How do the Faroese maintain their ancient Nordic fishing industry? By running an impressive 21st-century operation. Currently enjoying a salmon boom, the Faroe Islands are using smart-grid technology to stay green — and to protect their fisheries.

By Sarah Witman

Saken, Streymoy, Faroe Islands. (Photo: Stig Nygaard/Flickr)

This week, Pacific Standard

looks at the global seafood industry — how it’s responding to class, consumer trends, and a new climate.

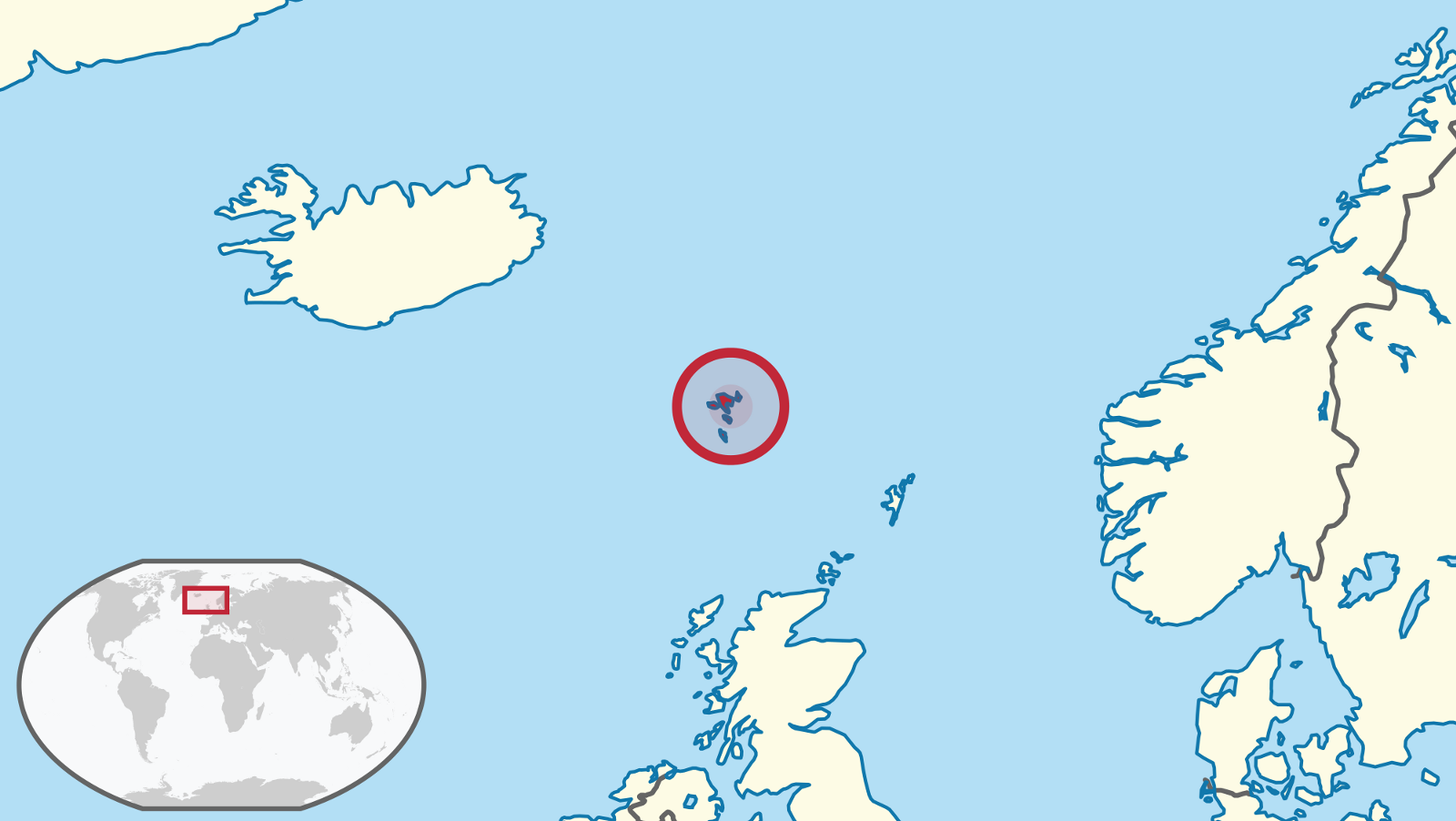

Halfway between Iceland and Norway lies a small, seabound nation: the Faroe Islands. From above, the T-shaped chain of islands is a barely perceptible birthmark on the northernmost waters of the Atlantic Ocean, on the brink of the Norwegian Sea.

