Until policymakers recognize how central gender is to every security policy and issue, we will continue to live in an unsafe world.

By Elizabeth Weingarten & Valerie Hudson

Portrait of Assembly and Repairs Department senior supervisor Eloise J. Ellis as she stands near the tail of a Navy plane at Naval Air Station, Corpus Christi, Texas, in August of 1942. (Photo: Howard R. Hollem/Getty Images)

During the second presidential debate, moderator Anderson Cooper pressed President-elect Donald Trump to respond to the tape that recorded him boasting about sexual assault.

Trump countered by dismissing his language as insignificant compared to, say, “ISIS chopping off heads…. Yes, I’m very embarrassed by [the tape] … but it’s locker room talk. I will knock the hell out of ISIS.”

Trump thought he was changing the subject, but he wasn’t. That is, these two issues — the rise of a murderous regime such as ISIS and the normalization of sexual assault — are inextricably linked. In fact, as New America President Anne-Marie Slaughter and Elizabeth Weingarten wrote recently, ISIS exploits and exacerbates gender inequality to recruit and retain its members. It could not do this effectively unless gender inequality was already accepted within the culture. Research by Valerie M. Hudson shows that whether a country is secure, peaceful, and prosperous has more to do with the way it treats its women than any other factor.

Ignoring that connection is a type of policy myopia, then, and while it would be easy to blame Trump for introducing it into national security policymaking and discourse, the belief that gender equality is secondary or irrelevant to issues of “hard security” has long been an often unspoken yet central tenet of United States national security policymaking, even 16 years after the United Nations Security Council passed its first landmark resolution that highlighted conflict’s disproportionate effect on women and the key role that women play in national security and peace-building. Women, for instance, played negligible roles as mediators during the most recent Syrian and Afghanistan peace talks, despite research that links sustainable peace deals with women’s participation. What’s more, gender was an afterthought to our intervention in Iraq. Even after U.S. forces toppled Saddam Hussein, policymakers failed to integrate gender considerations into the larger plan for establishing Iraqi stability. We can see that reflected in the latest troop withdrawal, where the U.S. government executed a plan with minimal consideration of how it would affect women’s rights in the country. It is sad but true that Iraqi women are far less secure in the wake of the U.S. intervention than they were before it, partly because that subject simply wasn’t part of the discussion.

At New America, we recently investigated this disconnect, asking national security and foreign policy elites first how much they thought about gender when formulating policy. The answer was that most of them thought about it very little. Many respondents conflated thinking about a policy’s gendered effects (in other words, how a policy might impact men or women differently) with gender representation around the decision-making table. In other words, if there was a female face at the table, even one, that sufficed in terms of consideration of gender in the discussion. In fact, these are two distinct, and often unrelated, issues: While presence of women around the policymaking table is important, they cannot create a gender-sensitive policy alone. All around the table must be involved in such an effort.

