A new report points out that many private, not-for-profit colleges have abysmal graduation and loan re-payment rates.

By Dwyer Gunn

Donald Trump holds a media conference announcing the establishment of Trump University on May 23, 2005, in New York City. (Photo: Thos Robinson/Getty Images)

Over the last several months, a lawsuit in California filed by former students of Trump University, Donald Trump’s now-defunct for-profit real estate school, has attracted quite a bit of media attention. In the latest installment of the saga, a number of newly released documents detail the school’s questionable tactics — former employees state that students were encouraged to open up credit cards they couldn’t afford in order to pay tuition, and some were even told that Trump himself would play an active role in their education. One former Trump University employee described the school as “a façade, a total lie.”

For-profit schools like Trump University have been under the microscopein recent years, and with good reason: Many of them employ dodgy recruiting practices, and the schools’ students (who are usually low-income, disadvantaged) frequently leave with lots of debt and unimproved career prospects. A working paper released last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that associate’s and bachelor’s degree seekers at for-profit schools saw a decline in post-attendance earnings, relative to pre-attendance earnings. Master’s degree seekers fared slightly better, but vocational certificate students did not. “Among certificate students, we find that for-profit students experience lower earnings effects than their public sector counterparts, a result that holds even after accounting for differences in student demographics and programs of study using inverse probability weights,” the authors concluded.

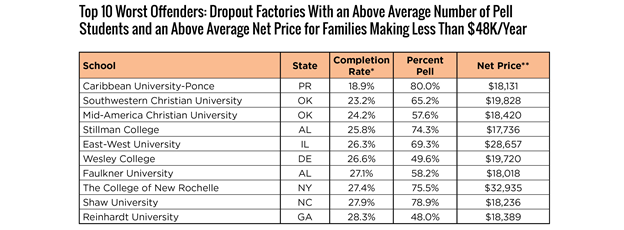

But a new report from the Third Way, a centrist think tank, points out that it’s not just for-profit colleges that are failing low-income students. Private, not-for-profit schools are afflicted by many of the same ills. The average four-year, private, not-for-profit school graduates only 55 percent of those freshman who enter with federal loans (within six years). The graduation rates at some schools are particularly egregious — at 50 schools, less than 25 percent of students graduate. The table below, from Third Way, lists the worst offenders.

*Completion rate is for loan-holding students.

**Net Price refers to average net cost for students with incomes <$48,000. (Chart: Third Way)

Even students who graduate from many of these schools end up with low earnings and later struggle to re-pay their student loans. Only 63 percent of loan-holding graduates of private, not-for-profit schools earned more than $25,000 six years after graduation, and 15 percent of graduates fall behind on their student loan payments within three years of graduation.

Low-income students face a particularly difficult reality: In general, schools with high percentages of Pell-eligible students exhibit lower graduation rates, lower earnings, and lower re-payment rates, while “high-performing” schools educate far lower percentages of Pell-eligible students. In other words, the schools that are the most likely to graduate students who go on to earn a good salary and pay back their student loans are the same schools that don’t accept very many low-income students.

While some of this may be the result of high admissions standards and a dearth of qualified, low-income applicants, it’s not the whole story, according to Third Way:

These schools have the capacity to take in more Pell students, but in recent years, many have chosen to increase the amount of merit pay they disburse at the expense of need-based aid — ostensibly to lure “top talent” to their schools. Similar findings were recently highlighted in a report by the U.S. Department of Education, which found that it is often admissions policies at highly-selective schools that favor wealthier students due to an emphasis on things like extracurricular activities and “legacies” (familial relationships with alumni). Schools that have a proven track record of success with Pell students have a responsibility to take in a greater share of students who could benefit from those outcomes the most. The Department of Education cites research that have found that “highly-selective schools could increase the representation of low-income students by 30% without compromising SAT or ACT standards.”

So what’s a low-income student to do? The report highlights a number of schools that are successfully educating low-income students without saddling them with unreasonable debt loads. For example, three schools — Baptist Memorial College of Health Sciences, Jefferson College of Health Sciences, and Cardinal Stritch University — educate lots of low-income students (over 38 percent of the student body is Pell-eligible) and also rank in the top decile with respect to graduate earnings.

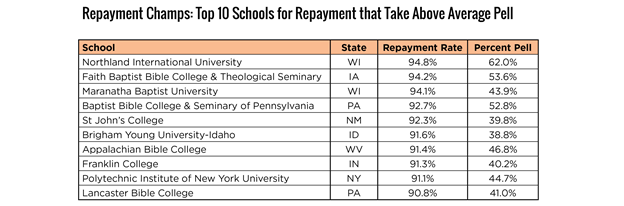

The table below lists schools with both high loan re-payment rates and high percentages of low-income students:

(Chart: Third Way)

There are, of course, steps that policymakers could take to help private, not-for-profit schools better serve low-income students. Colleges with high loan delinquency rates, for example, could be forced to cover part of the costs of those delinquencies, a consequence which might incentivize them to better prepare students for post-college realities. Schools with low graduation rates could be required to develop and implement plans to improve those rates. Meanwhile, high-performing schools could be encouraged to take on more low-income students, while those schools that do successfully serve low-income students could be rewarded with supplemental funding.

But, above all else, the debate around college affordability should not, as I’ve written before, revolve solely around tuition. “When colleges advertise for students, accept millions of dollars in state and federal grants to subsidize it, take checks from students and their parents, and convince them to take out loans to attend, they are making an implicit bargain to provide the students who walk through their doors a better life,” the Third Way report concludes. “The data presented in our mobility metric brings into focus the startling truth that many colleges are simply not fulfilling their end of this bargain.”

||