Elections are generally considered the key to representative democracy. Voters may grow tired of them, but elections nonetheless serve a valuable purpose: a chance to hold politicians accountable for their actions. If we don’t like the way they’ve behaved in office, we can kick them out and find someone new. The very threat that that might happen is supposed to make politicians behave better.

This is a situation where parties, rather than individual candidates, really need to take up the slack. The incentives for any individual to mount the electoral equivalent of a suicide mission just aren’t great.

This whole theory falls apart if politicians run unopposed. A one-candidate election is essentially no election at all. Of course, this doesn’t happen much for higher offices; even very popular presidents still draw challengers. Senators and governors are rarely given a free ride. But go a bit further down the ballot and you may be surprised by how little competition there really is.

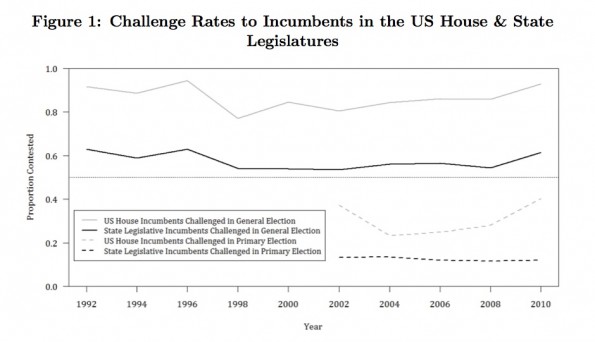

In a forthcoming paper from Legislative Politics Quarterly (draft here), Steve Rogers examines just how often United States House incumbents and state legislative incumbents are challenged. As the chart below shows, typically 80 to 90 percent of House incumbents are challenged each election. That’s pretty respectable, although it still means that 50 or so House seats go uncontested each election. But the real story is in state legislatures, where usually fewer than 60 percent of incumbents are challenged. Almost half of state legislators across the country face no challenger at all.

Why might this be? Well, for one thing, quite a few districts just aren’t very competitive. You can blame gerrymandering or voter sorting or anything you want, but in many districts, it’s very obvious which party is going to win. Which means that in order for a seat to be contested, the out-party has to find some poor sap who is willing to put her life on hold for six months, tap all of her friends and family for money, and submit to media scrutiny, all for a race she’s 99 percent likely to lose.

It’s vitally important to field lots of candidates even in seats where that party has little shot at winning. It gives the party the chance to take advantage of changes in the political environment or colossal errors by the other party.

Sure, there are some perks to running a losing race: It can generate some press, maybe helping out your business, and it can endear you to some people in your party for the prospects of a future office. Also, you never know what might happen. There could be a scandal or a big shift in the political climate and you might find yourself in office. But at the state legislative level, that’s usually not enough of a payoff to counter the down sides. Most of those posts pay less than $30,000 a year, and most voters still won’t be able to pick you out of a line-up. Plus, you’ll probably lose the seat in the next election.

This is a situation where parties, rather than individual candidates, really need to take up the slack. The incentives for any individual to mount the electoral equivalent of a suicide mission just aren’t great. For a party, however, it’s vitally important to field lots of candidates even in seats where that party has little shot at winning. It gives the party the chance to take advantage of changes in the political environment or colossal errors by the other party. It also keeps the other party in check—they’re less likely to govern in an extreme manner if they’re more confident people will run against them.

In the summer of 2010, the Democratic challenger to Governor Dave Heineman (R) in Nebraska withdrew due to a scandal, and it briefly looked like there would be no Democratic challenger in that race at all. At that point, political scientist Larry Sabato gave an interview excoriating the Nebraska Democratic Party, saying:

[Democrats not finding a candidate] would display such weakness. And really, for a group that receives special privileges under the law because they provide Americans a choice, it would be a dereliction of duty.

He was, of course, completely right. Fielding candidates in unfavorable districts might seem like a waste of precious resources to a party—and most of the time, it is—but it’s also a responsibility. Arguably, it’s the most important responsibility parties have.