China’s controversial anti-corruption campaign continues onward—not just at home, but also in the United States and around the globe.

Beijing’s efforts to return escaped criminals from abroad is ostensibly aimed at rooting out the corruption hindering the nation’s growth and roiling its citizens. But rights activists advise international governments against cooperating with Chinese law enforcement, saying China’s anti-graft campaign is simply a thinly veiled bid to bring back home political dissidents escaping persecution.

Chinese President Xi Jinping opened the International Police Organization (Interpol) general assembly in Beijing on Tuesday to hundreds of participants from 156 countries, including the U.S. Also on Tuesday, China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency reported that Interpol, the global police cooperation agency, is collaborating with Chinese authorities in over 3,000 investigations around the world each year. Last year, China issued 612 “red notices”—alerts seeking the extradition of accused criminals abroad—leading to 17 extraditions.

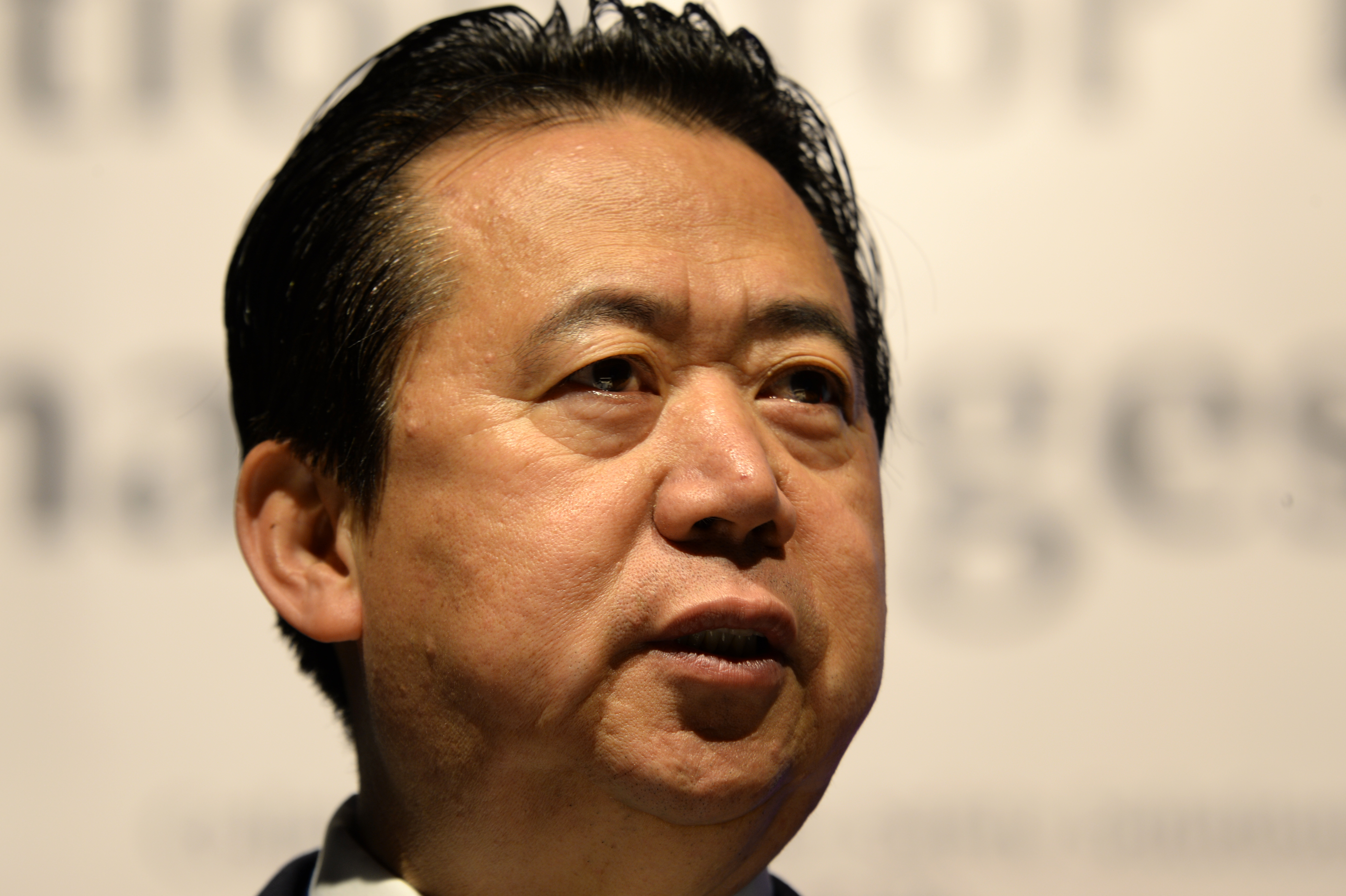

Just one day before Xi’s speech, international advocacy group Human Rights Watch issued a statement calling on Interpol to address what it charges is China’s abuse of the red notice system. HRW’s statement expressed concerns about Interpol’s respect for human rights, especially with Chinese Vice Minister for Public Security Meng Hongwei now helming the organization.

