The recent police shootings represent perhaps the most significant political obstacle to the Black Lives Matter movement yet.

By Jared Keller

A police officer attends a candlelight vigil for Baton Rouge Police Officer Matthew Gerald on July 18, 2016, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. (Photo: Joshua Lott/Getty Images)

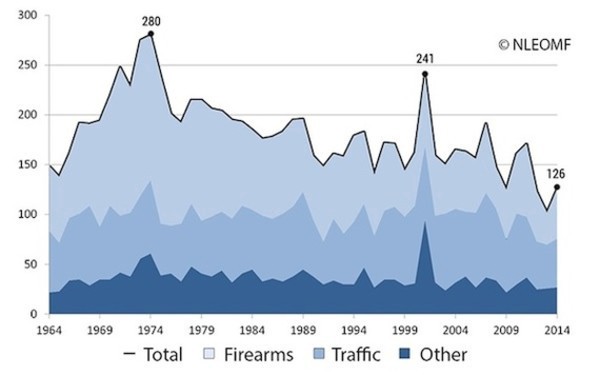

Years of data suggest that it’s never been safer to be a police officer in America. Statistics compiled by the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund (NLEOM) in 2014 show that law enforcement deaths have declined sharply since the early 1970s, from 280 in 1974 to 126 in 2014. Accordingly, police officer fatalities per million Americans have plummeted since 1900, according to historical data compiled by the Foundation for Economic Education; the only major spikes occurred during Prohibition, the Reagan-era “War on Drugs,” and following the September 11th attacks.

(Chart: National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial)

While Federal Bureau of Investigation data indicates the number of police “feloniously” killed jumped from 27 officers in 2013 to 51 in 2014, that’s still far below the average for officer deaths since the crime wave of the 1980s, as the chart to the left, courtesy of the NLEOM, shows. The war on cops was, it seemed, largely a myth.

But what if it wasn’t? What if that stark increase in 2013 wasn’t a fluke, but a harbinger for violence on the horizon? The last few weeks have seen a horrific series of attacks on members of law enforcement. In Dallas, sniper Micah Xavier Johnson shot and killed five officers during protests against the recent police shootings of two African-American men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. Less than two weeks later, Missouri native and veteran Gavin Long, who had posted often on the Internet about “fighting back” against white police officers, killed three police officers and wounded three more in Baton Rouge, itself the site of intense protests against the shootings of Sterling and Castile. The Baton Rouge tragedy came mere days after several men were arrested over an alleged plot to kill a Louisiana police officer.

These police shootings, all of them carried out by disturbed men — Johnson had been discharged from the military amid sexual harassment allegations, and medical experts say Long appeared similarly unhinged in his YouTube videos — offer the most significant political obstacle to the Black Lives Matter movement yet. Forget political obsolescence on the state and federal level: The police are considered sacrosanct in the United States, and their murder could all but doom the necessary push for reform to the political grave.

This isn’t simply because of rhetoric against the police like that deployed by Long: America built a police force beyond reproach. It started in 1964, when Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater vowed in his 1964 Republican presidential nomination acceptance speech to “[enforce] law and order” and combat “violence in the streets.” With crime rates in the U.S. exploding between the 1960s and ’80s, and with the skyrocketing murder rate dominating the headlines, Americans demanded more aggressive policing, carried out by more police, who were better armed.

Americans are perpetually convinced that crime is on the rise, despite the fact that the crime rate has declined steadily over the last 25 years.

The people got their wish — the Pentagon gave more than half a billion dollars in military equipment per year to increasingly militarized police forces in 2014 — and the crime rate fell. It’s no wonder that, despite confidence in police dropping to its lowest level since 1993 following the recent spate of shootings of African-American men, law enforcement remains one of the most trusted institutions in American civic life.

But thanks to the role of police in beating back the crime wave of the 1980s, the mantra of “law and order” has become political doctrine — and, as a result, Americans are perpetually convinced that crime is on the rise, despite the fact that the crime rate has declined steadily over the last 25 years. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and, unfortunately, incidents like those in Dallas and Baton Rouge only rejuvenate this tired, false belief.

The deaths of those eight officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge over the last three weeks is a tragedy of immense proportions, and the alleged radical motivations of Johnson and Long have caused concern that tensions between African-American communities and the police have hit a violent boiling point. But the worst possible consequence of this tragedy is that the conversation around police reform and how law enforcement can better engage and serve minority communities will come to an end.

We are living in era where black Americans are more likely to be the targets of excessive force by police, more likely to end up in prison, more likely to die in a county jail, more likely to be convicted by all-white juries (and more likely to end up facing all-white juries in the first place), and more likely to face a shakedown over small fines they can’t afford. Rooting out the very real issues of racial inequality in the American justice system and keeping police officers safe is not a zero-sum game, and conflating the war on cops with the Black Lives Matter movement treats it as such.

America is already safe, but it’s up to us to keep it that way.

||