In Ecuador, an impoverished woman plans to sell 335 grams of a drug she cannot even identify. She’s caught. Her sentence? Eight years in prison. In Mexico, a woman finds heroin planted in her suitcase. Her punishment? Twenty-two years behind bars. In Bolivia, a man stomps coca, the first step in the process to make cocaine. His penalty? Ten years.

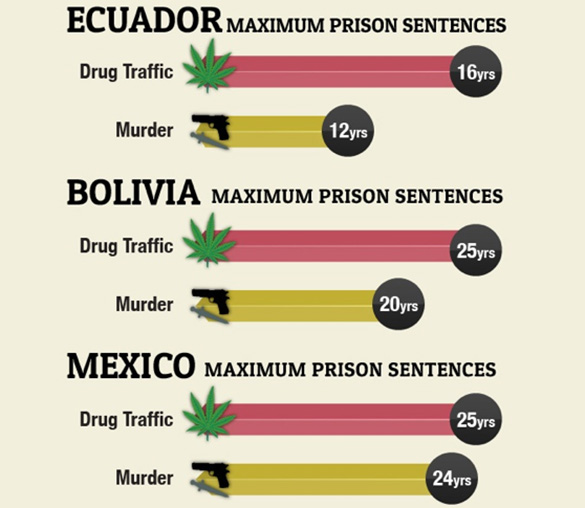

Mexico, Bolivia, and Ecuador are nations where the minimum and maximum penaltiesfor drug traffickers are longer than those given to murderers.

For years, Latin American governments have been dishing out increasingly harsh punishments to people convicted of drug-related crimes, including those convicted of low-level offenses—possession of, say, 50 grams of marijuana. While anecdotal evidence has often pointed toward this pattern, a new studyconducted by Dejusticia, a Colombian research and advocacy group, documents this trend and comes to a harsh conclusion: “In three of the seven countries surveyed, drug trafficking garnered longer maximum and minimum penalties than murder.” In all countries studied, “the maximum penalty for drug trafficking is nearly equal to or, in most cases, greater than the maximum for rape.”

“That, for me, was the most shocking data that we found,” explains Rodrigo Uprimny, the director of Dejusticia and one of the study’s authors. Uprimny and his two co-authors found that many countries make no distinction between “very, very small drug traffickers” and those selling “hundreds of kilos of cocaine.” From the report: “In a few cases, a small-scale marihuana [sic] dealer is punished as if he were Pablo Escobar.”

The study analyzes drug crime laws in seven places—Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico—and highlights two trends.

First: Researchers document a sizable increase in the number of drug-related conducts criminalized. Fifty years ago, governments in these seven countries used just 67 descriptive verbs to describe a drug-related crime. Today, that number is 344.

Second: The study shows a dramatic increase in the length of mandated minimum and maximum prison terms for drug-related conducts. In all seven countries, the average maximum sentence for a drug offense increased from 34 years in prison in 1950 to 141 years today. Peru is the country with the most marked upward trend; in less than 60 years, the highest minimum (yes, minimum) penalty for a drug crime increased from two to 25 years.

Mexico, Bolivia, and Ecuador are the nations where the minimum and maximum penaltiesfor drug traffickers are longer than those given to murderers.

(GRAPH: THE WASHINGTON OFFICE ON LATIN AMERICA)

The study does not address whether these policies had any benefits in curtailing drug crime. But the report’s authors conclude with an urgent call for reform.

Governments “should favor harm-reduction policies over punitive policies,” they write. “The weak links in the drug chain must receive government protection rather than excessive punishment, and the possible harm associated with psychoactive substances should be minimized through an approach based on public health and alternative development, not criminal punishment and the use of force.”

This tough-on-drug-crime approach, says Uprimny, originated in the north. Latin American countries, he says, have a tradition of shorter, lighter sentences. But as punishments for drug crime in the United States became harsher, so too, did those in Latin America. “It’s politically very useful for politicians,” says Uprimny. “You can win votes saying that you’re going to get tough on drugs. You are seen by the population as a person that is really interested in protecting kids and teenagers, even if the concrete effect might be the opposite one.”

What does he mean?

Analia Silva is the Ecuadorian woman imprisoned in 2003 after authorities caught her with an unidentified drug she had planned to sell. She is a single mother. “Eight years of being without your children,” she says, speaking in a video produced by the Transnational Institute and the Washington Office on Latin America, “and eight years for them without me. Because when they sentenced me—and it’s the same for every woman they sentence—they do not only sentence the person who committed the crime, they also sentence their family, they also sentence their children.”

“They want to get rid of crime,” Silva continues, “but they are the ones promoting it. If my children are left alone, what can they do? Go and steal. My daughter becomes a prostitute, my son a drug addict, a drug dealer.”

There are small signs of movement away from a punitive approach to drug crime, both in the United States and in Latin America. In 2006, while Silva was in prison, Ecuador reviewed its drug policies, declared them unjust, then pardoned about 2,000 people convicted of offenses, including Silva.

In end the end, she served about five years.

Other countries, like Argentina and Colombia,have decriminalized the possession of small amounts of drugs. (The amount and the type of drug varies from place to place.) Still others are working to do so. (Often, though, the amount decriminalized is so nominal that users and low-level sellers are still arrested for possessing a substance.)

“These are not dramatic changes, but are important changes,” says Uprimny. “In the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, the very punitive U.S.A. approach had terrible consequences on establishing, in Latin America, a very punitive approach. Maybe now we could have the contrary story. That some reforms in the United States might support some reforms in Latin America. And visa versa.”

“But that’s a hope,” he continued, “more than an academic analysis.”