To understand the importance of school district boundaries, you have to go back to 1974.

By Dwyer Gunn

Demonstrators protesting the segregation of students. (Photo: National Archive/Newsmakers)

Approximately 56 percent of American children today, the majority of them black and Latino, attend a public school that’s classified as “high-poverty.” These schools face profound challenges: Thanks to our education system’s reliance on local tax revenues for funding, schools in poor areas are often desperately under-funded, and struggle to retain teachers and provide kids with the services they need.

Education advocates have won a number of recent high-profile legal battles aimed at making state school funding formulas more fair. But a new report from EdBuild, a non-profit organization dedicated to studying school funding, argues that tweaking school funding formulas isn’t enough; we need to re-think the very boundaries that separate rich kids from poor, and good schools from bad.

“Our wealthy are consigning lower-income students to a lesser caste by cordoning off their wealth and hiding behind the notion of ‘local control,’” the report concludes. “We’ve created and maintained a system of schools segregated by class and bolstered by arbitrary borders that, in effect, serve as the new status quo for separate but unequal.”

To understand the importance of school district boundaries, you have to go back to 1974, when the United States Supreme Court issued a ruling that forever changed education desegregation efforts. Milliken v. Bradley was initially brought to court by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, on behalf of a group of African-American families in Detroit, Michigan. It alleged that the Detroit School Board and the State of Michigan (which was governed at the time by William Milliken) had not only engaged in official acts of racial discrimination, but had, in fact, knowingly pursued a policy agenda that worsened segregation in the city’s schools. When the District Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, a clear message was sent: Government at all levels had indeed worked to perpetuate racial segregation in schools.

“If we’re really going to start attacking this issue of borders in a real way in this country, it’s going to have to go through the courts.”

It wasn’t entirely clear, however, how exactly to go about desegregating Detroit’s schools. By 1974, the population of Detroit (and, thus, its school district) was so predominantly black that meaningful desegregation within the district was simply impossible. So Steven Roth, the District Court judge for the case, ordered the state of Michigan to come up with a plan to desegregate the entire Detroit metro area across school district lines: essentially, to transfer some of Detroit’s black students to surrounding school districts. “School district lines,” Roth wrote, “are simply matters of political convenience and may not be used to deny constitutional rights.”

The surrounding school districts weren’t too thrilled with this plan. Along with the state of Michigan, they soon appealed the desegregation order. In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the neighboring school districts had the right to refuse to take part in the desegregation plan (so long as those districts themselves hadn’t also been found guilty of discriminatory acts).

In other words, Detroit’s wealthy suburbs, and wealthy enclaves around the country, could continue to wall themselves off from neighboring poor areas with impunity. America’s school funding system, meanwhile, has exacerbated the problem by giving wealthy areas further incentives to draw school district boundaries that allow for the concentration of wealth (and those local tax revenues), and the exclusion of low-income families.

“In our opinion, the Milliken ruling basically unraveled Brown [v. Board of Education], and gave lots of authority to school districts locally across the country to draw their own boundaries for any reason,” says EdBuild founder Rebecca Sibilia. “We think that this is actually the lawsuit that created a lot of injustice, in terms of our funding system. And more importantly, it entrenched the reliance on local funding and in that way perpetuated the education inequities.”

Today, the school district border between Detroit and Grosse Point, a wealthy suburb, is among the most segregating district borders in the country. Forty-nine percent of children in Detroit today live in poverty. Just a few miles away, in Grosse Point, only 7 percent of children live in poverty. And Detroit’s not alone: EdBuild’s latest report highlights the 50 most segregating borders in the country.

The child poverty rate in the Birmingham, Alabama, school district, for example, is 49.2 percent. In neighboring school districts, many of which seceded from the Birmingham district, child poverty rates are much lower — 6.2 percent in the Vestavia Hills City School District and 6.5 percent in the Mountain Brook City School District.

Overall, EdBuild found that 3,975 school district borders divide communities with childhood poverty rates that differ by at least 14 percentage points. The majority of the most segregating borders in the U.S. are in the Rust Belt, in places like Ohio and Pennsylvania, although Alabama and New York are big culprits as well. Of the 12 states that draw school district lines along county borders, only one of those states (Alabama) has highly segregated borders.

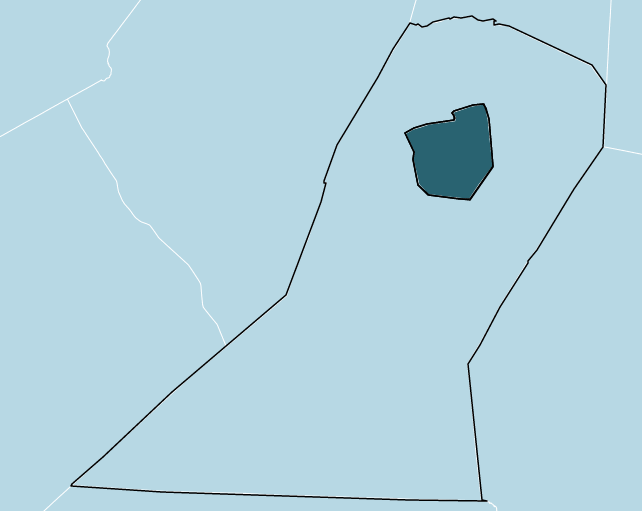

Freehold district. (Map: EdBuild)

Often, these borders, which are not subject to regular review or modification (unlike the borders of Congressional districts), produce collections of districts that are woefully inefficient. Earlier this year, EdBuild produced a report on “island school districts” — particularly wealthy (or poor) districts surrounded by much poorer (or wealthier) districts. Consider, for example, the Freehold Borough district in New Jersey, a tiny school district serving approximately 1,300 kids with a student poverty rate of 31 percent. It’s surrounded on all sides by the Freehold Township School District, where the student poverty rate is only 5 percent and per-pupil education revenues are almost $5,000 higher.

