A decades-long journalism career at Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, and Beliefnet left Steven Waldman sure of one thing: The collapse of local newspapers would be detrimental to small communities. Without quality reporting, he says, it would be “impossible” for Americans to hold power accountable.

“Communities just don’t function well and families don’t get the services they need when there’s not good local journalism,” Waldman says.

In 1994, Waldman left Newsweek and joined the Corporation for National and Community Service, which runs the job-training organization AmeriCorps. Later, he served as a senior adviser with the Federal Communications Commission, where he published a 2011 report on the disappearance of local accountability reporting. His experiences at the FCC taught him that a lack of boots-on-the-ground reporting was the biggest problem with modern media. When outlets focused more on generating advertising, the breadth and depth of coverage went down. If local reporters were not visible in the community, newspaper readers felt like they couldn’t trust the outlets.

“We had gotten so focused on new ways of reaching audience that we stopped emphasizing a core element: If we don’t have people on the ground, we’re not going to properly service Americans,” Waldman says.

HOW NEWSROOMS ARE TRYING TO MAKE THE MEDIA GREAT AGAIN: Public opinion of the media is at an all-time low. How do outlets regain Americans’ trust?

In 2016, Waldman and Charles Sennott created Report for America, a new journalism training corps blending the traditional job-education organization with a model for sustainable reporting. The emphasis is on hiring a diverse group of journalists to cover underrepresented regions of the United States. So far, Waldman says, the program has drawn interest from hundreds of reporters and 85 local news organizations looking to host entry-level reporters.

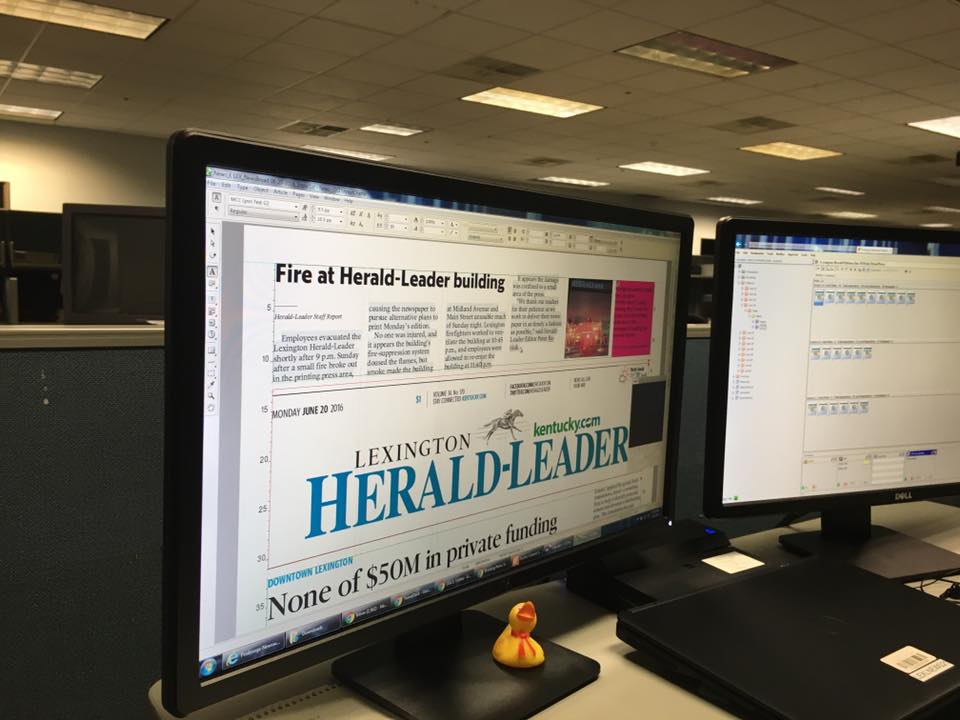

Report for America’s pilot program, which launched last month, placed three early-career reporters in Appalachian newsrooms, at West Virginia Public Broadcasting, the Lexington Herald-Leader, and the Charleston Gazette-Mail. The program includes mentorship and training programs, and just like their cohorts in urban newsrooms, the journalists are expected to file stories regularly and will receive a salary equivalent to other entry-level reporters.