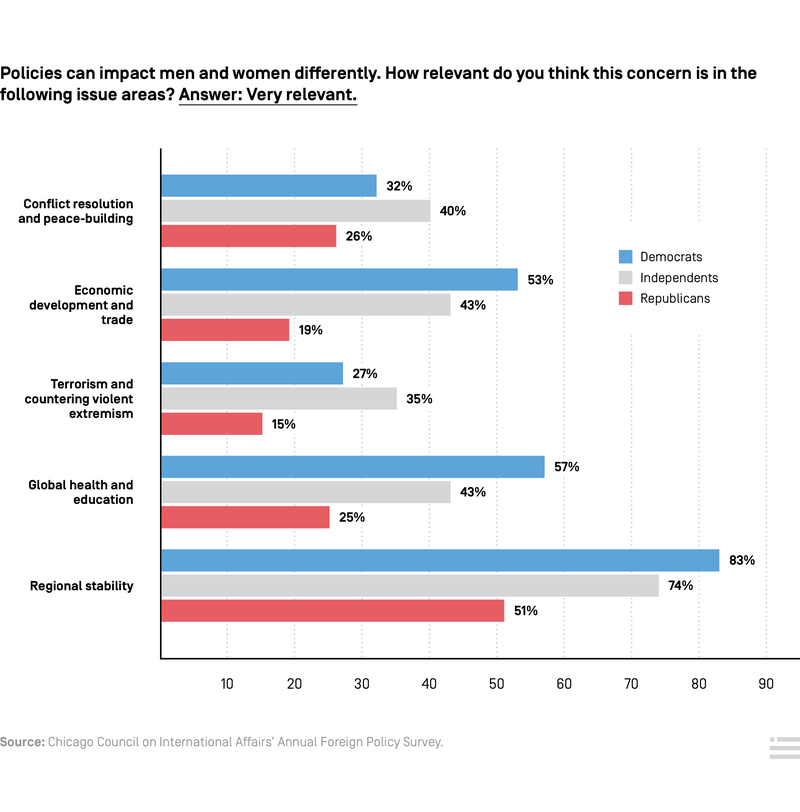

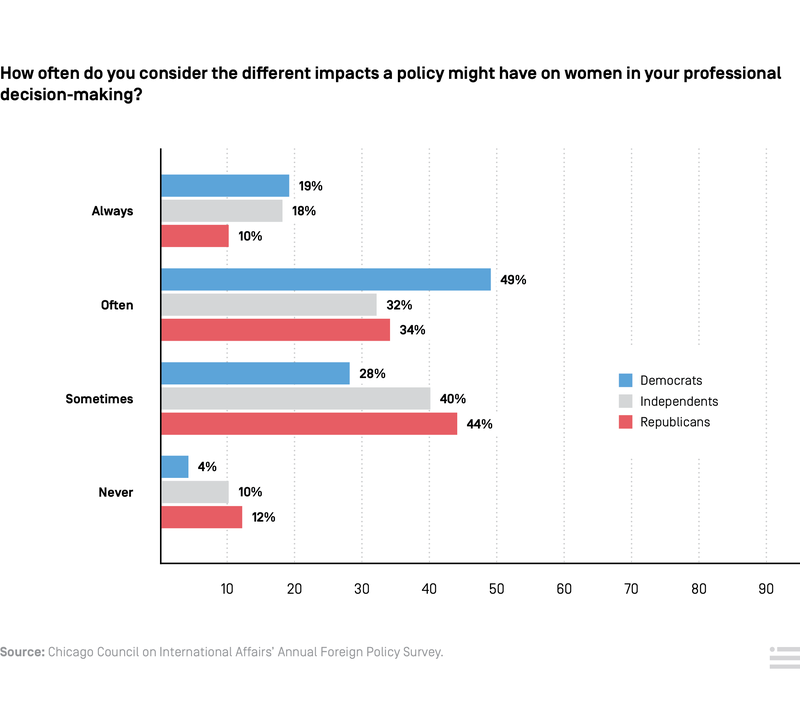

According to New America’s research — research produced in collaboration with the Chicago Council on International Affairs’ annual survey of policy elites and influencers — this disconnect transcends partisan divides. Only 26 percent of Republicans and 32 percent of Democrats thought gender was relevant to policy issues associated with conflict resolution and peace-building, and just 15 percent of Republicans and 27 percent of Democrats thought it was relevant to terrorism and extremism. A paltry 10 percent of Republicans and 19 percent of Democrats said that they always considered whether a policy would affect men or women differently.

Part of the reason that policymakers fail to consider gender may be that “gender” is often misunderstood as a synonym for women, when it actually describes men, women, and the dynamic between them. It creates the first political order within a society, one that influences how we relate to others, and how we govern ourselves. That means that the people fighting for gender equity aren’t advocating for some special interest group that will only affect a sliver of the population. The male/female relationship is created and sustained by all within the society. And yet, the more that policymakers, particularly male ones, define gender as “women’s stuff,” the more they miss the real security implications of a hierarchical gender order.

Here’s one consequence of that oversight: Post-conflict stabilization is simply unobtainable without assuring the security — and including the voices — of women. The situation of women is a key marker of whether a society is descending into chaos, morphing into a breeding ground for extremist organizations. To give one recent example, ignoring what would happen to women in the wake of U.S. and allied intervention was more than an oversight — it was a missed opportunity to counter the rise of ISIS in countries like Libya and Iraq.

