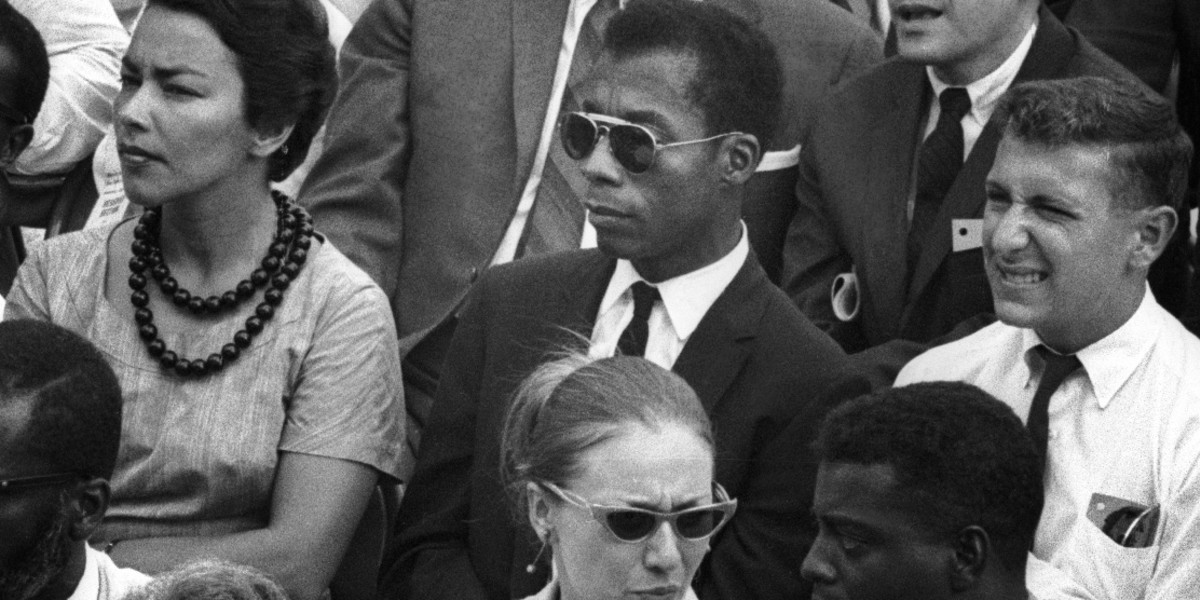

I Am Not Your Negro, Raoul Peck’s Academy Award-nominated documentary, is an evocative and moving exploration of the power of James Baldwin’s writing, but it’s also a barometer of how far we think we’ve come with reconciling America’s messy racial politics.

Narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, Peck’s movie is structured around a reading of Remember This House, a manuscript that Baldwin left unfinished upon his death in 1987. Baldwin’s task for this book was ambitious: to tell the story of America through the lives of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X — black men killed while trying to save their country.

Baldwin’s words come with a mandate — for blacks, in particular — to carve out a new kind of history.

In Baldwin’s own famous words: “The history of America is the history of the Negro in America. And it’s not a pretty picture.” Peck spends an hour and a half illustrating this monstrous history, crosshatching Baldwin’s notes for his text with haunting period footage, including a 15-year-old Dorothy Counts integrating a North Carolina high school, and taped interviews with Baldwin himself. If the film feels a bit unfocused, that might be the point: It crisscrosses past and present, indicating how the systems of abuse that Baldwin chronicled have persisted. Peck also splices pivotal scenes from the present — including the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, and demonstrations for the Black Lives Matter movement — into the movie, such that it’d be easy to say that Baldwin is newly relevant, even in this “enlightened” year of 2017. But to say that would be to get it exactly backward — Baldwin never stopped being relevant, and his augury was never truly debatable. To think so is to simplify and distort a man who, certainly to blacks at least, never stopped demanding that our country reckon with our presence.

Peck knows this. He knows that, especially in white minds, Baldwin’s words have been archived but dismissed, set aside to make room for more evolved concerns in some mythic post-racial society. He knows that to ignore Baldwin is to ignore history and the possibility of taking on — let alone taking down — the resurgence of demagoguery and naked white supremacy that we see today. Peck knows all of this, and I Am Not Your Negro is his attempt to strip away any delusions that viewers may have about what it means to be black in America. “I’m terrified,” Baldwin says, “by the moral apathy — the death of the heart — which is happening in my country.” We need only look at the White House to see that the past, of course, is never past, and that these words echo with exhausting familiarity.

In an interview with Slate’s Aisha Harris, Peck talks about how it took him the better part of a decade to produce the movie, and why Baldwin is timeless rather than timely: “I never wanted to be ‘current’ in the sense that I follow the news, follow the historical moment of the day. It was always, for me, to go back to the fundamentals.” Peck continues, pointing out how “Baldwin had already written [these] words 40, 50 years ago, and we should ask ourselves, ‘How come they are so pertinent, so right?’”

About 15 minutes into the movie, we see Baldwin sparring with conservative commentator William F. Buckley in a debate at Cambridge University in 1965. The question at hand is this: “Has the American Dream been achieved at the expense of the American Negro?” To no one’s surprise, the debating society deems Baldwin the winner. Baldwin’s performance is mesmerizing, and I recommend that you watch it in full. At one point during the exchange, he states to the crowd of very white British students that “it comes as a great shock to discover the country — which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity — has not in its whole system of reality evolved a place for you.” It’s also maddening, though, to see a genius have to entertain the thought that American prosperity has been built on anything other than non-white bodies. But there Baldwin was, pushing back against all of that. “I am stating very seriously, and this is not an overstatement,” he says. “I picked the cotton, I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip — for nothing.”

Baldwin’s sparring match with Buckley reminds me of a similar debate that took place at Oxford University when I was a graduate student there. The proposition before the audience was whether present-day America is institutionally racist. A friend of mine told me later that she’d felt compelled to leave the event early—even before a string of cartoonish right-wing pundits, including a Breitbart News contributor, could tee up to speak — because she found it absurd and dispiriting that, in 2015, people could still think of the persistent legacy of slavery as a topic to be intellectualized rather than as an evident evil that we’ve yet to fix.

And that’s precisely it. The force of Peck’s film — with its devastating juxtaposition of archival and contemporary footage of police violence and protests — is that it doesn’t allow viewers to take solace in aspirational illusions about the virtues of the present. Peck confronts us with the truth that, while Baldwin didn’t live to see our current political reality, he absolutely saw it coming. Indeed, it’s impossible to spend as much time with Baldwin as we do in I Am Not Your Negro without also feeling prodded to return to his books, to reread his criticism of America as a blueprint for today. With Baldwin, we’re able to take history, hold it up to the light of the present, and glimpse what ultimately shines through. Much of what’s there is startling. Even so, Peck shows us, Baldwin’s words don’t demoralize; they galvanize, and, in a sense, they come with a mandate — for blacks, in particular — to carve out and achieve a new kind of history.

“How, precisely, are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation here?” Baldwin asks in a clip from a 1963 television segment, said to have “seared the conscience.” “And how are you going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here?”