Every complex political campaign in every democratic election boils down to two simple strategies: Pray that more people show up to vote for you, or make sure that the other candidate’s supporters stay home. President-elect Donald Trump’s stunning upset can likely be attributed to the latter.

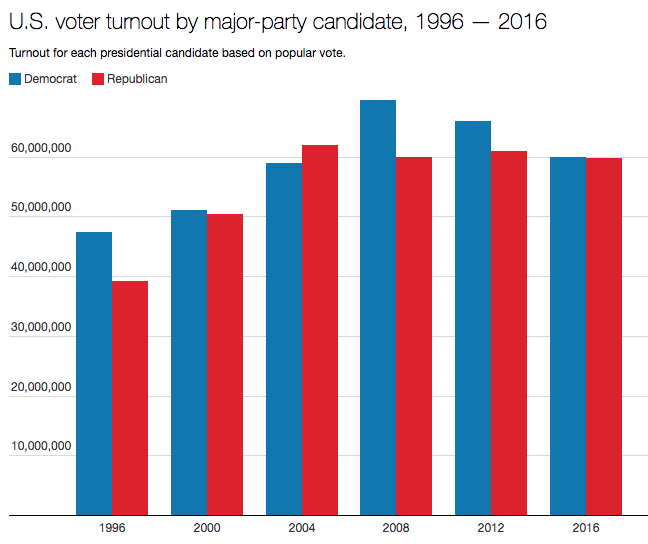

Of more than 231 million eligible voters in the United States, 49.6 percent simply didn’t vote on November 8th, the worst turnout in a presidential election since the 1996 contest between President Bill Clinton and Republican Senator Bob Dole (the lowest turnout in history with 49 percent of voters abstaining, according to the U.S. Election Project). Of voters who did show up, 25.6 percent voted for Hillary Clinton while another 25.5 percent voted for Trump, resulting in a popular vote victory for Clinton despite an electoral loss. Trump’s razor-thin 1 percent victory in the crucial swing states can be sliced a thousand different ways, but there’s a simpler explanation on a national level: Decisions are made by those who show up, and Democrats failed to do just that.

OK, that’s not totally true. As the discrepancies between the popular and electoral vote in 2000 and 2016 remind us, decisions are really made by the Electoral College (hence the emphasis on swing states). But the drop-off in Democratic turnout between the election of Barack Obama in 2008 and Trump’s 2016 triumph is astounding.

Republican turnout hasn’t risen to a fever pitch since 2004, in spite of Trump’s concerted appeals to working-class white voters and other groups ostensibly left behind by the demographic and technological progress of post-9/11 America. The resurgence of America’s white Christian identity played a part, but the reality is that Clinton saw major declines in enthusiasm compared to Obama’s 2012 coalition, according to The Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein. Democrats sealed their own fate from the comfort of their living rooms.

For liberals discombobulated by Trump’s upset, an easy complaint centers on voter suppression, the most under-covered phenomenon of the 2016 cycle. As I wrote in October, some 11 percent of eligible voters (around 21 million people) don’t have government-issued photo identification, and the voter ID laws in force in 36 states as of Election Day would have disproportionately affected minority voters who likely would have gone for Clinton. And remember that, back in 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated part of the Voting Rights Act, opening the floodgates for the largest swell in voter suppression in 50 years. At the same time, there’s as of yet little evidence that these new measures changed the course of the election, as the University of California–Irvine political scientist Rick Hasen observed.

“If you look at the states without strict voter ID laws, Democratic turnout was way down anyway,” Hasen tells Pacific Standard. “I’m not in a position to say whether it was the [Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James] Comey letter or the quality of the Clinton candidacy, but it’s very difficult to say that the main culprit here was strict voter ID when you see turnout way down in places like Pennsylvania and Michigan that didn’t make its voter ID laws any stricter.”

In the 2016 campaign cycle, Hasen says that voter ID laws would likely have had more of an impact on down-ballot races like the North Carolina gubernatorial contest. “Right now, Roy Cooper is locked in a battle with Governor Pat McCrory, and that could shift with the counting of provisional ballots,” Hasen says. “Most state voter ID laws were put on hold by the courts, but there were still some changes that might be contested.”

“Still,” he adds, “Democrats who are looking to voter suppression as a scapegoat for this loss should look elsewhere.”

