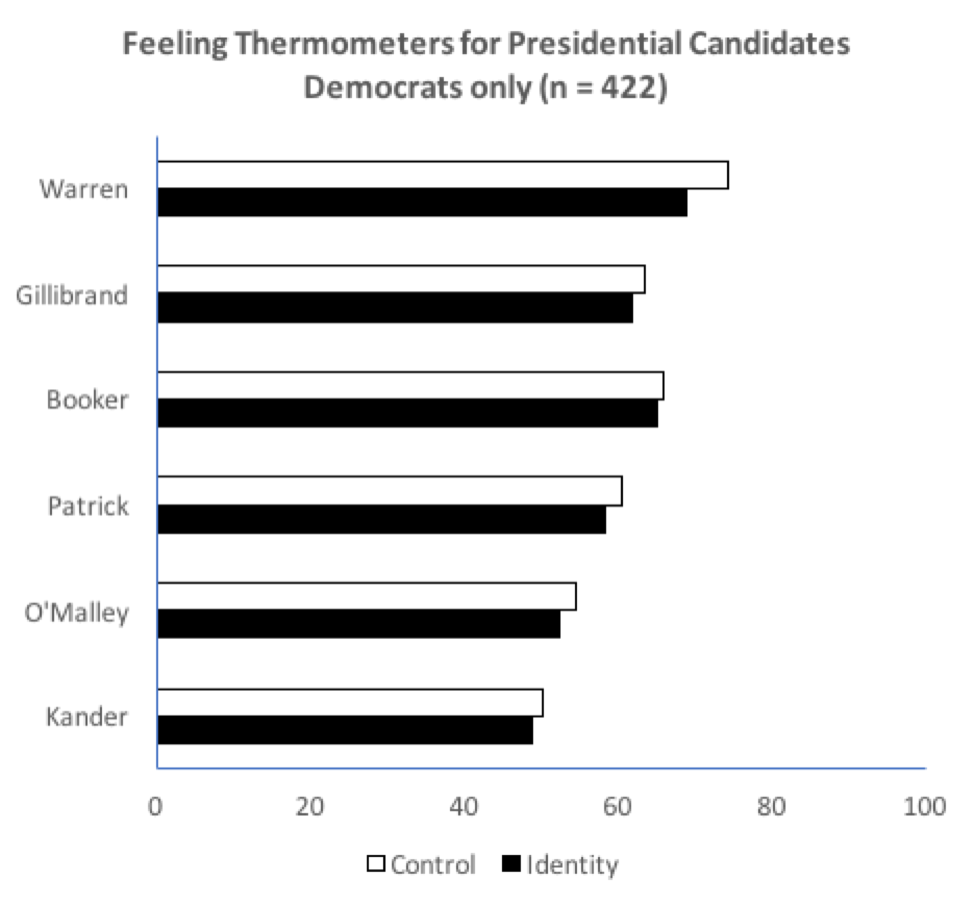

I then asked respondents to evaluate six possible Democratic candidates for president, rating them on a “feeling thermometer” scale. Those candidates were Jason Kander, Martin O’Malley, Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, Cory Booker, Deval Patrick. I included the titles of the candidates and a photo of each. Notably, this candidate pool consisted of two white men, two white women, and two African-American men.

As the chart to the left shows, respondents who saw the identity politics language gave all six candidates lower thermometer scores than those in the control condition did. In only one case did this reach statistical significance: Respondents who saw the identity politics language gave Warren about a five-point lower thermometer evaluation than those who didn’t. This effect is slightly larger when the sample is limited to Democrats.

My impression is that the identity politics cue makes respondents less comfortable with the idea of Democrats nominating someone other than a white male in 2020. Why this effect is only large enough to be statistically significant in Warren’s case isn’t entirely obvious. She’s different from the other candidates mentioned in that she enjoys much greater name recognition. She’s also much more closely tied to feminism and liberalism in the public mind. So it’s not surprising that she would suffer as respondents became less comfortable with left-wing politics, but it is surprising that people’s opinions on her moved so much given that they had more fixed views about her than about the other candidates.

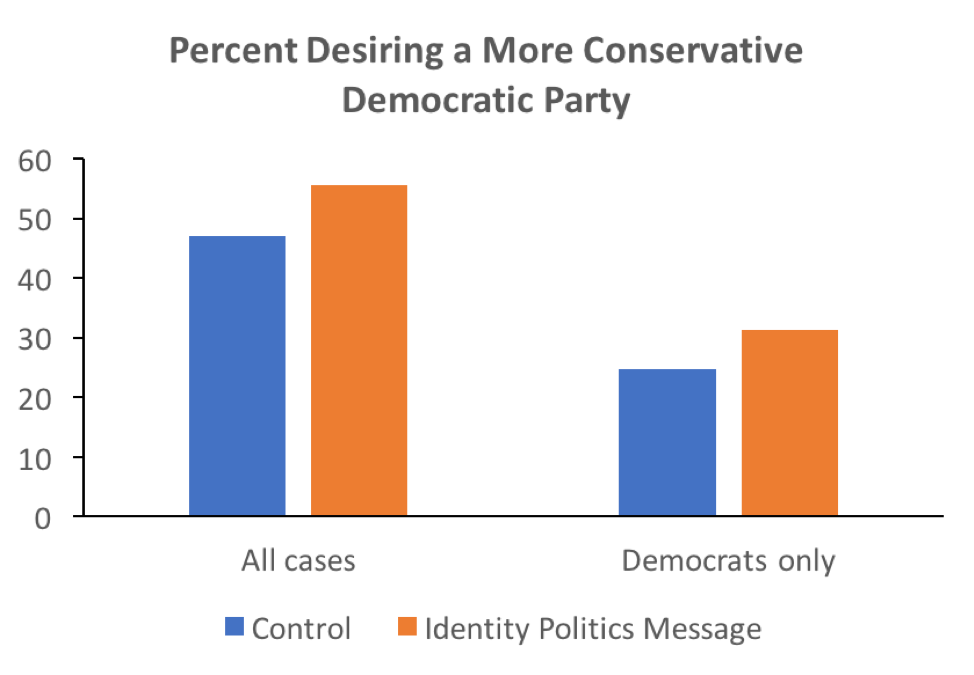

I also asked respondents to place the Democratic Party ideologically on a scale from zero to 10, with 10 being the most conservative position, and then asked them to say where they think the Democratic Party should be. If their number on the second question was higher than their number on the first, then they wanted the party to become more conservative.

Seeing the identity politics message made respondents about 7 to 8 percent more likely to want Democrats to move rightward. This was true for Democrats as well as for the sample as a whole:

There evidence here isn’t overwhelming. The effects are fairly modest, but they do suggest an impact, however temporary, of the kind of interpretation political observers and party leaders offer after elections. The identity politics argument seems to have some effect on making Democrats, and voters in general, want a more conservative Democratic Party, and possibly advantages the white male candidates pursuing the presidency. How Democrats understand the last election, it seems, determines how the party prepares for the next one.