Report for America’s first class consists of three reporters familiar with Appalachia: Caity Coyne, a recent graduate of West Virginia University reporting for the Charleston Gazette-Mail; Molly Born, a West Virginia native reporting for West Virginia Public Broadcasting; and Will Wright, a recent graduate of the University of Kentucky reporting for the Lexington Herald-Leader.

The GroundTruth Project, Report for America’s parent company, will pay half their salaries. As a non-profit media organization, GroundTruth provides funding for reporters at a number of media organizations to complete independent projects based on social justice and globalization.

Another quarter of the Report for America fellow salaries will come from their host media outlet. Anonymous donors from the regions hosting new reporters make up the rest, with money funneled through Report for America to avoid bias or slant in reporting.

Waldman believes this program is the GroundTruth’s chance to do something about the double-edged sword in journalism—”the crisis of the pocketbook and the crisis of the soul.” Lack of funding has led media outlets to slash jobs. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center report, there were 41,400 newspaper reporters and editors in the U.S. in 2015—down almost 38 percent from 2005.

For those remaining, there’s what Waldman calls the “crisis of the soul,” where well-intentioned reporters are stretched too thin—and sometimes too engaged in mandatory clickbait—to pursue deeper investigations into the issues that affect their audience.

If the funding can fix some of the “crisis of the pocketbook,” then the next step is fixing the relationship between storytellers and their subjects. Building foundations of trust between reporters and their audiences is essential. Grant, the vice president of RFA, says that reporters will also engage in other activities within the community to show who they are independent of being journalists.

“Reporting is really so much about people, and that is too often forgotten,” Grant says.

Wright, the Report for America fellow at the Lexington Herald-Leader, sees this as an opportunity to cover problems within a community he has grown to love. After graduating from college, Wright hiked the Appalachian Trail, where he developed an intimate knowledge of the issues locals face.

Some feel like their issues are portrayed inaccurately by national media outlets, which lack historical context of the region and don’t understand some of the long-term problems they face. Recent coverage of Appalachia from national outlets has focused on the opioid epidemic.

Meanwhile, Report for America fellows have identified other real problems locals face. Wright’s first story as a reporter in the Pikesville bureau was a piece on water shutting off for 1,000 residents, and the ensuing chaos—a story that only a local journalist would be able to tell.

“We’re going in and finding problems within specific communities, looking at them with a lens of solution and how does it fit into the region as a whole,” Wright says.

Building trust with locals is important to quality journalism. During their training at West Virginia University, the first three fellows have already discussed in-depth how to build trust with the communities they cover. They’ll also have support from their newsrooms. Jesse Wright (no relation to Will Wright), the news director at West Virginia Public Broadcasting, says that his newsroom already has what he calls a peer support system for new reporters, to teach cultural understanding of the region.

WHY THE MEDIA REFUSES TO UNDERSTAND ANTIFA: While establishment pundits fret over civility, the antifascist movement in America is working for peace.

Fellows are also required to serve the community independent of their roles as journalists. This could mean volunteering with nearby schools, gyms, and community centers.

“The biggest way to gain trust with people is to do a good job,” Wright says. “While I think there is some distrust, I think there’s a lot of people who are happy to see coverage of their communities.”

Applications are now open for the rest of the 2018 Report for America Corps. Prospective fellows can apply to work at one of nine newsrooms by March 23rd, including the Dallas Morning News, Macon Telegraph, and Chicago Sun-Times. Each newsroom has identified niches for a reporting fellow—anything from poverty in neglected neighborhoods (in Chicago, that means the South and West Sides) to post-natural disaster coverage.

While the current cohort has ties to the area they’re reporting from, the organization plans to work with people not native to their newsrooms’ communities.

“There’s value both in terms of the reporters and what they can learn from each other,” Waldman says. “The person who’s from that area will have great insight into the area and its problems. The person who’s from outside will have a fresh eye and be able to see things that sometimes you can’t see when you’re in the middle of that.”

All four agree: In the end, good journalism is all about nitty-gritty local reporting. Report for America isn’t simply an opportunity for young reporters to build their portfolios. “It’s an improving journalism in communities program,” Waldman says.