But what about voter suppression at the ballot box itself? Trump’s late campaign call on supporters to monitor polling places for signs of widespread voter fraud (itself a dangerous and false accusation) by “other communities” sparked anxiety over potential intimidation of those same minority communities targeted by voter ID laws.

Indeed, Mother Jonesrecorded dozens of instances of polling place snafus and outright suppression in the days before the election, and a special election-rights hotline set up by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law (or “Election Protection”) reportedly received more than 4,000 complaints during early voting, which marks an uptick from previous elections.

“Keep in mind, voter intimidation of African-American voters has been a regular feature in the South since the Voting Rights Act,” Hasen warns. “Everyone is looking for intimidation, but nothing’s been found on a large scale.”

Trump’s calls for vigilante poll watchers may eventually bear the brand of outright, coordinated voter suppression. His mid-October call to action put the Republican National Committee in legal jeopardy: Democrats alleged that Trump’s call to action violated a 1982 so-called court-ordered “consent decree” that forbid the RNC from “engaging in ballot-security measures” like patrolling polling stations. Should proof of such a violation emerge, the consent decree might be extended to 2025. Such an extension would implicitly tie voter intimidation to the Trump campaign.

The remaining question here is whether the judge in the case is going to extend the “consent decree” for another eight years, Hasen suspects it’s unlikely. “The question is whether Trump is an agent of the RNC and engaging in these activities in a way that would be illegal if done by the RNC. In the ruling from last week, the judge did not view Trump as such,” he says, suggesting that the Republican establishment’s late-campaign attempts to distance itself from Trump may award the president-elect innocence by technicality. “This may get challenged on appeal if that process continues, but the core question is whether the agency derives from Trump as an agent of the RNC for purposes of ballot security, or a broader question of being an agent throughout the campaign, the latter of which is unlikely.”

Time will also tell if this uptick in polling place-based intimidation significantly tilted the course of the 2016 election. Election Protection expected more than 175,000 voter intimidation complaints by the time the polls closed on Election Day, “roughly equal” to 2012 levels, according to U.S. News and World Report.

All of this suggests a more compelling explanation for 2016’s dismal Democratic showing: Instead of blocking the polls, Trump killed Democrats’ will to even show up. Even though so many Americans are iffy on Trump—an Election Day exit poll showed that a majority of Americans consider their new president-elect “not qualified” for the office — the Republican nominee successfully managed to paint Clinton as the avatar of the political and business elites in Washington, counting on harnessing broader anti-establishment anger against the former secretary of state to literally depress potential Clinton voters.

And yes, this was a concerted strategy: In the weeks before the election, Bloomberg Businessweek’s Joshua Green and Sasha Issenberg revealed that the Trump campaign’s massive direct marketing operation, built on the candidate’s own quixotic free-media binge, was focusing not on building up the Republican nominee, but on tearing down Clinton. From their story:

Trump’s campaign has devised another strategy, which, not surprisingly, is negative. Instead of expanding the electorate, Bannon and his team are trying to shrink it. “We have three major voter suppression operations under way,” says a senior official. They’re aimed at three groups Clinton needs to win overwhelmingly: idealistic white liberals, young women, and African Americans. Trump’s invocation at the debate of Clinton’s WikiLeaks e-mails and support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership was designed to turn off Sanders supporters. The parade of women who say they were sexually assaulted by Bill Clinton and harassed or threatened by Hillary is meant to undermine her appeal to young women. And her 1996 suggestion that some African American males are “super predators” is the basis of a below-the-radar effort to discourage infrequent black voters from showing up at the polls — particularly in Florida.

The Trump campaign focused on voter depression, not voter suppression, working to make sure idealistic liberals already worried about Clinton wouldn’t even bother voting. And it worked: Clinton, already a historically weak candidate, suffered as much from the late, bizarre resurgence of her email saga. Consider a Gallup survey of 30,000 Americans that found people most associated Clinton with “email,” “lie,” and “scandal” (“Though Clinton has attacked Trump on several issues related to his character, no specific words representing negative traits have ‘stuck’ to Trump the way the word ‘email’ has to Clinton,” per Gallup).

A Morning Consult poll found that the vast majority of Republican voters didn’t really care about the October sexual assault tape that establishment politicos and the media (myself included) thought might sink Trump’s campaign. With the Democratic establishment’s standard-bearer already bloodied from a long primary fight against Bernie Sanders, the Trump campaign simply took a page from their candidate and went nasty and negative. And it worked: While Republicans turned out for Trump, Democrats sat at home and moped.