It may be nearly 80 years old, but for many Americans Reefer Madness is still terrifying.

Before it became a cult classic, the 1936 anti-drug propaganda flick stands as one of the biggest morality tales in the history of cinema. In the film, all-American high school students Bill Harper and Jimmy Lane have their lives ruined by a single doobie, descending into a mad spiral of murder, attempted rape, and insanity, all in the throes of marijuana addiction. The film’s message and rhetoric remain at the core of moral arguments against marijuana legalization to this day. (The anti-pot argument is best captured by the shrill pleas of Simpsons character Helen Lovejoy: “Won’t someone please think of the children!”)

As it turns out, the kids are going to be all right: According to a new comprehensive analysis, legalizing medical marijuana does not result in a corresponding increase in consumption among teens.

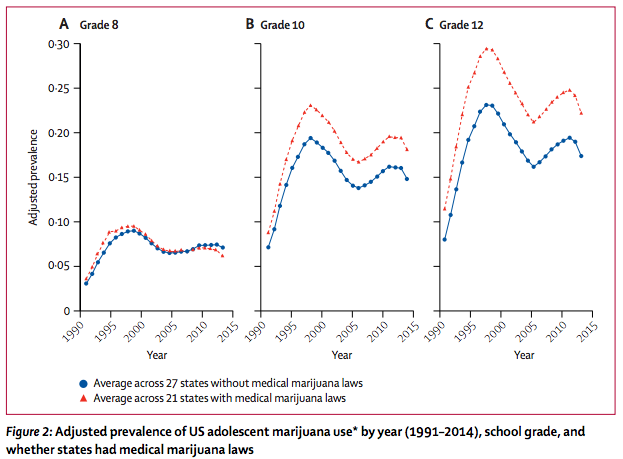

The study, conducted by researchers at the Columbia University Medical Center and published in the Lancet, covers 24 years of surveys on drug and alcohol consumption and included more than one million adolescent Americans in eighth, 10th, and 12th grade across 48 states. While the researchers found that overall marijuana consumption grew in states that passed medical marijuana laws before 2014, there was no significantly disproportionate uptick in consumption among young people.

Legalizing medical marijuana does not result in a corresponding increase in consumption among teens.

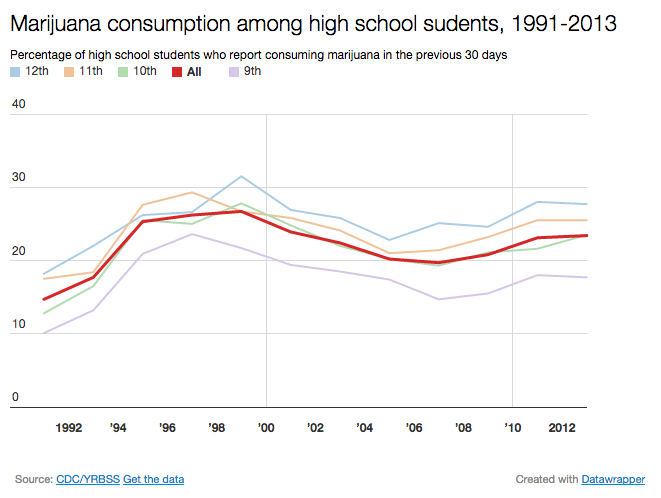

The Lancet study confirms recent research published in the Journal of Adolescent Health last year, which examined 20 years of data on some 11 million American students from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. While some 21 percent of students reported using marijuana at some point in the previous 30 days, the researchers found that “there were no statistically significant differences in marijuana use before and after policy change for any state pairing.” In fact, despite a significant rise in usage in the early 1990s, marijuana consumption has remained relatively stable among teens.

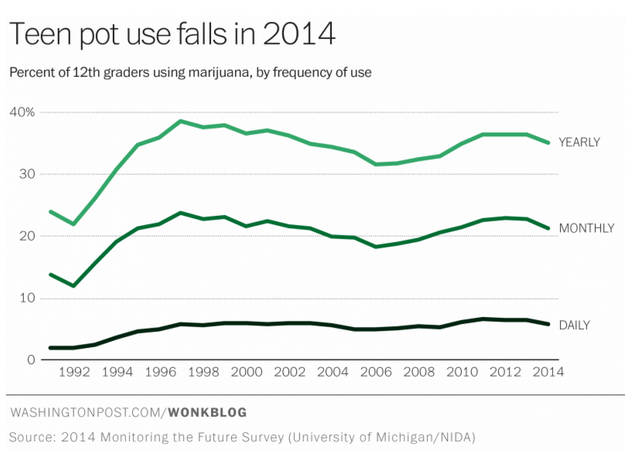

But what about states like Colorado and Washington, which have legalized marijuana for recreational, rather than medical, consumption? Data from the Monitoring the Future survey—the same data source used in the Lancet study—actually shows a gradual decline in consumption among eighth, 10th, and 12th graders in those states. This chart from the Washington Post shows that teen pot use among 12th grades in particular fell in 2014, despite rising in full-on legalization across the country:

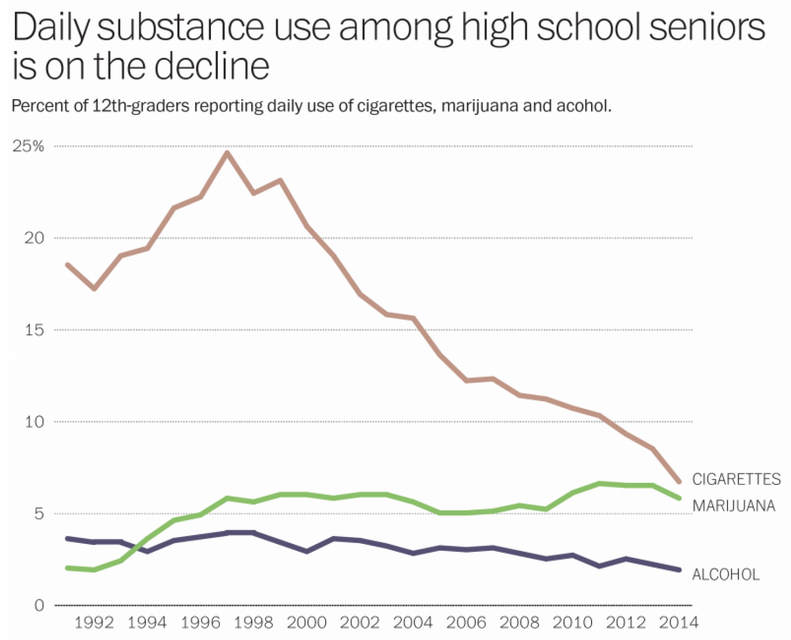

Why is this happening? As it turns out, today’s teens are sort of square compared to their hard-partying parents. The same study that showed a decline in marijuana consumption in 2014 also found a sharp drop in overall substance abuse, including alcohol and cigarettes, among today’s high-schoolers. In fact, marijuana is the only substance to show a significant uptick in consumption over the past 20 years—which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, considering that weed is way, way safer than both alcohol and cigarettes.

This preponderance of data pokes a hole in a central argument against legalization as old as the Nixon administration, which says that relaxing regulations on marijuana will “send the wrong message” to America’s youth and lead to an explosion of usage among teens. But with cigarette and alcohol use at their lowest point since the National Institute on Drug Abuse began collecting data in 1975, and marijuana use statistically unaffected by legalization, it looks like the moral scaremongering of Reefer Madness may remain just that: madness.