Up close, the archipelago is composed of mossy green plateaus atop towering crags that drop sharply toward the waves below. These rugged basalt formations, relics of the islands’ volcanic origins, are streaked with strata: compacted layers of vegetative and volcaniclastic sediment. Gentle slopes and valleys in the coastal lowlands are dotted with houses and flocks of sheep. At the water’s edge, sailboats and fishing vessels — many of them sporting the tall, dramatic keel of a Viking longboat — dock along ever-active harbors.

Map of the Faroe Islands. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Fishing is by far the largest industry in the Faroes, accounting for more than 95 percent of exports and half the nation’s gross domestic product. While not every one of the Faroes’ 50,000-some residents works in the industry (even remote Nordic islands need bankers and podiatrists), they all know someone who does.

“Pretty much everyone [in the Faroes] is descended from fishing people,” says Quentin Bates, a British journalist (and former fisherman) who covers Faroese business. “It’s absolutely central to the whole culture.”

In what is thought to be the first written account of the Faroe islands, a voyaging Irish abbot called Saint Brendan said he and his brethren “saw great streams of water flowing from many fountains, full of all kinds of fish.”

Perhaps by nature of its small population and isolated locale, Faroese culture is highly individualistic. The country has its own language — a derivative of Old Norse, most similar to Icelandic — and, despite being part of the Kingdom of Denmark, is self-governed. It’s a renegade in terms of fishing, too: In the 1990s, the Faroes abandoned Iceland’s lucrative fish-quota system after less than a year and established its own unique Faraoese system — one based in part on quotas (limiting the number of fish you can catch) and in part on days spent at sea (regardless of how many fish are caught). The Faroes’ quotas and days-on-sea regulations vary depending on the species of fish.

While this maverick’s mentality is not always popular with other nations, especially those that must share its marine resources — namely Iceland, Norway, and coastal Europe — it has helped the Faroese fishing industry to flourish.

In what is thought to be the first written account of the islands, a voyaging Irish abbot called Saint Brendan said he and his brethren “saw great streams of water flowing from many fountains, full of all kinds of fish.”

Icelandic and Faroese women washing fish inEskifjörður, Iceland, circa 1900. (Photo: Cornell University Library)

That cornucopia of fish (for which Brendan tearfully praised God, according to his journal) lives on to this day. The fish population in the Faroes is remarkably diverse and abundant, thanks to a warm jet from the Gulf Stream that flows straight into the clean, icy waters surrounding the islands and provides the perfect environment for fish habitation.

The most profitable species are groundfish, such as cod and haddock; farm-raised salmon, often swimming in massive open-water cages of 120 to 130 feet in diameter; shrimp and various species of prawn; and pelagic, a term for fish breeds that avoid both the sea-bottom and shore; these include herring, blue whiting, and mackerel.

With its natural bounty of fish, coupled with historically low fuel prices (one of the biggest costs in commercial fishing is diesel fuel) and high global demand, the Faroese fishing business is booming. Pelagic fisheries in particular are having a moment, especially mackerel. Major infrastructural projects — extending part of the harbor near the capital city of Tórshavn, opening up a new transit route to transport freights of fish to other countries, expanding the largest fish-storage refrigerator in the region, and a number of other construction projects — are cropping up across the isles.

“Everything is in fishing’s favor at the moment, but it’s an extremely cyclical business. If things are good now they wont be next week or next year.”

“They’re having quite the bonanza,” as Bates puts it.

By far the biggest windfall was driven by geopolitical strife, and has taken place over the past two years. When the United States and other Western countries responded to Russia’s violent seizure of Crimea (a small, self-governing European territory, not unlike the Faroes) with sanctions in August 2014, Russia banned all food imports from Australia, Canada, the European Union, Norway, and the U.S.

The ban did not, however, apply to the autonomous Faroes, essentially giving the island’s fishing industry a monopoly in Russia.

“While the European Union is suffering from the Russian boycott, Faroese fishermen will capture the Russian market,” as the Danish newspaper Berlingskereported last August.

Russia was already one of the Faroes’ top consumers of salmon, but, after the self-imposed embargo, the country began importing nearly all of its salmon (and paying 25 percent more for it than any other country) from the Faroes, along with various other types of fish. The Faroes’ total fish exports in the first half of 2015 grew 12 percent compared with the same time period the previous year, before the embargo started.

