Like most other total institutions, prisons are colored by the interactions occupants share with their bureaucratic overlords.

Previous research has suggested that when these relationships buckle amid the drudgery of isolation or the annoyance of constant surveillance, tensions can increase “psychological distress” among inmates. When the relationships are strong, though, they can translate to “less prisoner misconduct” and “less mental health problems,” according to Karin Beijersbergen, a researcher at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement. “In other words, good staff-prisoner relationships are important for the manageability and safety in prisons,” Beijersbergen told Pacific Standard in an email.

Though many scholars focusing on penitentiaries suspect that staff-prisoner relations are molded by institutional architecture, little empirical work has been completed on the topic. Now, a new study led by Beijersbergen and published in Crime & Delinquency has concluded that building styles, floor plans, and other design features do indeed have a significant impact on the way Dutch prisoners perceive their relationships with prison staff.

Beijersbergen and her team visited prisons across the country, making notes of their architectural style, age of construction, and other design features, like unit sizes and numbers of double bunk cells. Then they compared that data to results of a survey among 1,764 inmates housed in one of 32 correctional facilities.*

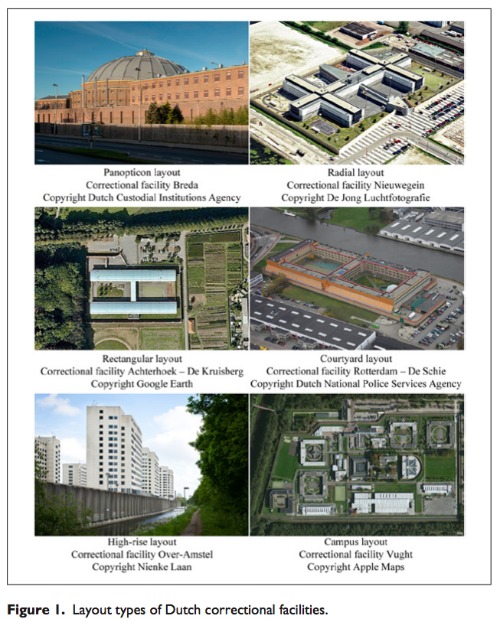

Of the correctional facilities they visited, there were six main styles, each constructed in different time periods, ranging from the late 19th century to the beginning of the 21st:

The authors suspected that the panopticon layout, dreamt up by social reformer Jeremy Bentham in the late 1700s, would be the most detrimental to inmate life. Though categorized as a utopian thinker, Bentham had a strangely dark vision of rehabilitation:

… The panopticon prison consists of a circular structure with a domed roof and cells arranged in tiers on the circumference of the circle. The center of the building contains the “inspection house,” from which the staff are able to watch the prisoners. Originally, this design allowed staff to observe all prisoners of the facility without prisoners knowing whether they were being watched (i.e., seeing without being seen). Although Dutch panopticon prisons were based on Bentham’s idea, a significant change was made, that is, the walls and doors of the cells are solid, so that a complete inspection as envisioned by Bentham is not possible.

The architectural form is regularly name-checked in lofty theoretical papers about political control and surveillance. Many were constructed in the second half of the 1800s in the Netherlands.

The radial layout and its long corridors were also popular during this period and inspired by the “principle of keeping prisoners in solitary confinement.” “Separating prisoners and preventing prisoners from communicating with each other was thought to lead to self-reflection and remorse and, ultimately, to moral elevation,” the authors write. In this setup, cell units are oriented around a “central inspection center.”

Additional prisons were built between 1975 and 1980, and focused more heavily on “rehabilitation and reintegration.” This is when high-rise buildings, with “multiple small stacked pavilions” and “communal living rooms,” came into vogue.**

With a swelling inmate population and “several successful escapes,” the Dutch built courtyard-style prisons and more radial structures between 1985 and 2005. Two other styles, campus and rectangular layouts, are not “clearly linked to a specific construction period and/or penal philosophy.”

After controlling for age, ethnicity, intimate relationships at the time of arrest, education level, personality traits, criminal histories, and officer-to-inmate ratios, the authors discovered that their hunch was correct. If the prisoners were housed in leaky dungeon-like panopticons, they tended to feel more estranged from guards. But if they were enjoying campus-style living arrangements or apartment-style high-rises, they perceived the relationships as more supportive.

… Prisoners in panopticon layouts were least positive about their relationships with officers. Prisoners in radial, courtyard, rectangular, and high-rise layouts had an increasingly positive judgment about officer-prisoner relationships. When compared with prisoners in panopticon layouts, prisoners in campus layouts were most positive about these relationships. …

The analysis also turned up a significant relationship between the perceptions and two more specific variables, age of construction and double bunks. “Prisoners experienced their relationships with officers more positively in newer units and in units with a lower percentage of double cells,” the authors write. “Old units and high levels of double bunking are especially present in panopticon layouts.” Double bunking might mean less individual attention from prison staff, the authors note.