In these situations, policymakers didn’t necessarily ignore gender because they didn’t care, but rather because the frameworks they used to guide those interventions, like the Responsibility to Protect policy and the Atrocities Prevention Board formula, lacked a meaningful gender analysis of the root causes of instability and long-term effects of interventions. These policy frameworks constrained thinking and provided fewer openings to integrate gender-based indicators and analysis into strategy.

Without that analysis, the subsequent military intervention in Libya included a shift of power to groups that subordinated women and stripped away women’s rights. This contributed to an increase in rates of violence against women and to broader regional instability and insecurity, easing the way for ISIS to start recruiting and building out statehood there. It is no coincidence that these groups immediately targeted women human rights defenders for assassination; these women are real obstacles to their plans, and offer real alternatives to their power.

Had policymakers baked a consideration of what would happen to women in the absence of a government, or with a weak government, into these frameworks, they might have been able to prevent some of these disastrous consequences. For instance, they could have mandated that intelligence officers gather metrics on gender-focused indicators that we know can be early warning signs for societal instability — like constraints on women’s mobility, increased levels of violence against women, and the decline of girls’ education rates due to increasing levels of child marriage.

They also could have pushed for funding to protect the female activists and advocates who too often become targets in post-conflict environments, potentially arming and training their male relatives to become bodyguards. If this was part of military planning and a key element for the division of stability operations within the Pentagon, it would be easier to consider gender impacts in those harried moments when officials are forced to make fast choices about how best to enter an urgent conflict.

Or, how to engage in a region where it looks like the worst is over. Hudson will argue in her forthcoming book, The First Political Order, that, when centralized governments are undermined, even if one believes the government to be odious, what she calls male-bonded kin groups reassert themselves as the foundation of societal order. One of the first things such groups do is reassert a clear hierarchy between men and women, legitimizing their own power by suppressing women, and, in some cases, strengthening and creating their bonds by abusing and hurting women.

Thus, women’s rights and women’s security are typically the first thing to go when the old government goes, enabling men to create legitimacy in the minds of other men. Ripping the Qaddafi regime off the Libyan people left only anarchy, fear, and a resurgence of patrilineality as citizens — even women — sought security through the male-bonded kin group mechanism. The same process played out in Iraq. And it could happen again, depending on how Trump decides to “bomb the shit out of ISIS.” It’s one reason that policymakers must watch all of the areas that have recently been liberated from ISIS’s grip—they are fertile ground for those male-bonded kin groups to assert their power through subordinating women, with all the negative ramifications for stability that subordination entails.

We’ve found that, in some circles, being gender blind, or gender neutral, is seen as virtuous—as if thinking about differences in gender is akin to introducing prejudice or bias. When Ivanka Trump was trying to paint her father in a more positive light, she gushed that he was “race-blind” and “gender neutral.” She’s not alone in employing such language: In our study, many men explained the fact that they see the person, not the gender, by recalling their childhood surrounded by strong female role models — citing their mothers as part of the reason that now they are “gender blind.”

It’s one thing to be gender blind or neutral when it comes to not stereotyping people based on their gender, and not making decisions to preference a gender based only on stereotypes. But it’s another thing to ignore gender differences in how people interact with the world, the constraints that they face based on gender, and how different policies — such as a “humanitarian intervention” — might affect their lives. That’s a lot like being “color-blind,” but denying that racial inequalities can influence how policies and systems are constructed, and how people of different races interact with those frameworks. Many of the respondents in our study considered certain policy subjects to simply be irrelevant to gender — like weapons defense, economics, trade, and arms treaties. But they weren’t always certain about how and why they held such beliefs. “The consequence of policy is often the same for men and women,” one respondent said, before adding: “Hearing myself say that gives me pause. I have no idea what that conclusion is actually based on — am I just regurgitating the company line?”

The problem with blind spots is that you end up blindsided by unintended consequences. Until we recognize how central it is to every security policy and issue, we will continue to live in a world that is less safe — for both women and men.

This story originally appeared in New America’s digital magazine, New America Weekly, a Pacific Standard partner site. Sign up to get New America Weekly delivered to your inbox, and follow @NewAmerica on Twitter.