“China has already shown a propensity for using Interpol to its own ends, sometimes in violation of Interpol’s principles and practices,” HRW’s China director, Sophie Richardson, tells Pacific Standard. “Now that China has a top slot in the organization, it is imperative that Interpol address past—and prevent future—abuses.”

HRW’s statement on Monday pointed to numerous occasions in which Beijing has issued red notices for high-profile political dissidents challenging its rule. Over a decade ago, China issued a red notice against Dolkun Isa, a Germany-based advocate for the rights of China’s beleaguered ethnic Uyghurs. In the U.S., China has issued a red notice against Wang Zaigang, who has advocated for democracy in the People’s Republic. Authorities in their current countries of residence have not acted on the red notices in either case, but traveling abroad with a red notice comes with great uncertainty.

“China has already shown a propensity for using Interpol to its own ends, sometimes in violation of Interpol’s principles and practices.”

Neither Interpol nor the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., responded to requests for comment.

China’s use of Interpol red notices should concern all Americans—not just Chinese nationals escaping their homeland’s authorities—Richardson argues. “Nobody should be subjected to the kinds of ill treatment Chinese police are know to mete out, inside or outside China,” she says. “That the scope of that force’s reach is growing is an ominous sign for all of us.”

Rights advocates like Richardson claim Beijing is using its red cards to return escaped critics; Meng, meanwhile, called for international collaboration at the Interpol general assembly on Tuesday.

“Cooperation is embedded in the genes of the organization, just as neutrality is its lifeline,” Meng said. “We must hold dear the cooperative and neutral spirit in the same way as we cherish our lives.”

In recent years, Beijing has demanded greater cooperation from American enforcement officials in its attempts to repatriate wanted Chinese nationals living in the U.S. There is no extradition treaty between the two countries, so the degree to which Washington cooperates shifts with the constant flux of Sino-U.S. relations.

It remains unclear to what extent the Trump administration is presently cooperating or will cooperate with the bid. What is clear is that the Trump administration has cooperated at least once in the past. In June, Washington extradited a Chinese national surnamed Zhu, wanted for “violation of personal rights,” according to a Chinese Public Security Ministry press release reported by Reuters. Zhu had overstayed his visa in the U.S.

(Photo: Roslan Rahman/AFP/Getty Images)

In April, China issued a red notice against Chinese billionaire and political dissident Guo Wengui, Reuters reported. Guo remains in New York.

The Trump administration is not the first to cooperate with Chinese authorities on law enforcement. As early as September of 2015, the administration of President Barack Obama returned Yang Jinjun, a Chinese national wanted for charges of bribery, as a result of bilateral talks with China.

Though HRW’s Richardson says it’s unclear to what extent the U.S. is cooperating with Interpol, she is nonetheless “concerned that U.S. law enforcement may not be aware of intimidation in the U.S. by Chinese officials of people from China, and that the U.S. may not be fully taking into account the well-founded fears returnees may have of torture or ill-treatment.”

Asked to clarify the degree to which the Trump administration is cooperating with Chinese authorities, Department of State staff directed Pacific Standard to the Department of Justice, which did not respond to multiple email requests for comment.

While the Trump administration’s exact role in China’s hunt for what it calls criminals remains unknown, Beijing’s most wanted individuals appear, oddly enough, to be voluntarily returning to China from the U.S.

Xu Xuewei, a technology entrepreneur from the eastern province of Jiangsu, went back to China from the U.S. to turn himself in to authorities, Reuters reported Sunday. So too did driving school headmaster Liu Changkai earlier this month. The reasons for their return to China were not immediately evident. Xu returned “under the influence of policy and legal deterrence,” Reuters reported, and Liu cited loneliness as the reason for his return.

The role—if any—that the U.S. played in the events that led to Xu and Liu’s return was not mentioned. Apparently Liu’s loneliness in the U.S. was such that even a Chinese prison seemed more appealing.