Are there other reasons the panopticons sow animosity and the open alternatives breed positivity? The authors speculate:

… First, panopticon prisons were constructed with a focus on prisoner surveillance, as staff could observe all prisoners of the facility from the center of the building. This physical distance between staff and prisoners is likely to result in more detached and distant officer-prisoner relationships. Other characteristics of the panopticon may also contribute to distant relationships: (a) the large size and scale of the panopticon may increase anonymity and result in more impersonal and less frequent officer-prisoner interactions and (b) the old age of panopticon prisons with their gloomy appearance and less up-to-date prison conditions may negatively affect the atmosphere in prison and negatively influence officer-prisoner interactions. …

… Dutch high-rise prisons, consisting of small pavilions with a “homely” atmosphere and emphasizing communal activities and a humane treatment of prisoners, aimed to rehabilitate prisoners. The design was expected to encourage close staff-prisoner relationships. Dutch campus prisons are also characterized by small living units, which may facilitate more and more personal staff-prisoner interactions.

Clearer lines of sight on campuses and in high-rises, which the authors note has been associated with positive interactions in past studies, may also put the guards themselves at ease and encourage more friendly interaction. Conversation is more convenient when you’re not anxiously awaiting a potential threat to pop out from the periphery of your security purview.

Can any of these results inform the staunchly rigid and notoriously drab American prison system? Could bucolic open campuses even work in the United States? A 2010 Crime & Delinquency paper that analyzed misconduct in Texas prisons found that campus architecture didn’t have any direct effect on violence, so more open layouts probably wouldn’t result in any grave unforeseen effects. The authors did discover a positive relationship between campus-style prisons and minor property infractions, but this could also just be the result of broader surveillance.

Major shifts here won’t be that easy, given the larger American penal culture and its long-running traditions of torture, discipline, over-crowding, and prison gangs. “[T]he Netherlands is still regarded as having a relatively mild prison policy,” Beijersbergen says. “Staff-prisoner relationships are generally characterized as informal and supportive, levels of misbehavior and violence are much lower compared to the U.S., and gangs are not common in Dutch prison. So, before building different American prisons, I would suggest additional research among American prisons. I do have to say though, that research on American ‘new generation prisons’ (which are also characterized as semi-autonomous pods, with small units and good visual access) is promising.”

Beijersbergen believes more prison architects need to understand how their buildings can affect the lives of their residents, instead of focusing solely on aesthetics or security. The more progressive philosophy has resonated with some Americans. Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) has lobbied the American Institute of Architects for an ethical amendment that would restrict its members from drawing blueprints for solitary confinement cells. Members of ADPSR’s larger campaign signed a pledge refusing to work on prison projects of any kind. Their theory:

Foucault believed that disciplinary systems, and prisons in particular (with the Panopticon as the ideal type) were social failures. He considered that the way disciplinary systems crush individuality and individual freedom is antithetical to positive social goals such as rehabilitation and peaceful coexistence. He also saw the inherent cruelty of prison buildings for what they are – spaces where state agents, dedicated to maintaining state power, exact revenge and enforce discipline on those who fail to abide by the system. Given the overwhelming failure of prisons to reduce crime and the endless catalogue of abuses committed within prisons, ADPSR agrees with Foucault. It is time for architects to find new means of building a just society, and new buildings for a better set of institutions. The disciplinary model of the prison/Panopticon is a failure.

Beijersbergen doesn’t believe there’s a one-size-fits-all-inmates approach, but if prison architects wanted some ideal inspiration, they could look to Norway’s Bastøy prison, on Bastøy island. Though Bastøy’s facilities are slightly reminiscent of a Nantucket sleep-away camp, the prison supports a phenomenal recidivism rate of 16 percent, far below Europe’s average. “There is a clear focus on human relations,” Beijersbergen says. “Good and constructive staff-prisoner relationships are an essential part of their philosophy. In addition, by giving prisoners more autonomy and responsibility, you might prepare them better for life after detention.” Austria’s Leoben prison has a similarly compelling setup.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6V_QiOa2JoThough Beijersbergen doesn’t expect that Bastøy will ever become a viable option somewhere like the U.S., she hopes it will. “I think it might be a nice example of a humane and decent prison that can also be effective (with respect to re-offending after release),” she says. “However, I do not think that this kind of prison is suitable for all prisoners.”

*UPDATE — June 20, 2014: We originally wrote that the data was from national inmate surveys. The data was from a representative survey of 1,764 inmates, conducted as part of a long-term study in the Netherlands called the Prison Project.

**UPDATE — June 20, 2014: We originally described the building period between 1975 and 1980 as a “boom.” A few facilities were built, but it was not a boom.