A recent salmon shortage in Chile, caused by fish deaths due to algal blooms and red tide, as well as labor protests among Chilean fishermen, might increase the demand for Faroese exports even further.

For centuries, the Faraoese have documented their history through sagas — sung epics like those of their Norse ancestors — and if ever a saga were written about the modern-day fishing industry in the Faroes, its climax would hit right about now, with the islands’ unlikely dominance of the fish trade.

Sheep of the Faroe Islands. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

But this streak of good fortune won’t last forever, as every good fisherman knows.

“Everything is in fishing’s favor at the moment,” Bates says, “but it’s an extremely cyclical business. If things are good now they wont be next week or next year.”

Market values and costs can plummet as surely as they can skyrocket, and politics are equally unpredictable. As recently as 2013, the European Union imposed sanctions on herring and mackerel imports after the Faroe Islands blatantly disregarded international quotas on those species. While the dispute was eventually settled, it was something of a wake-up call for the Faroese on how vulnerable their primary industry can be.

“We learned the hard way that we had to access other markets,” Niels Winther, an adviser to the Faroese Fish Producers Association, toldthe Arctic Journal.

“The level of government is so close to what’s happening on ground; there aren’t huge layers of bureaucracy in between industry and state.”

There are, of course, natural fluctuations as well: Short-term cycles within long-term cycles related to mating, food availability, water temperature, and other factors can be impossible to predict. A well-known natural cycle in the northern Atlantic Ocean, called Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, involves a shift between warmer and cooler sea-surface temperatures about every 20 to 40 years. Although the resulting difference in temperature is less than one degree Fahrenheit, it affects weather and climate in North America and Europe (including the Faroes) — and, in turn, fish stocks. Global climate change introduces an even greater degree of flux, though its effects are harder to pinpoint with precision.

One saving grace is that not every sector of fishing fluctuates at the same rate —groundfish fisheries, for example, seem to experience changes over a shorter period of time than do pelagic fisheries. So there is some semblance of balance in which the Faroese can take comfort.

Perhaps more important, the steely, cohesive identity of the Faroese may help them weather economic storms. The nation has historically operated with a community-oriented ethic, whether it’s sharing the meat from an island-wide whale hunt or governmental support of industry needs.

“The level of government is so close to what’s happening on ground; there aren’t huge layers of bureaucracy in between industry and state,” Bates says. “It’s been like that forever.”

Embodying this idea on a grand scale, three major companies within the Faroese fishing industry have teamed up with the federal government and a group of utility companies to help bring the entire country a stabler, cleaner energy supply.

The project, called Power Hub, was implemented in 2012 to combat rampant power outages — and occasionally full-on blackouts — across the islands.

Disconnected from a mainland power supply, subject to extreme and unexpected weather (imagine what the wind causing this waterfall to flow backwards would do to a power line), and partially reliant on intermittent energy sources (mostly wind), the country is highly susceptible to energy outages.

“The Faroes has one of the world’s most challenging power systems,” says Anders Birke, lead information technology architect for Dong Energy, which designed the Power Hub system.

In the event of a power failure or disruption, Power Hub’s centralized network of computers will automatically (in less than a second) cut off power to the Faroes’ top three energy users — Hiddenfjord salmon farm, Bergfrost cold storage site, and Kollafjord Pelagic fish-processing facility — stabilizing power across the rest of the grid.

The companies have agreed to this system, despite the temporary power outages, as it helps prevent longer-lasting outages for everyone in the Faroes. Plus, it affects their industry — Hiddenfjord relies on electric-powered pumps to supply oxygen to holding tanks, for example; without power, fish will die, costing the company millions.

While the Faroe Islands is Lilliputian compared to U.S. cities that are considering similar smart-grid systems — including New York and San Diego — it provides a useful model for others to emulate.

“We see ourselves as a live laboratory, where new and innovative solutions could be developed and tested in a small but full-scale environment,” said Hákun Djurhuus, CEO of Faroese energy company SEV, in a statement.

The added stability from the Power Hub, and other smart measures, is especially important for the Faroe Islands as it increases its use of cost-saving, eco-friendly, and locally abundant renewable energy sources (wind power, hydropower, and perhaps, one day, tidal power) which are inconsistent and can be trickier to harness. The Faroese government has set a goal of becoming 75 percent renewable-energy dependent by 2020, and 100 percent by 2030 — lofty ambitions, to be sure, but more than 50 percent of the nation’s electricity already comes from renewable sources, up from 40 percent in 2010.

This far out, it’s difficult to predict how this saga will unfold. But history tells us this tiny fishing nation can weather the storm.

||