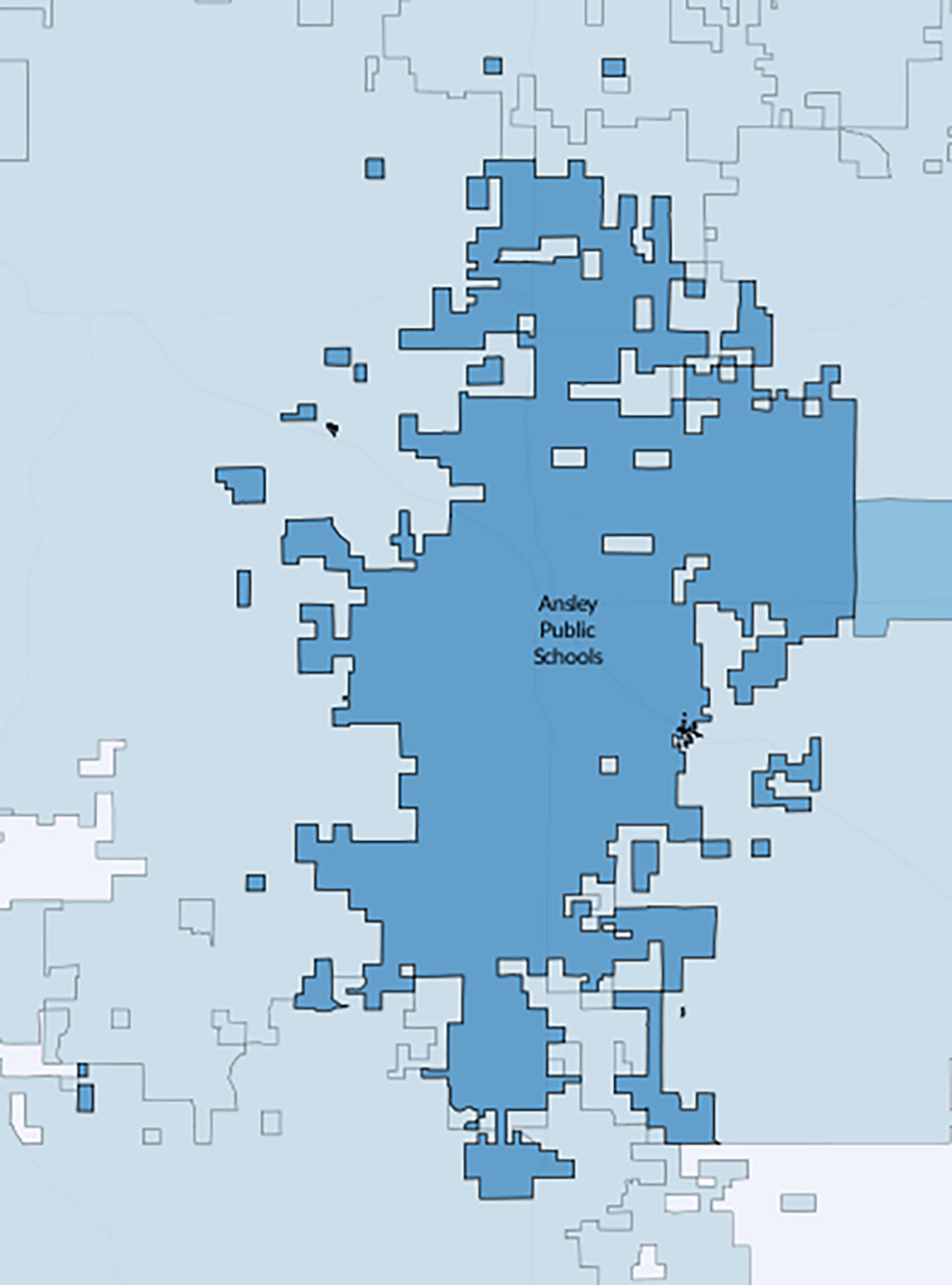

In Nebraska, the Ansley Public School district, with a student poverty rate of 30 percent, has bizarre, non-contiguous islands sprinkled across four different communities, all of which have much lower poverty rates and better education funding. Meanwhile, within the central area of the Ansley district, three wealthier districts have also carved out their own small, non-contiguous islands.

Ansley district. (Map: EdBuild)

These inefficiencies present a real cost to students and taxpayers. In a 2013 report by the Center for American Progress on school district size, researchers concluded that “small, nonremote districts might represent as much as $1 billion in lost annual capacity, by which we mean money that may not have had to be spent if the district was larger.”

So what does all this mean for education inequity in America? Sibilia believes that the solution is two-pronged. Revised school funding formulas that lessen school districts’ reliance on local tax revenues will both make for a fairer distribution of resources and decrease the incentives for wealthy areas to wall themselves off. But the borders themselves also need to be re-drawn, and must be subject to regular impartial review, in much the same way as Congressional district borders, a process Sibilia believes will likely be driven by the judicial action.

“We can make funding less arbitrary, we can update funding models working with the legislature,” Sibilia says. “But if we’re really going to start attacking this issue of borders in a real way in this country, it’s going to have to go through the courts. There’s no legislature that’s going to willingly redraw boundaries.”

In 1848, the then-Secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education Horace Mann wrote: “Education then, beyond all other devices of human origin, is a great equalizer of the conditions of men, — the balance wheel of the social machinery.” Unfortunately, for a great many of the 27 million-plus children in this country who attend high-poverty schools, our education system is the exact opposite — an institution that perpetuates inequalities, rather than erasing them.